Back Pico petrolero AN ذروة النفط Arabic Pic petrolier Catalan Ropný zlom Czech Ölfördermaximum German Κορύφωση παραγωγής πετρελαίου Greek Pinta nafto Esperanto Pico petrolero Spanish Naftatootmise tipp Estonian Petrolioaren gailurra Basque

Peak oil is the theorized point in time when the maximum rate of global oil production will occur, after which oil production will begin an irreversible decline.[2][3][4] The primary concern of peak oil is that global transportation heavily relies upon the use of gasoline and diesel fuel. Switching transportation to electric vehicles, biofuels, or more fuel-efficient forms of travel (trains, waterways) may help reduce oil demand.[5]

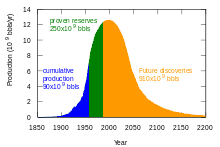

Peak oil is very closely related to the concept of oil depletion; while global petroleum reserves are finite, the limiting factor is not whether the oil exists but whether it can be extracted economically at a given price.[6][7] Historically, it was theorized that a secular decline in oil production would be caused by eventual depletion of known reserves, though more recently a new competing theory has emerged - that reductions in oil demand may reduce the price of oil relative to the cost of extraction, as might be induced to reduce carbon emissions. Or, demand may be reduced from demand destruction triggered by persistently high oil prices.[6][8]

Numerous predictions of the timing of peak oil have been made over the past century before being falsified by subsequent growth in the rate of petroleum extraction.[9][10][11][12][13] M. King Hubbert is often credited with introducing the notion in a 1956 paper which presented a formal theory and predicted U.S. extraction to peak between 1965 and 1971.[14][15] Hubbert's original predictions for world peak oil production proved premature[15] and, as of 2023[update], forecasts of the year of peak oil range from 2025 to 2040.[16] These predictions are dependent on future economic trends, technological developments, and efforts by societies and governments to mitigate climate change.[8][17][18]

- ^ "International - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "Peak oil theory". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ "Executive summary – Oil 2023 – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ "Transatlantic resilience brings peak oil within sight". www.ft.com. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ "Transport biofuels – Renewables 2023 – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

Biofuels and renewable electricity are set to reduce transport sector oil demand by near 4 mboe/d by 2028, more than 7% of forecast transport oil demand, and when electricity from non-renewable sources such as nuclear, natural gas and coal is taken into account, this value rises to nearly 9%.

- ^ a b "Petroleum - Status of the world oil supply". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ Clemente, Jude. "U.S. Oil Reserves, Resources, and Unlimited Future Supply". Forbes. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Wells, Wires, and Wheels - EROCI and the Tough Road Ahead for Oil". Investors' Corner. 2 August 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ David White, "The unmined supply of petroleum in the United States," Transactions of the Society of Automotive Engineers, 1919, v.14, part 1, p.227.

- ^ Hubbert, Marion King (June 1956). Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels 'Drilling and Production Practice' (PDF). Spring Meeting of the Southern District. Division of Production. American Petroleum Institute. San Antonio, Texas: Shell Development Company. pp. 22–27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2008.

- ^ Noel Grove; reporting M. King Hubbert (June 1974). "Oil, the Dwindling Treasure". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2007.

- ^ Kenneth S. Deffeyes, Hubbert's Peak: The Impending World Oil Shortage (Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 2001).

- ^ Daniel Yergin, "There will be oil," Wall Street Journal, 17 September 2011.

- ^ Hubbert, Marion King (June 1956). Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels 'Drilling and Production Practice' (PDF). Spring Meeting of the Southern District. Division of Production. American Petroleum Institute. San Antonio, Texas: Shell Development Company. pp. 22–27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2008.

- ^ a b Miller, R. G.; Sorrell, S. R. (2 December 2013). "The future of oil supply". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 372 (2006): 20130179. Bibcode:2013RSPTA.37230179M. doi:10.1098/rsta.2013.0179. PMC 3866387. PMID 24298085.

- ^ "The Tipping Point in Global Oil Demand".

- ^ "Global oil demand may have passed peak, says BP energy report". The Guardian. 13 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Now near 100 million bpd, when will oil demand peak?". Sustainability. 2 October 2018. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search