Back غيل سكوت هارون Arabic جيل سكوت هارون ARZ قیل سکوت هارون AZB Gil Scott-Heron Breton Gil Scott-Heron Czech Gil Scott-Heron German Τζιλ Σκοτ-Χίρον Greek Gil Scott-Heron Esperanto Gil Scott-Heron Spanish Gil Scott-Heron Finnish

Gil Scott-Heron | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Gilbert Scott-Heron |

| Born | April 1, 1949 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Origin | New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | May 27, 2011 (aged 62) New York City, New York, U.S.[1] |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instrument(s) |

|

| Years active | 1969–2011 |

| Labels | |

| Parent(s) | Bobbie Scott and Gil Heron |

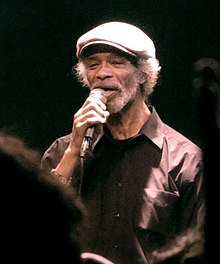

Gilbert Scott-Heron (April 1, 1949 – May 27, 2011)[8] was an American jazz poet, singer,[3] musician, and author known for his work as a spoken-word performer in the 1970s and 1980s. His collaborative efforts with musician Brian Jackson fused jazz, blues, and soul with lyrics relative to social and political issues of the time, delivered in both rapping and melismatic vocal styles. He referred to himself as a "bluesologist",[9] his own term for "a scientist who is concerned with the origin of the blues".[note 1][10] His poem "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised", delivered over a jazz-soul beat, is considered a major influence on hip hop music.[11]

Scott-Heron's music, most notably on the albums Pieces of a Man and Winter in America during the early 1970s, influenced and foreshadowed later African-American music genres, including hip hop and neo soul. His recording work received much critical acclaim, especially for "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised".[12] AllMusic's John Bush called him "one of the most important progenitors of rap music", stating that "his aggressive, no-nonsense street poetry inspired a legion of intelligent rappers while his engaging songwriting skills placed him square in the R&B charts later in his career."[6]

Scott-Heron remained active until his death, and in 2010 released his first new album in 16 years, entitled I'm New Here. A memoir he had been working on for years up to the time of his death, The Last Holiday, was published posthumously in January 2012.[13][14] Scott-Heron received a posthumous Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012. He also is included in the exhibits at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) that officially opened on September 24, 2016, on the National Mall, and in an NMAAHC publication, Dream a World Anew.[15] In 2021, Scott-Heron was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, as a recipient of the Early Influence Award.[16]

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron, Spoken-Word Musician, Dies at 62". The New York Times. Associated Press. May 28, 2011. Archived from the original on June 19, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

KotGwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Preston, Rohan B. (September 20, 1994). "Scott-Heron's Jazz Poetry Rich In Soul". The Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- ^ Paul, Anna (March 2016). "An Introduction To Gil Scott-Heron In 10 Songs". The Culture Trip. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ Woodstra, Chris; John Bush; Stephen Thomas Erlewine (2008). Old School Rap and Hip-hop. Backbeat Books. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-0-87930-916-9. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ a b Bush, John. "Gil Scott-Heron - Biography & History". AllMusic. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ Backus, Rob (1976). Fire Music: A Political History of Jazz (2nd ed.). Vanguard Books. ISBN 091770200X.

- ^ Tyler-Ameen, Daoud (May 27, 2011). "Gil Scott-Heron, Poet And Musician, Has Died". NPR. Archived from the original on May 9, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (May 28, 2011). "Gil Scott-Heron, Voice of Black Protest Culture, Dies at 62". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 30, 2011. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ Gil Scott-Heron in a live performance in 1982 with the Amnesia Express at the Black Wax Club, Washington, D.C. Black Wax (DVD). Directed by Robert Mugge.

- ^ Sharrock, David (May 28, 2011). "Gil Scott-Heron: music world pays tribute to the 'Godfather of Rap'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 21, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Azpiriwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Garner, Dwight (January 9, 2012). "'The Last Holiday: A Memoir' by Gil Scott-Heron – Review". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ Scott-Heron, Gil (January 8, 2012). "How Gil Scott-Heron and Stevie Wonder set up Martin Luther King Day". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on July 11, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ gilscottherononline.com

- ^ Limbong, Andrew (May 12, 2021). "Tina Turner, Jay-Z, Foo Fighters Among Those Inducted Into Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame". NPR. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search