Back سطح الماء الجوفي Arabic Hladina podzemní vody Czech Grundvandsspejl Danish Grundwasserspiegel German Nivel freático Spanish سطح ایستابی Persian Niveau piézométrique French Nivo idwostatik HT Muka air tanah ID 지하수위 Korean

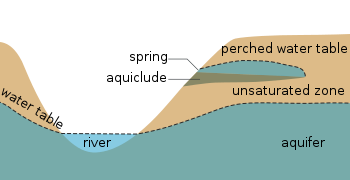

The water table is the upper surface of the phreatic zone or zone of saturation. The zone of saturation is where the pores and fractures of the ground are saturated with groundwater,[1] which may be fresh, saline, or brackish, depending on the locality. It can also be simply explained as the depth below which the ground is saturated. The portion above the water table is the vadose zone. It may be visualized as the "surface" of the subsurface materials that are saturated with groundwater in a given vicinity.[2]

In coarse soils, the water table settles at the surface where the water pressure head is equal to the atmospheric pressure (where gauge pressure = 0). In soils where capillary action is strong, the water table is pulled upward, forming a capillary fringe.

The groundwater may be from precipitation or from more distant groundwater flowing into the aquifer. In areas with sufficient precipitation, water infiltrates through pore spaces in the soil, passing through the unsaturated zone. At increasing depths, water fills in more of the pore spaces in the soils, until a zone of saturation is reached. Below the water table, in the zone of saturation, layers of permeable rock that yield groundwater are called aquifers. In less permeable soils, such as tight bedrock formations and historic lakebed deposits, the water table may be more difficult to define.

“Water table” and “water level” are not synonymous. If a deeper aquifer has a lower permeable unit that confines the upward flow, then the water level in this aquifer may rise to a level that is greater or less than the elevation of the actual water table. The elevation of the water in this deeper well is dependent upon the pressure in the deeper aquifer and is referred to as the potentiometric surface, not the water table.[2]

- ^ "What is the Water Table?". imnh.isu.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-25.

- ^ a b Freeze, R. Allan; Cherry, John A. (1979). Groundwater. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 9780133653120. OCLC 252025686.[page needed]

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search