Back Virus Afrikaans Virus (Medizin) ALS ቫይረስ Amharic Virus AN Clēofanwyrm ANG فيروس Arabic ܒܝܪܘܣ ARC فيروس ARZ ভাইৰাছ Assamese Virus AST

| Virus | |

|---|---|

| |

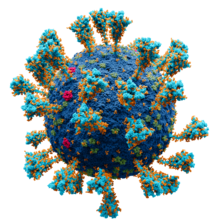

| SARS-CoV-2, a member of the subfamily Coronavirinae | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realms | |

A virus is a tiny parasite.[1] Virology is the study of viruses.

Viruses can only be seen under an electron microscope. Viruses are not free-living: they can only be parasites. They always reproduce inside other living things. All viruses infect living organisms, and may cause disease. The virus make copies of itself inside another organism's cells. Viruses are a strand of nucleic acid with a protein coat. Usually the nucleic acid is RNA; sometimes it is DNA. Viruses cause many types of diseases, such as polio, ebola and hepatitis.

Viruses reproduce by getting their nucleic acid strand into a prokaryote or eukaryote cell. The RNA or DNA strand then takes over the cell machinery to reproduce copies of itself and the protein coat. The cell then bursts open, spreading the newly created viruses. All viruses reproduce this way, and there are no free-living viruses.[2][3] Viruses are everywhere in the environment, and all organisms can be infected by them.[4][5][6]

Most viruses are much smaller than bacteria. They were not visible until the invention of the electron microscope. A virus has a simple structure. It has just a protein coat which covers a string of nucleic acid. Viruses live and reproduce inside the cells of other living organisms.

With eukaryotic cells, the virus protein coat is able to enter the target cells by certain cell membrane receptors. With prokaryote bacteria cells, the bacteriophage physically injects the nucleic acid strand into the host cell.

Viruses have the following characteristics:

- They outnumber all other forms of life on the planet by a long way.[1]

- They are infectious particles, causing many types of disease;

- They contain a nucleic acid core of RNA or DNA;

- They are surrounded by a protective protein coat;

When the host cell has finished making more viruses, it undergoes lysis, or breaks apart. The viruses are released and are then able to infect other cells. Viruses can remain "silent" (inactive) for a long time, and will infect cells when the time and conditions are right.

Some special viruses are worth noting. Bacteriophages have evolved to enter bacterial cells, which have a different type of cell wall from eukaryote cell membranes. Envelope viruses, when they reproduce, cover themselves with a modified form of the host cell membrane, thus gaining an outer lipid layer that helps entry. Some of our most difficult-to-combat viruses, like influenza and HIV, use this method.

Viral infections in animals trigger an immune response which usually kills the infecting virus. Vaccines can also produce immune responses. They give an artificially acquired immunity to the specific viral infection. However, some viruses (including those causing AIDS and viral hepatitis) escape from these immune responses and cause chronic infections. Antibiotics have no effect on viruses, but there are some other drugs which can be used against viruses.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Glaunsinger, Britt 2020 Viruses reveal the secrets of biology. [1] This source makes the astonishing claim that there are !024 viral infections/second.

- ↑ Dimmock N.J; Easton, Andrew J; Leppard, Keith 2007. Introduction to modern virology. 6th ed, Blackwell. ISBN 1-4051-3645-6

- ↑ Shors Teri 2017. Understanding viruses. Jones and Bartlett. ISBN 978-1-284-02592-7

- ↑ Breitbart M, Rohwer F (2005). "Here a virus, there a virus, everywhere the same virus?". Trends Microbiol. 13 (6): 278–84. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2005.04.003. PMID 15936660.

- ↑ Lawrence CM, Menon S, Eilers BJ; et al. (2009). "Structural and functional studies of archaeal viruses". J. Biol. Chem. 284 (19): 12599–603. doi:10.1074/jbc.R800078200. PMC 2675988. PMID 19158076.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Edwards RA, Rohwer F (2005). "Viral metagenomics". Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3 (6): 504–10. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1163. PMID 15886693. S2CID 8059643.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search