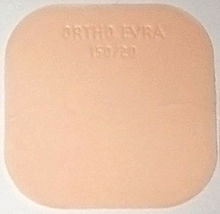

Back لصاقة جلدية Arabic Transdermales Pflaster German Έμπλαστρο Greek Parche transdérmico Spanish Timbre transdermique French מדבקה מלעורית HE Plester transdermal ID Cerotto transdermico Italian 経皮吸収パッチ Japanese 경피 패치 Korean

A transdermal patch is a medicated adhesive patch that is placed on the skin to deliver a specific dose of medication through the skin and into the bloodstream. An advantage of a transdermal drug delivery route over other types of medication delivery (such as oral, topical, intravenous, or intramuscular) is that the patch provides a controlled release of the medication into the patient, usually through either a porous membrane covering a reservoir of medication or through body heat melting thin layers of medication embedded in the adhesive. The main disadvantage to transdermal delivery systems stems from the fact that the skin is a very effective barrier; as a result, only medications whose molecules are small enough to penetrate the skin can be delivered by this method. The first commercially available prescription patch was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in December 1979. These patches administered scopolamine for motion sickness.[2][3][4][5]

In order to overcome restriction from the skin, researchers have developed microneedle transdermal patches (MNPs), which consist of an array of microneedles, which allows a more versatile range of compounds or molecules to be passed through the skin without having to micronize the medication beforehand. MNPs offer the advantage of controlled release of medication and simple application without medical professional assistance required.[6] With advanced MNPs technology, drug delivery can be specified for local usage, for example skin whitener[7] MNPs that are applied to the face. Many types of MNPs have been developed to penetrate tissues other than skin, such as internal tissues of the mouth and digestive tract. These promote faster and more direct delivery of the molecule to the targeted area.

- ^ McConville, Aaron; Hegarty, Catherine; Davis, James (June 8, 2018). "Mini-Review: Assessing the Potential Impact of Microneedle Technologies on Home Healthcare Applications". Medicines. 5 (2): 50. doi:10.3390/medicines5020050. ISSN 2305-6320. PMC 6023334. PMID 29890643.

- ^ VEERABADRAN, NALINKANTH G.; PRICE, RONALD R.; LVOV, YURI M. (April 2007). "Clay Nanotubes for Encapsulation and Sustained Release of Drugs". Nano. 02 (2): 115–120. doi:10.1142/s1793292007000441. ISSN 1793-2920.

- ^ "FDA approves rolapitant to prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea". The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2015. doi:10.1211/pj.2015.20069288. ISSN 2053-6186.

- ^ Segal, Marian. "Patches, Pumps and Timed Release: New Ways to Deliver Drugs". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on February 10, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ "FDA approves scopolamine patch to prevent peri-operative nausea". Food and Drug Administration. November 10, 1997. Archived from the original on December 19, 2006. Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- ^ Lee, Jeong Woo; Prausnitz, Mark R. (May 7, 2018). "Drug delivery using microneedle patches: not just for skin". Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 15 (6): 541–543. doi:10.1080/17425247.2018.1471059. ISSN 1742-5247. PMID 29708770. S2CID 14038378.

- ^ Li, Junwei; Zeng, Mingtao; Shan, Hu; Tong, Chunyi (August 23, 2017). "Microneedle Patches as Drug and Vaccine Delivery Platform". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 24 (22): 2413–2422. doi:10.2174/0929867324666170526124053. ISSN 0929-8673. PMID 28552053.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search