Back Cherokees Afrikaans ጻላጊኛ Amharic Ceroke sprǣc ANG شيروكي (لغة) Arabic شيروكى ARZ Idioma cheroqui AST چروکی دیلی AZB Cherokee (Sproch) BAR Чэрокі (мова) Byelorussian Черокски език Bulgarian

| Cherokee | |

|---|---|

| Southern Iroquoian | |

| ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ Tsalagi Gawonihisdi | |

Tsa-la-gi written in the Cherokee syllabary | |

| Pronunciation | Cherokee pronunciation: [dʒalaˈɡî ɡawónihisˈdî] |

| Native to | North America |

| Region | Eastern Oklahoma; Great Smoky Mountains[1] and Qualla Boundary in North Carolina.[2] Also in Arkansas,[3] and Cherokee community in California. |

| Ethnicity | Cherokee |

Native speakers | 1520 to ~2100 (2018 and 2019)[4][5] |

Iroquoian

| |

| Cherokee syllabary, Latin script | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina, Cherokee Nation[6][7][8][9] of Oklahoma |

| Regulated by | United Keetoowah Band Department of Language, History, & Culture[7][8] Council of the Cherokee Nation |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | chr |

| ISO 639-3 | chr |

| Glottolog | cher1273 |

| ELP | ᏣᎳᎩ (Cherokee) |

| Linguasphere | 63-AB |

Pre-contact distribution of the Cherokee language | |

Current geographic distribution of the Cherokee language | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Cherokee language |

|---|

|

ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ Tsalagi Gawonihisdi |

| History |

| Grammar |

| Writing System |

| Phonology |

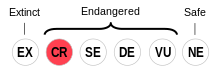

Cherokee or Tsalagi (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ, romanized: Tsalagi Gawonihisdi, IPA: [dʒalaˈɡî ɡawónihisˈdî]) is an endangered-to-moribund[a] Iroquoian language[4] and the native language of the Cherokee people.[6][7][8] Ethnologue states that there were 1,520 Cherokee speakers out of 376,000 Cherokees in 2018,[4] while a tally by the three Cherokee tribes in 2019 recorded about 2,100 speakers.[5] The number of speakers is in decline. The Tahlequah Daily Press reported in 2019 that most speakers are elderly, about eight fluent speakers die each month, and that only 5 people under the age of 50 are fluent.[11] The dialect of Cherokee in Oklahoma is "definitely endangered", and the one in North Carolina is "severely endangered" according to UNESCO.[12] The Lower dialect, formerly spoken on the South Carolina–Georgia border, has been extinct since about 1900.[13] The dire situation regarding the future of the two remaining dialects prompted the Tri-Council of Cherokee tribes to declare a state of emergency in June 2019, with a call to enhance revitalization efforts.[5]

Around 200 speakers of the Eastern (also referred to as the Middle or Kituwah) dialect remain in North Carolina, and language preservation efforts include the New Kituwah Academy, a bilingual immersion school.[14] The largest remaining group of Cherokee speakers is centered around Tahlequah, Oklahoma, where the Western (Overhill or Otali) dialect predominates. The Cherokee Immersion School (Tsalagi Tsunadeloquasdi) in Tahlequah serves children in federally recognized tribes from pre-school up to grade 6.[15]

Cherokee, a polysynthetic language,[16] is also the only member of the Southern Iroquoian family,[17] and it uses a unique syllabary writing system.[18] As a polysynthetic language, Cherokee differs dramatically from Indo-European languages such as English, French, Spanish, or Portuguese, and as such can be difficult for adult learners to acquire.[6] A single Cherokee word can convey ideas that would require multiple English words to express, from the context of the assertion and connotations about the speaker to the idea's action and its object. The morphological complexity of the Cherokee language is best exhibited in verbs, which comprise approximately 75% of the language, as opposed to only 25% of the English language.[6] Verbs must contain at minimum a pronominal prefix, a verb root, an aspect suffix, and a modal suffix.[19]

Extensive documentation of the language exists, as it is the indigenous language of North America in which the most literature has been published.[20] Such publications include a Cherokee dictionary and grammar, as well as several editions of the New Testament and Psalms of the Bible[21] and the Cherokee Phoenix (ᏣᎳᎩ ᏧᎴᎯᏌᏅᎯ, Tsalagi Tsulehisanvhi), the first newspaper published by Native Americans in the United States and the first published in a Native American language.[22][23]

- ^ Neely, Sharlotte (March 15, 2011). Snowbird Cherokees: People of Persistence. University of Georgia Press. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-0-8203-4074-6. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ Frey, Ben (2005). "A Look at the Cherokee Language" (PDF). Tar Heel Junior Historian. North Carolina Museum of History. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 7, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Cherokee". Endangered Languages Project. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Cherokee: A Language of the United States". Ethnologue. SIL International. 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c McKie, Scott (June 27, 2019). "Tri-Council declares State of Emergency for Cherokee language". Cherokee One Feather. Archived from the original on June 29, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "The Cherokee Nation & its Language". University of Minnesota: Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition. 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Keetoowah Cherokee is the Official Language of the UKB" (PDF). Keetoowah Cherokee News: Official Publication of the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma. April 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 15, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Language & Culture". United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians. Archived from the original on April 25, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ "UKB Constitution and By-Laws in the Keetoowah Cherokee Language" (PDF). United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- ^ "Language Status". Ethnologue. SIL International. 2019. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- ^ Ridge, Betty (April 11, 2019). "Cherokees strive to save a dying language". Tahlequah Daily Press. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

UNESCOwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Scancarelli 2005.

- ^ Schlemmer, Liz (October 28, 2018). "North Carolina Cherokee Say The Race To Save Their Language Is A Marathon". North Carolina Public Radio. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ Overall, Michael (February 7, 2018). "As first students graduate, Cherokee immersion program faces critical test: Will the language survive?". Tulsa World. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ Montgomery-Anderson, Brad (June 2008b). "Citing Verbs in Polysynthetic Languages: The Case of the Cherokee-English Dictionary". Southwest Journal of Linguistics. 27. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ Feeling 1975, p. viii.

- ^ "Cherokee Syllabary". Omniglot. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ Feeling et al. 2003, p. 16.

- ^ "Native Languages of the Americas: Cherokee (Tsalagi)". Native Languages of the Americas. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Cherokee: A Language of the United States". Ethnologue. SIL International. 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ LeBeau, Patrick. Term Paper Resource Guide to American Indian History. Greenwoord. Westport, CT: 2009. p. 132.

- ^ Woods, Thomas E. Exploring American History: Penn, William – Serra, Junípero Cavendish. Tarrytown, NY: 2008. p. 829.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search