Back مقياس الإيقاع Arabic Памер (музыка) Byelorussian Taktové předznamenání Czech Arwydd amser Welsh Taktangabe German Taktindiko Esperanto Compás (música) Spanish Taktimõõt Estonian Konpas (musika) Basque کسر میزان Persian

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2019) |

4 time signature. The time signature indicates that there are three quarter notes (crotchets) per measure (bar).

A time signature (also known as meter signature,[1] metre signature,[2] and measure signature)[3] is a convention in Western music notation that specifies how many note values of a particular type are contained in each measure (bar). The time signature indicates the meter of a musical movement.

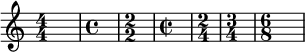

In a music score the time signature appears as two stacked numerals, such as 4

4 (spoken as four–four time), or a time symbol, such as ![]() (spoken as common time). It immediately follows the key signature (or if there is no key signature, the clef symbol). A mid-score time signature, usually immediately following a barline, indicates a change of meter.

(spoken as common time). It immediately follows the key signature (or if there is no key signature, the clef symbol). A mid-score time signature, usually immediately following a barline, indicates a change of meter.

Most time signatures are either simple (the note values are grouped in pairs, like 2

4, 3

4, and 4

4), or compound (grouped in threes, like 6

8, 9

8, and 12

8). Less-common signatures indicate complex, mixed, additive, and irrational meters.

4, also known as common time (

2, alla breve, also known as cut time or cut-common time (

4; 3

4; and 6

8

- ^ Alexander R. Brinkman, Pascal Programming for Music Research (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990): 443, 450–63, 757, 759, 767. ISBN 0226075079; Mary Elizabeth Clark and David Carr Glover, Piano Theory: Primer Level (Miami: Belwin Mills, 1967): 12; Steven M. Demorest, Building Choral Excellence: Teaching Sight-Singing in the Choral Rehearsal (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2003): 66. ISBN 0195165500; William Duckworth, A Creative Approach to Music Fundamentals, eleventh edition (Boston, MA: Schirmer Cengage Learning, 2013): 54, 59, 379. ISBN 0840029993; Edwin Gordon, Tonal and Rhythm Patterns: An Objective Analysis: A Taxonomy of Tonal Patterns and Rhythm Patterns and Seminal Experimental Evidence of Their Difficulty and Growth Rate (Albany: SUNY Press, 1976): 36–37, 54–55, 57. ISBN 0873953541; Demar Irvine, Reinhard G. Pauly, Mark A. Radice, Irvine’s Writing about Music, third edition (Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 1999): 209–210. ISBN 1574670492.

- ^ Henry Cowell and David Nicholls, New Musical Resources, third edition (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996): 63. ISBN 0521496519 (cloth); ISBN 0521499747 (pbk); Cynthia M. Gessele, "Thiéme, Frédéric [Thieme, Friedrich]", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001); James L. Zychowicz, Mahler's Fourth Symphony (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2005): 82–83, 107. ISBN 0195181654.

- ^ Edwin Gordon, Rhythm: Contrasting the Implications of Audiation and Notation (Chicago: GIA Publications, 2000): 111. ISBN 1579990983.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search