Back Taijitu Afrikaans تاجيتو Arabic Taijitu AST তাই চি রেখাচিত্র Bengali/Bangla Taijitu Catalan Yin und Yang (Symbol) German Jino kaj Jango#Tajĝifiguro Esperanto Taijitu Spanish Taijitu French Taijitu ID

| Taijitu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Diagram of the Utmost Extremes[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 太極圖 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 太极图 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Thái cực đồ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 太極圖 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 태극 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 太極 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | たいきょくず | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Katakana | タイキョクズ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shinjitai | 太極図 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

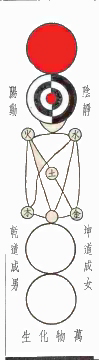

In Chinese philosophy, a taijitu (Chinese: 太極圖; pinyin: tàijítú; Wade–Giles: tʻai⁴chi²tʻu²) is a symbol or diagram (圖; tú) representing taiji (太極; tàijí; 'utmost extreme') in both its monist (wuji) and its dualist (yin and yang) forms in application as a deductive and inductive theoretical model. Such a diagram was first introduced by Neo-Confucian philosopher Zhou Dunyi of the Song Dynasty in his Taijitu shuo (太極圖說).

The Daozang, a Taoist canon compiled during the Ming dynasty, has at least half a dozen variants of the taijitu. The two most similar are the Taiji Xiantiandao and wujitu (無極圖; wújítú) diagrams, both of which have been extensively studied since the Qing period for their possible connection with Zhou Dunyi's taijitu.[2]

Ming period author Lai Zhide simplified the taijitu to a design of two interlocking spirals with two black-and-white dots superimposed on them, became synonymous with the Yellow River Map.[3][further explanation needed] This version was represented in Western literature and popular culture in the late 19th century as the "Great Monad",[4] this depiction became known in English as the "yin-yang symbol" since the 1960s.[5] The contemporary Chinese term for the modern symbol is referred to as "the two-part Taiji diagram" (太極兩儀圖).

Ornamental patterns with visual similarity to the "yin yang symbol" are found in archaeological artefacts of European prehistory; such designs are sometimes descriptively dubbed "yin yang symbols" in archaeological literature by modern scholars.[6][7][8]

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich (2021-05-06). "Taiji tushuo 太極圖說". Chinaknowledge. Retrieved 2023-05-03.

- ^ Adler 2014, p. 153

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich (2012-02-08). "Hetu luoshu 河圖洛書". Chinaknowledge. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

- ^ Labelled "The Great Monad" by Hampden Coit DuBose, The Dragon, Image, and Demon: Or, The Three Religions of China; Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism (1887), p. 357

- ^ "The 'River Diagram' is the pattern of black-and-white dots which appears superimposed on the interlocking spirals [...] Those spirals alone form the Taiji tu or 'Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate', often known in English since the 1960s as the 'yin-yang symbol'.) These dots were believed to be collated with the eight trigrams, and hence with the concepts of roundness and of the heavens, while the equally numinous 'Luo River Writing' was a pattern of dots accosiated with the number nine, with squareness and with the earth." Craig Clunas, Pictures and Visuality in Early Modern China (1997), p. 107.

- ^ Peyre 1982, pp. 62–64, 82 (pl. VI); Harding 2007, pp. 68f., 70f., 76, 79, 84, 121, 155, 232, 239, 241f., 248, 253, 259; Duval 1978, p. 282; Kilbride-Jones 1980, pp. 127 (fig. 34.1), 128; Laing 1979, p. 79; Verger 1996, p. 664; Laing 1997, p. 8; Mountain 1997, p. 1282; Leeds 2002, p. 38; Megaw 2005, p. 13

- ^ Peyre 1982, pp. 62–64

- ^ Monastra 2000; Nickel 1991, p. 146, fn. 5; White & Van Deusen 1995, pp. 12, 32; Robinet 2008, p. 934

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search