Back अमेरिका केरौ खोज ANP استيطان الأمريكيتين Arabic Poblamientu d'América AST Poblament d'Amèrica Catalan Amerikas bosættelse Danish Besiedlung Amerikas German Alveno de la homo en Amerikon Esperanto Poblamiento de América Spanish Gizakien iritsiera Amerikara Basque Intiaanien alkuperä Finnish

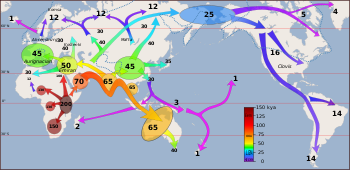

The peopling of the Americas began when Paleolithic hunter-gatherers (Paleo-Indians) entered North America from the North Asian Mammoth steppe via the Beringia land bridge, which had formed between northeastern Siberia and western Alaska due to the lowering of sea level during the Last Glacial Maximum (26,000 to 19,000 years ago).[2] These populations expanded south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet and spread rapidly southward, occupying both North and South America, by 12,000 to 14,000 years ago.[3][4][5][6][7] The earliest populations in the Americas, before roughly 10,000 years ago, are known as Paleo-Indians. Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been linked to Siberian populations by linguistic factors, the distribution of blood types, and in genetic composition as reflected by molecular data, such as DNA.[8][9]

While there is general agreement that the Americas were first settled from Asia, the pattern of migration and the place(s) of origin in Eurasia of the peoples who migrated to the Americas remain unclear.[4] The traditional theory is that Ancient Beringians moved when sea levels were significantly lowered due to the Quaternary glaciation,[10][11] following herds of now-extinct Pleistocene megafauna along ice-free corridors that stretched between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.[12] Another route proposed is that, either on foot or using primitive boats, they migrated down the Pacific coast to South America as far as Chile.[13] Any archaeological evidence of coastal occupation during the last Ice Age would now have been covered by the sea level rise, up to a hundred metres since then.[14]

The precise date for the peopling of the Americas is a long-standing open question, and while advances in archaeology, Pleistocene geology, physical anthropology, and DNA analysis have progressively shed more light on the subject, significant questions remain unresolved.[15][16] The "Clovis first theory" refers to the hypothesis that the Clovis culture represents the earliest human presence in the Americas about 13,000 years ago.[17] Evidence of pre-Clovis cultures has accumulated and pushed back the possible date of the first peopling of the Americas.[18][19][20][21] Academics generally believe that humans reached North America south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet at some point between 15,000 and 20,000 years ago.[15][18][22][23][24][25] Some new controversial archaeological evidence suggests the possibility that human arrival in the Americas may have occurred prior to the Last Glacial Maximum more than 20,000 years ago.[18][26][27][28][29]

- ^ Burenhult, Göran (2000). Die ersten Menschen. Weltbild Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8289-0741-6.

- ^ Pringle, Heather (March 8, 2017). "What Happens When an Archaeologist Challenges Mainstream Scientific Thinking?". Smithsonian.

- ^ Fagan, Brian M. & Durrani, Nadia (2016). World Prehistory: A Brief Introduction. Routledge. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-317-34244-1.

- ^ a b Goebel, Ted; Waters, Michael R.; O'Rourke, Dennis H. (2008). "The Late Pleistocene dispersal of modern humans in the Americas" (PDF). Science. 319 (5869): 1497–1502. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1497G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.398.9315. doi:10.1126/science.1153569. PMID 18339930. S2CID 36149744. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-02. Retrieved 2010-02-05.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (January 3, 2018). "In the Bones of a Buried Child, Signs of a Massive Human Migration to the Americas". The New York Times. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ Moreno-Mayar, JV; Potter, BA; Vinner, L; et al. (2018). "Terminal Pleistocene Alaskan genome reveals first founding population of Native Americans" (PDF). Nature. 553 (7687): 203–207. Bibcode:2018Natur.553..203M. doi:10.1038/nature25173. PMID 29323294. S2CID 4454580.

- ^ Núñez Castillo, Mélida Inés (2021-12-20). Ancient genetic landscape of archaeological human remains from Panama, South America and Oceania described through STR genotype frequencies and mitochondrial DNA sequences. Dissertation (doctoralThesis). doi:10.53846/goediss-9012. S2CID 247052631.

- ^ Ash, Patricia J. & Robinson, David J. (2011). The Emergence of Humans: An Exploration of the Evolutionary Timeline. John Wiley & Sons. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-119-96424-7.

- ^ Roberts, Alice (2010). The Incredible Human Journey. A&C Black. pp. 101–103. ISBN 978-1-4088-1091-0.

- ^ Fitzhugh, Drs. William; Goddard, Ives; Ousley, Steve; Owsley, Doug; Stanford, Dennis. "Paleoamerican". Smithsonian Institution Anthropology Outreach Office. Archived from the original on 2009-01-05. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ^ "Atlas of the Human Journey-The Genographic Project". National Geographic Society. 1996–2008. Archived from the original on 2011-05-01. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- ^ "The peopling of the Americas: Genetic ancestry influences health". Scientific American. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- ^ Fladmark, K. R. (1979). "Alternate Migration Corridors for Early Man in North America". American Antiquity. 44 (1): 55–69. doi:10.2307/279189. JSTOR 279189. S2CID 162243347.

- ^ "68 Responses to "Sea will rise 'to levels of last Ice Age'"". Center for Climate Systems Research, Columbia University. 26 January 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ a b Null (2022-06-27). "Peopling of the Americas". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Retrieved 2022-12-19.

- ^ Waguespack, Nicole (2012). "Early Paleoindians, from Colonization to Folsom". In Timothy R. Pauketat (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of North American Archaeology. Oxford University Press. pp. 86–95. ISBN 978-0-19-538011-8.

- ^ Surovell, T. A.; Allaun, S. A.; Gingerich, J. A. M.; Graf, K. E.; Holmes, C. D. (2022). "Late Date of human arrival to North America". PLOS ONE. 17 (4): e0264092. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264092. PMC 9020715. PMID 35442993.

- ^ a b c Yasinski, Emma (2022-05-02). "New Evidence Complicates the Story of the Peopling of the Americas". The Scientist Magazine. Retrieved 2022-12-19.

- ^ Ardelean, Ciprian F.; Becerra-Valdivia, Lorena; Pedersen, Mikkel Winther; Schwenninger, Jean-Luc; Oviatt, Charles G.; Macías-Quintero, Juan I.; Arroyo-Cabrales, Joaquin; Sikora, Martin; Ocampo-Díaz, Yam Zul E.; Rubio-Cisneros, Igor I.; Watling, Jennifer G.; De Medeiros, Vanda B.; De Oliveira, Paulo E.; Barba-Pingarón, Luis; Ortiz-Butrón, Agustín; Blancas-Vázquez, Jorge; Rivera-González, Irán; Solís-Rosales, Corina; Rodríguez-Ceja, María; Gandy, Devlin A.; Navarro-Gutierrez, Zamara; de la Rosa-Díaz, Jesús J.; Huerta-Arellano, Vladimir; Marroquín-Fernández, Marco B.; Martínez-Riojas, L. Martin; López-Jiménez, Alejandro; Higham, Thomas; Willerslev, Eske (2020). "Evidence of human occupation in Mexico around the Last Glacial Maximum". Nature. 584 (7819): 87–92. Bibcode:2020Natur.584...87A. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2509-0. PMID 32699412. S2CID 220697089.

- ^ Becerra-Valdivia, Lorena; Higham, Thomas (2020). "The timing and effect of the earliest human arrivals in North America". Nature. 584 (7819): 93–97. Bibcode:2020Natur.584...93B. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2491-6. PMID 32699413. S2CID 220715918.

- ^ Gruhn, Ruth (22 July 2020). "Evidence grows that peopling of the Americas began more than 20,000 years ago". Nature. 584 (7819): 47–48. Bibcode:2020Natur.584...47G. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02137-3. PMID 32699366. S2CID 220717778.

- ^ Spencer Wells (2006). Deep Ancestry: Inside the Genographic Project. National Geographic Books. pp. 222–. ISBN 978-0-7922-6215-2. OCLC 1031966951.

- ^ John H. Relethford (17 January 2017). 50 Great Myths of Human Evolution: Understanding Misconceptions about Our Origins. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 192–. ISBN 978-0-470-67391-1. OCLC 1238190784.

- ^ H. James Birx, ed. (10 June 2010). 21st Century Anthropology: A Reference Handbook. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4522-6630-5. OCLC 1102541304.

- ^ John E Kicza; Rebecca Horn (3 November 2016). Resilient Cultures: America's Native Peoples Confront European Colonialization 1500-1800 (2 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-50987-7.

- ^ Baisas, Laura (November 16, 2022). "Scientists still are figuring out how to age the ancient footprints in White Sands National Park". Popular Science. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ Somerville, Andrew D.; Casar, Isabel; Arroyo-Cabrales, Joaquín (2021). "New AMS Radiocarbon Ages from the Preceramic Levels of Coxcatlan Cave, Puebla, Mexico: A Pleistocene Occupation of the Tehuacan Valley?". Latin American Antiquity. 32 (3): 612–626. doi:10.1017/laq.2021.26.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Chatterswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Gibbon, Guy E 1998was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search