Back رجفان بطيني Arabic Фібрыляцыя страўнічкаў Byelorussian Komorska fibrilacija BS Fibril·lació ventricular Catalan Fibrilace komor Czech Kammerflimmern German Κοιλιακή μαρμαρυγή Greek Fibrilación ventricular Spanish Vatsakeste virvendus Estonian Fibrilazio bentrikular Basque

| Ventricular fibrillation | |

|---|---|

| |

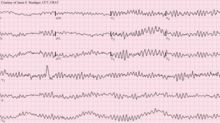

| 12-lead ECG showing ventricular fibrillation | |

| Specialty | Cardiology, Emergency Medicine |

| Symptoms | Cardiac arrest with loss of consciousness and no pulse[1] |

| Causes | Coronary heart disease (including myocardial infarction), valvular heart disease, cardiomyopathy, Brugada syndrome, electric shock, long QT syndrome, intracranial hemorrhage[2][1] |

| Diagnostic method | Electrocardiogram[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Torsades de pointes[1] |

| Treatment | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) with defibrillation[3] |

| Prognosis | Survival rate 17% (out of hospital), 46% (in hospital)[4][5][1] |

| Frequency | ~10% of people in cardiac arrest[1] |

Ventricular fibrillation (V-fib or VF) is an abnormal heart rhythm in which the ventricles of the heart quiver.[2] It is due to disorganized electrical activity.[2] Ventricular fibrillation results in cardiac arrest with loss of consciousness and no pulse.[1] This is followed by sudden cardiac death in the absence of treatment.[2] Ventricular fibrillation is initially found in about 10% of people with cardiac arrest.[1]

Ventricular fibrillation can occur due to coronary heart disease, valvular heart disease, cardiomyopathy, Brugada syndrome, long QT syndrome, electric shock, or intracranial hemorrhage.[2][1][6] Diagnosis is by an electrocardiogram (ECG) showing irregular unformed QRS complexes without any clear P waves.[1] An important differential diagnosis is torsades de pointes.[1]

Treatment is with cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and defibrillation.[3] Biphasic defibrillation may be better than monophasic.[3] The medication epinephrine or amiodarone may be given if initial treatments are not effective.[1] Rates of survival among those who are out of hospital when the arrhythmia is detected is about 17% while in hospital it is about 46%.[4][1]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Baldzizhar, A; Manuylova, E; Marchenko, R; Kryvalap, Y; Carey, MG (September 2016). "Ventricular Tachycardias: Characteristics and Management". Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America. 28 (3): 317–29. doi:10.1016/j.cnc.2016.04.004. PMID 27484660.

- ^ a b c d e "Types of Arrhythmia". NHLBI. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Neumar, RW; Shuster, M; Callaway, CW; Gent, LM; Atkins, DL; Bhanji, F; Brooks, SC; de Caen, AR; Donnino, MW; Ferrer, JM; Kleinman, ME; Kronick, SL; Lavonas, EJ; Link, MS; Mancini, ME; Morrison, LJ; O'Connor, RE; Samson, RA; Schexnayder, SM; Singletary, EM; Sinz, EH; Travers, AH; Wyckoff, MH; Hazinski, MF (3 November 2015). "Part 1: Executive Summary: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S315-67. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000252. PMID 26472989.

In the appendix

- ^ a b Berdowski, J; Berg, RA; Tijssen, JG; Koster, RW (November 2010). "Global incidences of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and survival rates: Systematic review of 67 prospective studies". Resuscitation. 81 (11): 1479–87. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.006. PMID 20828914.

- ^ Bougouin, W.; Marijon, E.; Puymirat, E.; Defaye, P.; Celermajer, D. S.; Le Heuzey, J.; Boveda, S.; Kacet, S.; Mabo, P.; Barnay, C.; Da Costa, A.; Deharo, J.; Daubert, J.; Ferrières, J.; Simon, T.; Danchin, N. (2013). "Incidence of sudden cardiac death after ventricular fibrillation complicating acute myocardial infarction: a 5-year cause-of-death analysis of the FAST-MI 2005 registry". European Heart Journal. 35 (2): 116–122. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht453. PMID 24258072.

- ^ Barash, Paul G. (2009). Clinical Anesthesia. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 168. ISBN 9780781787635. Archived from the original on 2017-08-08.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search