Back Alfabet Afrikaans Alphabet ALS አልፋቤት Amharic Alfabeto AN वर्णमाला ANP ألفبائية Arabic ܐܠܦܒܝܬ ARC Alfabetu AST Itasinahikewin ATJ वर्णमाला AWA

An alphabet is a standard set of letters written to represent particular sounds in a spoken language. Specifically, letters correspond to phonemes, the categories of sounds that can distinguish one word from another in a given language.[1] Not all writing systems represent language in this way: a syllabary assigns symbols to spoken syllables, while logographies assign symbols to words, morphemes, or other semantic units.[2][3]

The first letters were invented in Ancient Egypt to serve as an aid in writing Egyptian hieroglyphs; these are referred to as Egyptian uniliteral signs by lexicographers.[4] This system was used until the 5th century AD,[5] and fundamentally differed by adding pronunciation hints to existing hieroglyphs that had previously carried no pronunciation information. Later on, these phonemic symbols also became used to transcribe foreign words.[6] The first fully phonemic script was the Proto-Sinaitic script, also descending from Egyptian hieroglyphics, which was later modified to create the Phoenician alphabet. The Phoenician system is considered the first true alphabet and is the ultimate ancestor of many modern scripts, including Arabic, Cyrillic, Greek, Hebrew, Latin, and possibly Brahmic.[7][8][9][10]

Peter T. Daniels distinguishes true alphabets—which use letters to represent both consonants and vowels—from both abugidas and abjads, which only need letters for consonants. Abjads generally lack vowel indicators altogether, while abugidas represent them with diacritics added to letters. In this narrower sense, the Greek alphabet was the first true alphabet;[11][12] it was originally derived from the Phoenician alphabet, which was an abjad.[13]

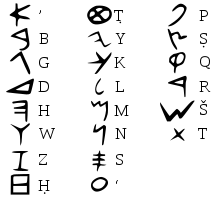

Alphabets usually have a standard ordering for their letters. This makes alphabets a useful tool in collation, as words can be listed in a well-defined order—commonly known as alphabetical order. This also means that letters may be used as a method of "numbering" ordered items. Letters also have names in some languages; this is known as acrophony, and it is present in scripts including Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, and Syriac. However, acrophony is not present in all languages, such as the Latin alphabet, which simply adds a vowel after the character representing each letter. Some systems also used to have acrophony but later abandoned it, such as Cyrillic.

- ^ Pulgram, Ernst (1951). "Phoneme and Grapheme: A Parallel". WORD. 7 (1): 15–20. doi:10.1080/00437956.1951.11659389. ISSN 0043-7956.

- ^ Daniels & Bright 1996, p. 4

- ^ Taylor, Insup (1980), Kolers, Paul A.; Wrolstad, Merald E.; Bouma, Herman (eds.), "The Korean writing system: An alphabet? A syllabary? A logography?", Processing of Visible Language, Boston, MA: Springer, pp. 67–82, ISBN 978-1-468-41070-9, retrieved 19 June 2021

- ^ Himelfarb, Elizabeth J. "First Alphabet Found in Egypt", Archaeology 53, Issue 1 (January/February 2000): 21.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Houston-2003was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Danielswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Coulmas 140was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Daniels & Bright 1996, pp. 92–96

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Goldwasser-2012was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Goldwasser, O. (2010). "How the Alphabet was Born from Hieroglyphs". Biblical Archaeology Review. 36 (2): 40–53.

- ^ Coulmas, Florian (1996). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-21481-6.

- ^ Millard 1986, p. 396

- ^ Daniels & Bright 1996, pp. 3–5, 91, 261–281.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search