Back الحرب الأهلية السلفادورية Arabic Guerra civil d'El Salvador AST Грамадзянская вайна ў Сальвадоры Byelorussian Грамадзянская вайна ў Сальвадоры BE-X-OLD Guerra Civil del Salvador Catalan Salvadorská občanská válka Czech Εμφύλιος Πόλεμος του Ελ Σαλβαδόρ Greek Intercivitana Milito de Salvadoro Esperanto Guerra civil de El Salvador Spanish El Salvadorko Gerra Zibila Basque

| Salvadoran Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Central American crisis and the Cold War | |||||||

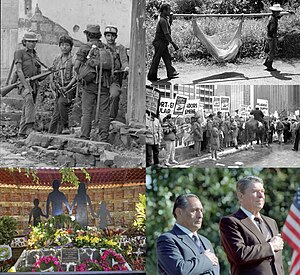

Clockwise from top right: two Salvadorans carrying a casualty of war, an anti-war protest in Chicago, Salvadoran President José Napoleón Duarte and U.S. President Ronald Reagan, a memorial to the El Mozote massacre, ERP fighters in Perquín | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 10,360+ killed[13] | 12,274[13] – 20,000 killed[14] | ||||||

|

65,161+ civilians killed[13] 5,292+ disappeared[13] 550,000 internally displaced 500,000 refugees in other countries[8][15][16] | |||||||

The Salvadoran Civil War (Spanish: guerra civil de El Salvador) was a twelve-year period of civil war in El Salvador that was fought between the government of El Salvador and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), a coalition or "umbrella organization" of left-wing groups backed by the Cuban regime of Fidel Castro as well as the Soviet Union.[17] A coup on 15 October 1979 followed by government killings of anti-coup protesters is widely seen as the start of civil war.[18] The war did not formally end until after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when, on 16 January 1992 the Chapultepec Peace Accords were signed in Mexico City.[19]

The United Nations (UN) reports that the war killed more than 75,000 people between 1979 and 1992, along with approximately 8,000 disappeared persons. Human rights violations, particularly the kidnapping, torture, and murder of suspected FMLN sympathizers by state security forces and paramilitary death squads – were pervasive.[20][21][22]

The Salvadoran government was considered an ally of the U.S. in the context of the Cold War.[23] During the Carter and Reagan administrations, the US provided 1 to 2 million dollars per day in economic aid to the Salvadoran government.[24] The US also provided significant training and equipment to the military. By May 1983, it was reported that US military officers were working within the Salvadoran High Command and making important strategic and tactical decisions.[25] The United States government believed its extensive assistance to El Salvador's government was justified on the grounds that the insurgents were backed by the Soviet Union.[26]

Counterinsurgency tactics implemented by the Salvadoran government often targeted civilian noncombatants. Overall, the United Nations estimated that FMLN guerrillas were responsible for 5 percent of atrocities committed during the civil war, while 85 percent were committed by the Salvadoran security forces.[27] Accountability for these civil war-era atrocities has been hindered by a 1993 amnesty law. In 2016, however, the Supreme Court of Justice of El Salvador ruled in case Incostitucionalidad 44-2013/145-2013[28] that the law was unconstitutional and that the Salvadoran government could prosecute suspected war criminals.[29]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

McClintock_1985was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

honourswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ El Salvador, In Depth, Negotiating a settlement to the conflict. Uppsala Conflict Data Program Conflict Encyclopedia. Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University.

US government increased the security support to prevent a similar thing to happen in El Salvador. This was, not least, demonstrated in the delivery of security aid to El Salvador

- ^ a b c Michael W. Doyle, Ian Johnstone & Robert Cameron Orr (1997). Keeping the Peace: Multidimensional UN Operations in Cambodia and El Salvador. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 222. ISBN 978-0521588379.

- ^ a b María Eugenia Gallardo & José Roberto López (1986). Centroamérica. San José: IICA-FLACSO, p. 249. ISBN 978-9290391104.

- ^ "Dirección de Asuntos del Hemisferio Occidental: Información general-- El Salvador". U.S. State Department. 18 November 2004. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014.

- ^ Armed with M16, IMI Galil and G3 assault rifles. Uzi submachine guns. Heavy weapons including artillery and missiles of North American manufacturing and helicopters and fighter jets

- ^ a b Andrews Bounds (2001). South America, Central America and The Caribbean 2002. El Salvador: History (10a ed.). London: Routledge. p. 384. ISBN 978-1857431216.

- ^ Charles Hobday (1986). Communist and Marxist parties of the world. New York: Longman, p. 323. ISBN 978-0582902640.

- ^ "El Salvador 30 años del FMLN". El Economista. 13 de octubre de 2010.

- ^ 2006 – Manuel Guedán – Carta del Director. Un Salvador violento celebra quince años de paz, article in Quorum. Journal of Latin American Thought, winter, number 016, University of Alcala, Madrid, Spain, pp. 6–11

- ^ Armed with: Assault rifle AK-47 and M16, Machine guns RPK and PKM and handmade explosives.

- ^ a b c d Seligson, Mitchell A.; McElhinny, Vincent. Low Intensity Warfare, High Intensity Death: The Demographic Impact of the Wars in El Salvador and Nicaragua (PDF). University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ Irvine, Reed and Joseph C. Goulden. "U.S. left's 'big lie' about El Salvador deaths." Human Events (9/15/90): 787.

- ^ Dictionary of Wars, by George Childs Kohn (Facts on File, 1999)

- ^ Britannica, 15th edition, 1992 printing

- ^ Oñate, Andrea (15 April 2011). "The Red Affair: FMLN–Cuban relations during the Salvadoran Civil War, 1981–92". Cold War History. 11 (2): 133–154. doi:10.1080/14682745.2010.545566. S2CID 153325313. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Wood, Elizabeth (2003). Insurgent Collective Action and Civil War in El Salvador. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Chapultepec Peace Agreement" (PDF). UCDP. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ Report of the UN Truth Commission on El Salvador (Report). United Nations. 1 April 1993.

- ^ "'Removing the Veil': El Salvador Apologizes for State Violence on 20th Anniversary of Peace Accords". NACLA. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ "El Salvador's Funes apologizes for civil war abuses". Reuters. 16 January 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ Danner, Mark (1993). The Massacre at El Mozote. Vintage Books. pp. 9. ISBN 067975525X.

- ^ El Salvador, In Depth: Negotiating a settlement to the conflict. Uppsala Conflict Data Program Conflict Encyclopedia. Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

While nothing of the aid delivered from the US in 1979 was earmarked for security purposes, the 1980 aid for security only summed US$6.2 million, close to two-thirds of the total aid in 1979.

- ^ "philly.com: The Philadelphia Inquirer Historical Archive (1860–1922)" – via nl.newsbank.com.[dead link]

- ^ Stokes, Doug (9 August 2006). "Countering the Soviet Threat? An Analysis of the Justifications for US Military Assistance to El Salvador, 1979–92". Cold War History. 3 (3): 79–102. doi:10.1080/14682740312331391628. S2CID 154097583. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ "Truth Commission: El Salvador". 1 July 1992. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "Incostitucionalidad 44-2013/145-2013" (PDF) (in Spanish). Supreme Court of Justice of El Salvador. 13 July 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ COHA (25 July 2016). "El Salvador's 1993 Amnesty Law Overturned: Implications for Colombia".

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search