Back عمارة مغاربية Arabic Мавритан архитектураһы Bashkir Маўрытанскі стыль Byelorussian Мавританска архитектура Bulgarian Мавританин архитектура CE Maurský sloh Czech Maurischer Stil German Arquitectura morisca Spanish Mauri arhitektuur Estonian Architecture mauresque French

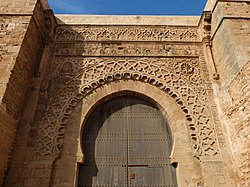

Top: Great Mosque of Córdoba, Spain (8th century); Centre: Bab Oudaya in Rabat, Morocco (late 12th century); Bottom: Court of the Lions at the Alhambra in Granada, Spain (14th century) | |

| Years active | 8th century to present day |

|---|---|

Moorish architecture is a style within Islamic architecture which developed in the western Islamic world, including al-Andalus (on the Iberian peninsula) and what is now Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia (part of the Maghreb).[1][2] Scholarly references on Islamic architecture often refer to this architectural tradition in terms such as architecture of the Islamic West[2][1][3] or architecture of the Western Islamic lands.[4][5][3] The use of the term "Moorish" comes from the historical Western European designation of the Muslim inhabitants of these regions as "Moors".[6][7][a] Some references on Islamic art and architecture consider this term to be outdated or contested.[11][12]

This architectural tradition integrated influences from pre-Islamic Roman, Byzantine, and Visigothic architectures,[6][13][2] from ongoing artistic currents in the Islamic Middle East,[4][13][6] and from North African Berber traditions.[1][14][6] Major centers of artistic development included the main capitals of the empires and Muslim states in the region's history, such as Córdoba, Kairouan, Fes, Marrakesh, Seville, Granada and Tlemcen. While Kairouan and Córdoba were some of the most important centers during the 8th to 10th centuries,[1][15] a wider regional style was later synthesized and shared across the Maghreb and al-Andalus thanks to the empires of the Almoravids and the Almohads, which unified both regions for much of the 11th to 13th centuries.[1][15][14][16] Within this wider region, a certain difference remained between architectural styles in the more easterly region of Ifriqiya (roughly present-day Tunisia) and a more specific style in the western Maghreb (present-day Morocco and western Algeria) and al-Andalus, sometimes referred to as Hispano-Moresque or Hispano-Maghrebi.[1]: viii–ix [4]: 121, 155

This architectural style came to encompass distinctive features such as the horseshoe arch, riad gardens (courtyard gardens with a symmetrical four-part division), square (cuboid) minarets, and elaborate geometric and arabesque motifs in wood, stucco, and tilework (notably zellij).[1][6][17][4] Over time, it made increasing use of surface decoration while also retaining a tradition of focusing attention on the interior of buildings rather than their exterior. Unlike Islamic architecture further east, western Islamic architecture did not make prominent use of large vaults and domes.[2]: 11

Even as Muslim rule ended on the Iberian Peninsula, the traditions of Moorish architecture continued in North Africa as well as in the Mudéjar style in Spain, which adapted Moorish techniques and designs for Christian patrons.[2][18] In Algeria and Tunisia local styles were subjected to Ottoman influence and other changes from the 16th century onward, while in Morocco the earlier Hispano-Maghrebi style was largely perpetuated up to modern times with fewer external influences.[2]: 243–245 In the 19th century and after, the Moorish style was frequently imitated in the form of Neo-Moorish or Moorish Revival architecture in Europe and America,[19] including Neo-Mudéjar in Spain.[20] Some scholarly references associate the term "Moorish" or "Moorish style" more narrowly with this 19th-century trend in Western architecture.[21][11]

- ^ a b c d e f g Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident (in French). Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

- ^ a b c d e f Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700–1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300218701.

- ^ a b Flood, Finbarr Barry; Necipoğlu, Gülru, eds. (2017). A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture. Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 9781119068662.

- ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

Bloom-2009awas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Ettinghausen, Richard; Grabar, Oleg; Jenkins-Madina, Marilyn (2001). Islamic Art and Architecture: 650–1250 (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300088670.

- ^ a b c d e Barrucand, Marianne; Bednorz, Achim (1992). Moorish architecture in Andalusia. Taschen. ISBN 3822876348.

- ^ Lévi-Provençal, E.; Donzel, E. van (1993). "Moors". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Vol. 7. Brill. pp. 235–236.

- ^ Gabriel Camps (2007). Les Berbères, Mémoire et Identité. pp. 116–118.

- ^ Menocal (2002). Ornament of the World Archived 8 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine, p. 16; Richard A Fletcher, Moorish Spain Archived 8 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine (University of California Press, 2006), pp.1,19.

- ^ Assouline, David (2009). "Moors". In Esposito, John L. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195305135.

- ^ a b Mudejarismo and Moorish Revival in Europe: Cultural Negotiations and Artistic Translations in the Middle Ages and 19th-century Historicism. Brill. 2021. p. 1. ISBN 978-90-04-44858-2.

The authors of this volume are conscious of the contested terminology of Mudéjar and the negative connotations of the term Moorish. They are used here as denominators of two phenomena that have been essentially shaped in the 19th century. When speaking of the Islamic architecture of al- Andalus, the term Moorish is rejected. In these cases, the terms Ibero-Islamic or andalusí are used.

- ^ Vernoit, Stephen (2017). "Islamic Art in the West: Categories of Collecting". In Flood, Finbarr Barry; Necipoğlu, Gülru (eds.). A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture. Wiley Blackwell. p. 1173. ISBN 978-1-119-06857-0.

Some terms such as "Saracenic," "Mohammedan," and "Moorish" are no longer fashionable.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Arnold-2017was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Salmon-2018was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Bennison, Amira K. (2016). "'The most wondrous artifice': The Art and Architecture of the Berber Empires". The Almoravid and Almohad Empires. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 276–328. ISBN 9780748646821.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Perez-1992was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Parker, Richard (1981). A practical guide to Islamic Monuments in Morocco. Charlottesville, VA: The Baraka Press.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Borrás Gualís-2018was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Moorish [Hindoo, Indo-Saracenic]". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 543–545. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Giese, Francine; Varela Braga, Ariane; Lahoz Kopiske, Helena; Kaufmann, Katrin; Castro Royo, Laura; Keller, Sarah (2016). "Resplendence of al-Andalus: Exchange and Transfer Processes in Mudéjar and Neo-Moorish Architecture" (PDF). Asiatische Studien – Études Asiatiques. 70 (4): 1307–1353. doi:10.1515/asia-2016-0499. S2CID 99943973.

- ^ M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Moorish [Hindoo, Indo-Saracenic]". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 543–545. ISBN 9780195309911.

Term used specifically in the 19th century to describe a Western style based on the architecture and decorative arts of the Muslim inhabitants (the Moors) of northwest Africa and (between 8th and 15th centuries) of southern Spain; it is often used imprecisely to include Arab and Indian influences

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search