Back مجنون ليلى (رواية) Arabic Leyli və Məcnun Azerbaijani Лейля и Маджнун Bulgarian লায়লী-মজনু Bengali/Bangla لەیلا و مەجنوون CKB Madschnūn Lailā German Λεϊλά και Μετζνούν Greek Lejla kaj Maĝnun Esperanto Layla y Majnún Spanish لیلی و مجنون Persian

|

| Part of a series on |

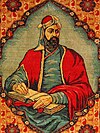

| Nizami Ganjavi |

|---|

| The Khamsa or Panj Ganj |

| Related topics |

| Monuments |

|

Nizami Mausoleum • Nizami Museum of Azerbaijani Literature • Nizami Gəncəvi (Baku Metro) • in Ganja • in Baku • in Beijing • in Chișinău • in Rome • in Saint Petersburg • in Tashkent |

Layla and Majnun (Arabic: مجنون ليلى majnūn laylā "Layla's Mad Lover"; Persian: لیلی و مجنون, romanized: laylâ-o-majnun)[1] is an old story of [Persian] origin,[2][3] about the 7th-century Persian poet Majnun and his lover Layla (later known as Layla al-Aamiriya).[4]

"The Layla-Majnun theme passed from Persian to Arabic, Turkish, and Indian languages",[5] through the narrative poem composed in 584/1188 by the Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi, as the third part of his Khamsa.[4][6][7][8][a] It is a popular poem praising their love story.[9][10][11]

Qays and Layla fell in love with each other when they were young, but when they grew up, Layla's father did not allow them to be together. Qays became obsessed with her. His tribe Banu 'Amir, and the community gave him the epithet of Majnūn (مجنون "crazy", lit. "possessed by Jinn"). Long before Nizami, the legend circulated in anecdotal forms in Iranian akhbar. The early anecdotes and oral reports about Majnun are documented in Kitab al-Aghani and Ibn Qutaybah's Al-Shi'r wa-l-Shu'ara'. The anecdotes are mostly very short, only loosely connected, and show little or no plot development. Nizami collected both secular and mystical sources about Majnun and portrayed a vivid picture of the famous lovers.[12] Subsequently, many other Persian poets imitated him and wrote their own versions of the romance.[12] Nizami drew influence from Udhrite (Udhri)[13][14] love poetry, which is characterized by erotic abandon and attraction to the beloved, often by means of an unfulfillable longing.[15]

Many imitations have been contrived of Nizami's work, several of which are original literary works in their own right, including Amir Khusrow Dehlavi's Majnun o Leyli (completed in 1299), and Jami's version, completed in 1484, amounting to 3,860 couplets. Other notable reworkings are by Maktabi Shirazi, Hatefi (died 1520), and Fuzuli (died 1556), which became popular in Ottoman Turkey and India. Sir William Jones published Hatefi's romance in Calcutta in 1788. The popularity of the romance following Nizami's version is also evident from the references to it in lyrical poetry and mystical masnavis—before the appearance of Nizami's romance, there are just some allusions to Layla and Majnun in divans. The number and variety of anecdotes about the lovers also increased considerably from the twelfth century onwards. Mystics contrived many stories about Majnun to illustrate technical mystical concepts such as fanaa (annihilation), divānagi (love-madness), self-sacrifice, etc. Nizami's work has been translated into many languages.[16] The modern Arabic-language adaptation of the classical Arabic story include Shawqi's play The Mad Lover of Layla.[17]

- ^ Banipal: Magazine of Modern Iran Literature. 2003.

- ^ Schimmel, Annemarie (2014). A Two-Colored Brocade: The Imagery of Persian Poetry. p. 131.

Indeed, the old Iranian love story of Majnun and Layla became a favorite topic among Persian poets.

- ^ The Islamic Review & Arab Affairs. Vol. 58. 1970. p. 32.

Nizāmī's next poem was an even more popular lovestory, Layla and Majnun, of Persian origin.

- ^ a b electricpulp.com. "LEYLI O MAJNUN – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ The Posthumous career of Manuel Puig. 1991. p. 758.

- ^ Bruijn, J. T. P. de; Yarshater, Ehsan (2009). General Introduction to Persian Literature: A History of Persian Literature. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845118860.

- ^ PhD, Evans Lansing Smith; Brown, Nathan Robert (2008). The Complete Idiot's Guide to World Mythology. Penguin. ISBN 9781101047163.

- ^ Grose, Anouschka (2011). No More Silly Love Songs: A Realist's Guide To Romance. Granta Publications. ISBN 9781846273544.

- ^ "أدب .. الموسوعة العالمية للشعر العربي قيس بن الملوح (مجنون ليلى)". Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ^ al-hakawati.net/arabic/Civilizations/diwanindex2a4.pdf

- ^ "Visions of Azerbaijan Magazine ::: Nizami - Poet for all humanity".

- ^ a b Layli and Majnun: Love, Madness and Mystic Longing, Dr. Ali Asghar Seyed-Gohrab, Brill Studies in Middle Eastern literature, Jun 2003, ISBN 90-04-12942-1. excerpt: Although Majnun was to some extent a popular figure before Nizami’s time, his popularity increased dramatically after the appearance of Nizami’s romance. By collecting information from both secular and mystical sources about Majnun, Nizami portrayed such a vivid picture of this legendary lover that all subsequent poets were inspired by him, many of them imitated him and wrote their own versions of the romance. As is seen in the following chapters, the poet uses various characteristics deriving from ‘Udhrite love poetry and weaves them into his own Persian culture. In other words, Nizami Persianises the poem by adding several techniques borrowed from the Persian epic tradition, such as the portrayal of characters, the relationship between characters, description of time and setting, etc.

- ^ "Arabic literature - Love Poetry, Verse, Romance | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "Why love always hurts in udhri poetry". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Scroggins, Mark (1996). "Review". African American Review. doi:10.2307/3042384. JSTOR 3042384.

- ^ Seyed-Gohrab, A. A. (15 July 2009). "LEYLI O MAJNUN". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ Badawi, M.M. (1987). Modern Arabic Drama in Egypt. Cambridge University Press. p. 225. ISBN 9780521242226.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search