Back تسمم بأحادي أكسيد الكربون Arabic কার্বন মনোক্সাইড বিষক্রিয়া Bengali/Bangla Intoxicació per monòxid de carboni Catalan Otrava oxidem uhelnatým Czech Kohlenstoffmonoxidintoxikation German Δηλητηρίαση από μονοξείδιο του άνθρακα Greek Intoxicación por monóxido de carbono Spanish Vingumürgistus Estonian مسمومیت با کربن منوکسید Persian Häkämyrkytys Finnish

| Carbon monoxide poisoning | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Carbon monoxide intoxication, carbon monoxide toxicity, carbon monoxide overdose |

| |

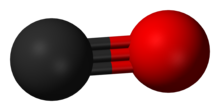

| Carbon monoxide | |

| Specialty | Toxicology, emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Headache, dizziness, weakness, vomiting, chest pain, confusion[1] |

| Complications | Loss of consciousness, arrhythmias, seizures[1][2] |

| Causes | Breathing in carbon monoxide[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Carbonylhemoglobin level: 3% (nonsmokers) 10% (smokers)[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Cyanide toxicity, alcoholic ketoacidosis, aspirin poisoning, upper respiratory tract infection[2][4] |

| Prevention | Carbon monoxide detectors, venting of gas appliances, maintenance of exhaust systems[1] |

| Treatment | Supportive care, 100% oxygen, hyperbaric oxygen therapy[2] |

| Prognosis | Risk of death: 1–31%[2] |

| Frequency | >20,000 emergency visits for non-fire related cases per year (US)[1] |

| Deaths | >400 non-fire related a year (US)[1] |

Carbon monoxide poisoning typically occurs from breathing in carbon monoxide (CO) at excessive levels.[3] Symptoms are often described as "flu-like" and commonly include headache, dizziness, weakness, vomiting, chest pain, and confusion.[1] Large exposures can result in loss of consciousness, arrhythmias, seizures, or death.[1][2] The classically described "cherry red skin" rarely occurs.[2] Long-term complications may include chronic fatigue, trouble with memory, and movement problems.[5]

CO is a colorless and odorless gas which is initially non-irritating.[5] It is produced during incomplete burning of organic matter.[5] This can occur from motor vehicles, heaters, or cooking equipment that run on carbon-based fuels.[1] Carbon monoxide primarily causes adverse effects by combining with hemoglobin to form carboxyhemoglobin (symbol COHb or HbCO) preventing the blood from carrying oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide as carbaminohemoglobin.[5] Additionally, many other hemoproteins such as myoglobin, Cytochrome P450, and mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase are affected, along with other metallic and non-metallic cellular targets.[2][6]

Diagnosis is typically based on a HbCO level of more than 3% among nonsmokers and more than 10% among smokers.[2] The biological threshold for carboxyhemoglobin tolerance is typically accepted to be 15% COHb, meaning toxicity is consistently observed at levels in excess of this concentration.[7] The FDA has previously set a threshold of 14% COHb in certain clinical trials evaluating the therapeutic potential of carbon monoxide.[8] In general, 30% COHb is considered severe carbon monoxide poisoning.[9] The highest reported non-fatal carboxyhemoglobin level was 73% COHb.[9]

Efforts to prevent poisoning include carbon monoxide detectors, proper venting of gas appliances, keeping chimneys clean, and keeping exhaust systems of vehicles in good repair.[1] Treatment of poisoning generally consists of giving 100% oxygen along with supportive care.[2][5] This procedure is often carried out until symptoms are absent and the HbCO level is less than 3%/10%.[2]

Carbon monoxide poisoning is relatively common, resulting in more than 20,000 emergency room visits a year in the United States.[1][10] It is the most common type of fatal poisoning in many countries.[11] In the United States, non-fire related cases result in more than 400 deaths a year.[1] Poisonings occur more often in the winter, particularly from the use of portable generators during power outages.[2][12] The toxic effects of CO have been known since ancient history.[13][9] The discovery that hemoglobin is affected by CO emerged with an investigation by James Watt and Thomas Beddoes into the therapeutic potential of hydrocarbonate in 1793, and later confirmed by Claude Bernard between 1846 and 1857.[9]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k National Center for Environmental Health (30 December 2015). "Carbon Monoxide Poisoning – Frequently Asked Questions". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Guzman JA (October 2012). "Carbon monoxide poisoning". Critical Care Clinics. 28 (4): 537–48. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2012.07.007. PMID 22998990.

- ^ a b Schottke D (2016). Emergency Medical Responder: Your First Response in Emergency Care. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 224. ISBN 978-1284107272. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Caterino JM, Kahan S (2003). In a Page: Emergency medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 309. ISBN 978-1405103572. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Bleecker ML (2015). "Carbon monoxide intoxication". Occupational Neurology. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 131. pp. 191–203. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-62627-1.00024-X. ISBN 978-0444626271. PMID 26563790.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:2was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Motterlini R, Foresti R (March 2017). "Biological signaling by carbon monoxide and carbon monoxide-releasing molecules". American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 312 (3): C302–C313. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00360.2016. PMID 28077358.

- ^ Yang X, de Caestecker M, Otterbein LE, Wang B (July 2020). "Carbon monoxide: An emerging therapy for acute kidney injury". Medicinal Research Reviews. 40 (4): 1147–1177. doi:10.1002/med.21650. PMC 7280078. PMID 31820474.

- ^ a b c d Hopper CP, Zambrana PN, Goebel U, Wollborn J (June 2021). "A brief history of carbon monoxide and its therapeutic origins". Nitric Oxide. 111–112: 45–63. doi:10.1016/j.niox.2021.04.001. PMID 33838343. S2CID 233205099. Retrieved 6 November 2022 – via ScienceDirect.

- ^ Penney DG (2007). Carbon Monoxide Poisoning. CRC Press. p. 569. ISBN 978-0849384189. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Omaye ST (November 2002). "Metabolic modulation of carbon monoxide toxicity". Toxicology. 180 (2): 139–50. doi:10.1016/S0300-483X(02)00387-6. PMID 12324190.

- ^ Ferri FF (2016). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2017 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 227–28. ISBN 978-0323448383. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Blumenthal I (June 2001). "Carbon monoxide poisoning". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 94 (6): 270–2. doi:10.1177/014107680109400604. PMC 1281520. PMID 11387414.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search