Back Operasie Condor Afrikaans عملية كوندور Arabic Kondor əməliyyatı Azerbaijani Операция Кондор Bulgarian Operació Còndor Catalan Operace Kondor Czech Ymgyrch Condor Welsh Operation Condor Danish Operation Condor German Επιχείρηση Κόνδορας Greek

| Operation Condor | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |

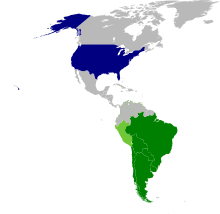

Main active members (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay) Sporadic member (Peru) Collaborator and financier (United States) | |

| Type | Covert operation |

| Location | |

| Planned by | Members:

Supported: |

| Commanded by | |

| Target | Democratic governments and political parties, unions, student organizations, journalists, artists, teachers, intellectuals, opponents to the military juntas and left-wing sympathizers (including socialists, peronists, anarchists and communists) |

| Date | 1975–1983 |

| Executed by | Intelligence agencies of respective participating countries |

| Outcome | Concluded after the fall of the Argentinean military junta |

| Casualties | 60,000–80,000 suspected leftist sympathizers killed[8] 400–500 killed in cross-border operations[8] 400,000+ political prisoners[9] |

Operation Condor (Portuguese: Operação Condor; Spanish: Operación Cóndor) was a campaign of political repression involving intelligence operations, coups, and assassinations of left-wing sympathizers, liberals and democrats and their families in South America which formally existed from 1975 to 1983.[10][11][12][13][14] Condor was formally created in November 1975, when Pinochet’s spy chief, Manuel Contreras, invited 50 intelligence officers from Chile, Uruguay, Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia and Brazil to the Army War Academy on La Alameda, Santiago’s central avenue, which comprised the right-wing dictatorships of the Southern Cone of South America.[11][12][15] The Archive of Terror documents revealed that there were at least 763 people kidnapped, tortured, raped, and murdered during Operation Condor.[12]

The United States[16][17][18] and, allegedly, France (which denies involvement)[19][20] were frequent collaborators and financiers of the covert operations. Due to its clandestine nature, the precise number of deaths directly attributable to Operation Condor is highly disputed. Some estimates are that at least 60,000 deaths can be attributed to Condor,[8] with up to 30,000 of these in Argentina. This collaboration had a devastating impact on countries like Argentina, where Condor exacerbated existing political violence and contributed to the "Dirty War" that left an estimated 30,000 people dead or disappeared.[21][22][23] The Archives of Terror list 50,000 killed, 30,000 disappeared and 400,000 imprisoned.[9][17] Additionally, American political scientist J. Patrice McSherry gives a figure of at least 402 killed in Condor operations which crossed national borders in a 2002 source,[16] and mentions in a 2009 source that of those who "had gone into exile" and were "kidnapped, tortured and killed in allied countries or illegally transferred to their home countries to be executed ... hundreds, or thousands, of such persons – the number still has not been finally determined – were abducted, tortured, and murdered in Condor operations."[24]

Victims included dissidents and leftists, union and peasant leaders, priests, monks and nuns, students and teachers, intellectuals, and suspected guerrillas such as prominent union leader Marcelo Santuray in Argentina or journalist Carlos Prats in Chile. One particularly awful tactic involved 'death flights,' where Condor operatives drugged political dissidents, threw them from airplanes into the ocean, and disappeared their bodies.[25][16] Although it was described by the CIA as "a cooperative effort by the intelligence/security services of several South American countries to combat terrorism and subversion",[26] combatting guerrillas was used as a pretext for its existence, as guerrillas were not substantial enough in numbers to control territory, gain material support by any foreign power, or otherwise threaten national security.[27][28][29] Condor's initial members were the governments of Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia; Brazil signed the agreement later on. Peru later joined the operation in a more peripheral role.[30][31] The United States government provided planning, coordinating, training on torture,[32] the Reagan administration.[33] Such support was at times routed through the CIA.[33] However, a letter which was written by renowned DINA assassin Michael Townley in 1976 noted the existence of a network of individual Southern Cone secret polices known as Red Condor.[34] With tensions between Chile and Argentina rising and Argentina severely weakened as a result of the loss in Falklands War to the British military, the Argentinean junta fell in 1983, which in turn led to more South American dictatorships falling.[12] The fall of the Argentinean junta has been regarded as marking in the end of Operation Condor.[10]

The political scientist J. Patrice McSherry has argued that aspects of Operation Condor fit the definition of state terrorism.[35]

- ^ McSherry 2010, p. 107.

- ^ McSherry 2010, p. 111.

- ^ Greg Grandin (2011). The Last Colonial Massacre: Latin America in the Cold War Archived 29 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine. University of Chicago Press. p. 75 Archived 22 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 9780226306902.

- ^ Walter L. Hixson (2009). The Myth of American Diplomacy: National Identity and U.S. Foreign Policy Archived 24 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Yale University Press. p. 223. ISBN 0300151314.

- ^ Maxwell, Kenneth (2004). "The Case of the Missing Letter in Foreign Affairs: Kissinger, Pinochet and Operation Condor". David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS), Harvard University.

- ^ Dalenogare Neto, Waldemar (30 March 2020). Os Estados Unidos e a Operação Condor (Doctoral thesis). Archived from the original on 5 May 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ McSherry, J. Patrice (1999). "Operation Condor: Clandestine Inter-American System". Social Justice. 26 (4 (78)): 144–174. ISSN 1043-1578. JSTOR 29767180. Archived from the original on 5 May 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Bevins, Vincent (2020). The Jakarta Method: Washington's Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program that Shaped Our World. PublicAffairs. pp. 266–267. ISBN 978-1-5417-4240-6.

- ^ a b "Chile". Center for Justice and Accountability. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Argentine dictator Videla dies in prison at age 87 – National | Globalnews.ca". Global News. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Operation Condor". CELS. Archived from the original on 26 November 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d Tremlett, Giles (3 September 2020). "Operation Condor: the cold war conspiracy that terrorised South America". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 September 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Bevins, Vincent (2020). The Jakarta Method: Washington's Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program that Shaped Our World. PublicAffairs. pp. 200–206. ISBN 978-1-5417-4240-6.

- ^ Good, Aaron (2022). American Exception. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. pp. 231–232, 237. ISBN 978-1510769137.

- ^ Conde, Arturo (10 September 2021). "New movie explores global complicity in Argentina's 'dirty war'". NBC News. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ a b c J. Patrice McSherry (2002). "Tracking the Origins of a State Terror Network: Operation Condor". Latin American Perspectives. 29 (1): 36–60. doi:10.1177/0094582X0202900103. S2CID 145129079.

- ^ a b Bevins, Vincent (2020). The Jakarta Method: Washington's Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program that Shaped Our World. PublicAffairs. p. 305. ISBN 978-1-5417-4240-6.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:6was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:5was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Robinwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Argentine Military Believed U.S. Gave Go-ahead for Dirty War". nsarchive2.gwu.edu. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ Silva, Darío (7 February 2020). "¿Cuántos desaparecidos dejó la dictadura? La duda que alimenta la grieta argentina". Perfil (in Spanish). Argentina. Archived from the original on 14 February 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ Larry Rohter (24 January 2014). Exposing the Legacy of Operation Condor Archived 1 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ McSherry 2010, pp. 107–124.

- ^ "Operación Cóndor en el Archivo del Terror". nsarchive2.gwu.edu. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ "A Brief Look at "Operation Condor"" (PDF). nsarchive2.gwu.edu. 22 August 1978. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ McSherry 2005, pp. 1–4.

- ^ "El Estado de necesidad" Archived 2 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish); Documents of the Trial of the Juntas at Desaparecidos.org.

- ^ "Argentina's Dirty War – Alicia Patterson Foundation". aliciapatterson.org. Archived from the original on 29 January 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ McSherry 2005, p. 4.

- ^ McSherry 2010, p. 108.

- ^ McSherry 2005.

- ^ a b "Operation Condor: the cold war conspiracy that terrorized South America". the Guardian. 3 September 2020. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Townley, Michael (25 November 2023). "Townley Papers, "Relato de Sucesos en la Muerte de Orlando Letelier el 21 de Septiembre, 1976 [Report of Events in the Death of Orlando Letelier, September 21, 1976]," March 14, 1976". National Security Archive. Archived from the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- ^ J. Patrice McSherry (2002). "Tracking the Origins of a State Terror Network: Operation Condor". Latin American Perspectives. 29 (1): 36–60. doi:10.1177/0094582X0202900103. S2CID 145129079.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search