Back اعتلال دماغي إسفنجي قابل للانتقال Arabic Encefalopatía esponxiforme transmisible AST Прыёнавыя хваробы Byelorussian Transmisivna spongiformna encefalopatija BS Encefalopatia espongiforme transmissible Catalan Transmisivní spongiformní encefalopatie Czech TSE Danish Transmissible spongiforme Enzephalopathie German Encefalopatía espongiforme transmisible Spanish انسفالوپاتیهای اسفنجی شکل Persian

This article needs attention from an expert in Medicine. The specific problem is: "Cause" section is in fairly bad shape with undue weight. (January 2022) |

| Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Prion disease |

| |

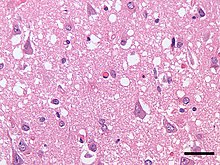

| Micrograph showing spongiform degeneration (vacuoles that appear as holes in tissue sections) in the cerebral cortex of a patient who had died of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. H&E stain, scale bar = 30 microns (0.03 mm). | |

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

| Symptoms | Dementia, seizures, tremors, insomnia, psychosis, delirium, confusion |

| Usual onset | Months to decades |

| Types | Bovine spongiform encephalopathy, Fatal familial insomnia, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, kuru, scrapie, variably protease-sensitive prionopathy, chronic wasting disease, Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome, feline spongiform encephalopathy, transmissible mink encephalopathy, exotic ungulate encephalopathy |

| Causes | Prion |

| Risk factors | Contact with infected fluids, ingestion of infected flesh, having one or two parents that have the disease (in case of fatal familial insomnia) |

| Diagnostic method | Currently there is no way to reliably detect prions except at post-mortem |

| Prevention | Varies |

| Treatment | Palliative care |

| Prognosis | Invariably fatal |

| Frequency | Rare |

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), also known as prion diseases,[1] are a group of progressive, incurable, and fatal conditions that are associated with prions and affect the brain and nervous system of many animals, including humans, cattle, and sheep. According to the most widespread hypothesis, they are transmitted by prions, though some other data suggest an involvement of a Spiroplasma infection.[2] Mental and physical abilities deteriorate and many tiny holes appear in the cortex causing it to appear like a sponge when brain tissue obtained at autopsy is examined under a microscope. The disorders cause impairment of brain function which may result in memory loss, personality changes, and abnormal or impaired movement which worsen over time.[3]

TSEs of humans include Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker syndrome, fatal familial insomnia, and kuru, as well as the recently discovered variably protease-sensitive prionopathy and familial spongiform encephalopathy. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease itself has four main forms, the sporadic (sCJD), the hereditary/familial (fCJD), the iatrogenic (iCJD) and the variant form (vCJD). These conditions form a spectrum of diseases with overlapping signs and symptoms.

TSEs in non-human mammals include scrapie in sheep, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle – popularly known as "mad cow disease" – and chronic wasting disease (CWD) in deer and elk. The variant form of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in humans is caused by exposure to bovine spongiform encephalopathy prions.[4][5][6]

Unlike other kinds of infectious disease, which are spread by agents with a DNA or RNA genome (such as virus or bacteria), the infectious agent in TSEs is believed to be a prion, thus being composed solely of protein material. Misfolded prion proteins carry the disease between individuals and cause deterioration of the brain. TSEs are unique diseases in that their aetiology may be genetic, sporadic, or infectious via ingestion of infected foodstuffs and via iatrogenic means (e.g., blood transfusion).[7] Most TSEs are sporadic and occur in an animal with no prion protein mutation. Inherited TSE occurs in animals carrying a rare mutant prion allele, which expresses prion proteins that contort by themselves into the disease-causing conformation. Transmission occurs when healthy animals consume tainted tissues from others with the disease. In the 1980s and 1990s, bovine spongiform encephalopathy spread in cattle in an epidemic fashion. This occurred because cattle were fed the processed remains of other cattle, a practice now banned in many countries. In turn, consumption (by humans) of bovine-derived foodstuff which contained prion-contaminated tissues resulted in an outbreak of the variant form of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in the 1990s and 2000s.[8]

Prions cannot be transmitted through the air, through touching, or most other forms of casual contact. However, they may be transmitted through contact with infected tissue, body fluids, or contaminated medical instruments. Normal sterilization procedures such as boiling or irradiating materials fail to render prions non-infective. However, treatment with strong, almost undiluted bleach and/or sodium hydroxide, or heating to a minimum of 134 °C, does destroy prions.[9]

- ^ "Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ Bastian FO, Sanders DE, Forbes WA, Hagius SD, Walker JV, Henk WG, Enright FM, Elzer PH (2007). "Spiroplasma spp. from transmissible spongiform encephalopathy brains or ticks induce spongiform encephalopathy in ruminants". Journal of Medical Microbiology. 56 (9): 1235–1242. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.47159-0. PMID 17761489.

- ^ Chesebro, Bruce (2003-06-01). "Introduction to the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies or prion diseases". British Medical Bulletin. 66 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1093/bmb/66.1.1. ISSN 1471-8391. PMID 14522845.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2017-04-25. February 2012. Archived from the original on December 20, 2002.

- ^ "Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease > Relationship with BSE (Mad Cow Disease)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2017-04-25. 10 February 2015.

- ^ Collinge, J; Sidle, KC; Meads, J; Ironside, J; Hill, AF (October 24, 1996). "Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of 'new variant' CJD". Nature. 383 (6602): 685–690. Bibcode:1996Natur.383..685C. doi:10.1038/383685a0. PMID 8878476. S2CID 4355186.

- ^ Brown P, Preece M, Brandel JP, Sato T, McShane L, Zerr I, Fletcher A, Will RG, Pocchiari M, Cashman NR, d'Aignaux JH, Cervenakova L, Fradkin J, Schonberger LB, Collins SJ (2000). "Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease at the millennium". Neurology. 55 (8): 1075–81. doi:10.1212/WNL.55.8.1075. PMID 11071481. S2CID 25292433.

- ^ Colle, JG; Bradley, R; Libersky, PP (2006). "Variant CJD (vCJD) and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE): 10 and 20 years on: part 2". Folia Neuropatholica. 44 (2): 102–110. PMID 16823692.

- ^ "Prion Disinfection Options - Biosafety & Occupational Health". University of Minnesota. 17 November 2017.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search