Back Pastori delle steppe occidentali Italian 西部ステップ牧畜民 Japanese დასავლეთის სტეპის მესაქონლეები Georgian Vakarų stepių pastoralistai Lithuanian Западные степные скотоводы Russian Западни степски сточари Serbian

In archaeogenetics, the term Western Steppe Herders (WSH), or Western Steppe Pastoralists, is the name given to a distinct ancestral component first identified in individuals from the Chalcolithic steppe around the turn of the 5th millennium BC, subsequently detected in several genetically similar or directly related ancient populations including the Khvalynsk, Sredny Stog, and Yamnaya cultures, and found in substantial levels in contemporary European, West Asian and South Asian populations.[a][b] This ancestry is often referred to as Yamnaya ancestry, Yamnaya-related ancestry, Steppe ancestry or Steppe-related ancestry.[6]

Western Steppe Herders are considered to be descended from a merger between Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHGs) and Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers (CHGs). The WSH component is modeled as an admixture of EHG and CHG ancestral components in roughly equal proportions, with the majority of the Y-DNA haplogroup contribution from EHG males. The Y-DNA haplogroups of Western Steppe Herder males are not uniform, with the Yamnaya culture individuals mainly belonging to R1b-Z2103 with a minority of I2a2, the earlier Khvalynsk culture also with mainly R1b but also some R1a, Q1a, J, and I2a2, and the later, high WSH ancestry Corded Ware culture individuals mainly belonging to haplogroup R1b in the earliest samples, with R1a-M417 becoming predominant over time.[7][8][9]

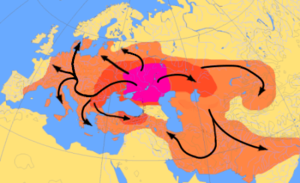

Around 3,000 BC, people of the Yamnaya culture or a closely related group,[2] who had high levels of WSH ancestry with some additional Neolithic farmer admixture,[5][10] embarked on a massive expansion throughout Eurasia, which is considered to be associated with the dispersal of at least some of the Indo-European languages by most contemporary linguists, archaeologists, and geneticists. WSH ancestry from this period is often referred to as Steppe Early and Middle Bronze Age (Steppe EMBA) ancestry.[c]

This migration is linked to the origin of both the Corded Ware culture, whose members were of about 75% WSH ancestry, and the Bell Beaker ("Eastern group"), who were around 50% WSH ancestry, though the exact relationships between these groups remains uncertain.[11]

The expansion of WSHs resulted in the virtual disappearance of the Y-DNA of Early European Farmers (EEFs) from the European gene pool, significantly altering the cultural and genetic landscape of Europe. During the Bronze Age, Corded Ware people with admixture from Central Europe remigrated onto the steppe, forming the Sintashta culture and a type of WSH ancestry often referred to as Steppe Middle and Late Bronze Age (Steppe MLBA) or Sintashta-related ancestry.[c]

Through the Andronovo culture and Srubnaya culture, Steppe MLBA was carried into Central Eurasia and South Asia along with Indo-Iranian languages, leaving a long-lasting cultural and genetic legacy.

The modern population of Europe can largely be modeled as a mixture of WHG (Western Hunter-Gatherer), EEF and WSH. According to a 2024 study, WSH ancestry peaks in Ireland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden.[12] In South Asia, it peaks among the Kalash, Ror, Jat, Brahmin and Bhumihar.[2][4][13][14] The modern day Yaghnobis, an Eastern Iranian peoples, and to a lesser extent modern-day Tajiks, display genetic continuity to Iron Age Central Asian Indo-Iranians, and may be used as proxy for the source of "Steppe ancestry" among many Central Asian and Middle Eastern groups.[15][16][17]

- ^ Hanel, Andrea; Carlberg, Carsten (July 3, 2020). "Skin colour and vitamin D: An update". Experimental Dermatology. 29 (9): 864–875. doi:10.1111/exd.14142. PMID 32621306.

- ^ a b c Haak et al. 2015.

- ^ a b Jeong et al. 2018.

- ^ a b Narasimhan et al. 2019.

- ^ a b Wang et al. 2019.

- ^ a b Jeong et al. 2019.

- ^ Anthony 2019a, pp. 1–19.

- ^ Malmström et al. 2019.

- ^ Papac et al. 2021.

- ^ Lazaridis et al. 2022.

- ^ Preda, Bianca (May 6, 2020). "Yamnaya - Corded Ware - Bell Beakers: How to conceptualise events of 5000 years ago". The Yamnaya Impact On Prehistoric Europe. University of Helsinki. Retrieved August 5, 2021. (Heyd 2019)

- ^ Irving-Pease, Evan K.; Refoyo-Martínez, Alba; Barrie, William; Ingason, Andrés; Pearson, Alice; Fischer, Anders; Sjögren, Karl-Göran; Halgren, Alma S.; Macleod, Ruairidh; Demeter, Fabrice; Henriksen, Rasmus A.; Vimala, Tharsika; McColl, Hugh; Vaughn, Andrew H.; Speidel, Leo (January 2024). "The selection landscape and genetic legacy of ancient Eurasians". Nature. 625 (7994): 312–320. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06705-1. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 10781624. PMID 38200293.

- ^ Lazaridis et al. 2016.

- ^ Pathak, Ajai K.; Kadian, Anurag; Kushniarevich, Alena; Montinaro, Francesco; Mondal, Mayukh; Ongaro, Linda; Singh, Manvendra; Kumar, Pramod; Rai, Niraj; Parik, Jüri; Metspalu, Ene; Rootsi, Siiri; Pagani, Luca; Kivisild, Toomas; Metspalu, Mait (December 6, 2018). "The Genetic Ancestry of Modern Indus Valley Populations from Northwest India". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 103 (6): 918–929. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.10.022. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 6288199. PMID 30526867.

- ^ Guarino-Vignon, Perle; Marchi, Nina; Bendezu-Sarmiento, Julio; Heyer, Evelyne; Bon, Céline (January 14, 2022). "Genetic continuity of Indo-Iranian speakers since the Iron Age in southern Central Asia". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 733. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12..733G. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-04144-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8760286. PMID 35031610.

- ^ Dai, Shan-Shan; Sulaiman, Xierzhatijiang; Isakova, Jainagul; Xu, Wei-Fang; Abdulloevich, Najmudinov Tojiddin; Afanasevna, Manilova Elena; Ibrohimovich, Khudoidodov Behruz; Chen, Xi; Yang, Wei-Kang; Wang, Ming-Shan; Shen, Quan-Kuan; Yang, Xing-Yan; Yao, Yong-Gang; Aldashev, Almaz A; Saidov, Abdusattor (August 25, 2022). "The Genetic Echo of the Tarim Mummies in Modern Central Asians". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 39 (9). doi:10.1093/molbev/msac179. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 9469894. PMID 36006373.

Given the Steppe-related ancestry (e.g., Andronovo) existing in Scythians (i.e., Saka; Unterländer et al. 2017; Damgaard et al. 2018; Guarino-Vignon et al. 2022), the proposed linguistic and physical anthropological links between the Tajiks and Scythians (Han 1993; Kuz′mina and Mallory 2007) may be ascribed to their shared Steppe-related ancestry.

- ^ Cilli, Elisabetta; Sarno, Stefania; Gnecchi Ruscone, Guido Alberto; Serventi, Patrizia; De Fanti, Sara; Delaini, Paolo; Ognibene, Paolo; Basello, Gian Pietro; Ravegnini, Gloria; Angelini, Sabrina; Ferri, Gianmarco; Gentilini, Davide; Di Blasio, Anna Maria; Pelotti, Susi; Pettener, Davide (April 2019). "The genetic legacy of the Yaghnobis: A witness of an ancient Eurasian ancestry in the historically reshuffled central Asian gene pool". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 168 (4): 717–728. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23789. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 30693949. S2CID 59338572.

Although the Yaghnobis do not show evident signs of recent admixture, they could be considered a modern proxy for the source of gene flow for many Central Asian and Middle Eastern groups. Accordingly, they seem to retain a peculiar genomic ancestry probably ascribable to an ancient gene pool originally wide spread across a vast area and subsequently reshuffled by distinct demographic events occurred in Middle East and Central Asia.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search