Back العوامل الخارجية Arabic Xarici təsir Azerbaijani Външен ефект (икономика) Bulgarian Externalitat Catalan Externalita Czech Eksternalitet Danish Externer Effekt German Εξωτερικότητα Greek Ekstera efiko Esperanto Externalidad Spanish

| Part of a series about |

| Environmental economics |

|---|

|

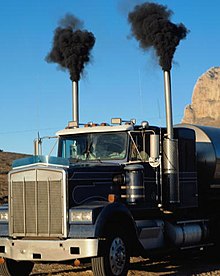

In economics, an externality or external cost is an indirect cost or benefit to an uninvolved third party that arises as an effect of another party's (or parties') activity. Externalities can be considered as unpriced components that are involved in either consumer or producer market transactions. Air pollution from motor vehicles is one example. The cost of air pollution to society is not paid by either the producers or users of motorized transport to the rest of society. Water pollution from mills and factories is another example. All (water) consumers are made worse off by pollution but are not compensated by the market for this damage. A positive externality is when an individual's consumption in a market increases the well-being of others, but the individual does not charge the third party for the benefit. The third party is essentially getting a free product. An example of this might be the apartment above a bakery receiving some free heat in winter. The people who live in the apartment do not compensate the bakery for this benefit.[1]

The concept of externality was first developed by Alfred Marshall in the 1890s[2] and achieved broader attention in the works of economist Arthur Pigou in the 1920s.[3] The prototypical example of a negative externality is environmental pollution. Pigou argued that a tax, equal to the marginal damage or marginal external cost, (later called a "Pigouvian tax") on negative externalities could be used to reduce their incidence to an efficient level.[3] Subsequent thinkers have debated whether it is preferable to tax or to regulate negative externalities,[4] the optimally efficient level of the Pigouvian taxation,[5] and what factors cause or exacerbate negative externalities, such as providing investors in corporations with limited liability for harms committed by the corporation.[6][7][8]

Externalities often occur when the production or consumption of a product or service's private price equilibrium cannot reflect the true costs or benefits of that product or service for society as a whole.[9][10] This causes the externality competitive equilibrium to not adhere to the condition of Pareto optimality. Thus, since resources can be better allocated, externalities are an example of market failure.[11]

Externalities can be either positive or negative. Governments and institutions often take actions to internalize externalities, thus market-priced transactions can incorporate all the benefits and costs associated with transactions between economic agents.[12][13] The most common way this is done is by imposing taxes on the producers of this externality. This is usually done similar to a quote where there is no tax imposed and then once the externality reaches a certain point there is a very high tax imposed. However, since regulators do not always have all the information on the externality it can be difficult to impose the right tax. Once the externality is internalized through imposing a tax the competitive equilibrium is now Pareto optimal.

- ^ Gruber, J. (2018). Public Finance & Public Policy

- ^ Boudreaux, Donald J.; Meiners, Roger (2019). "Externality: Origins and Classifications". Natural Resources Journal. 59 (1): 1–34. ISSN 0028-0739.

- ^ a b Pigou, Arthur Cecil (2017-10-24), "Welfare and Economic Welfare", The Economics of Welfare, Routledge, pp. 3–22, doi:10.4324/9781351304368-1, ISBN 978-1-351-30436-8, retrieved 2020-11-03

- ^ Kolstad, Charles D.; Ulen, Thomas S.; Johnson, Gary V. (2018-01-12), "Ex Post Liability for Harm vs. Ex Ante Safety Regulation: Substitutes or Complements?", The Theory and Practice of Command and Control in Environmental Policy, Routledge, pp. 331–344, doi:10.4324/9781315197296-16, ISBN 978-1-315-19729-6, retrieved 2020-11-03

- ^ Kaplow, Louis (May 2012). "Optimal Control of Externalities in the Presence of Income Taxation" (PDF). International Economic Review. 53 (2): 487–509. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2354.2012.00689.x. ISSN 0020-6598. S2CID 33103243.

- ^ Sim, Michael (2018). "Limited Liability and the Known Unknown". Duke Law Journal. 68: 275–332. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3121519. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 44186028 – via SSRN.

- ^ Hansmann, Henry; Kraakman, Reinier (May 1991). "Toward Unlimited Shareholder Liability for Corporate Torts". The Yale Law Journal. 100 (7): 1879. doi:10.2307/796812. ISSN 0044-0094. JSTOR 796812.

- ^ Buchanan, James; Wm. Craig Stubblebine (November 1962). "Externality". Economica. 29 (116): 371–84. doi:10.2307/2551386. JSTOR 2551386.

- ^ Mankiw, Nicholas (1998). Principios de Economía (Principles of Economics). Santa Fe: Cengage Learning. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-607-481-829-1.

- ^ "How do externalities affect equilibrium and create market failure?". investopedia.

- ^ Gruber, Jonathan. Public Finance and Public Policy (6th ed.). Worth Publishers. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-319-20584-3.

- ^ Stewart, Frances; Ghani, Ejaz (June 1991). "How significant are externalities for development?". World Development. 19 (6): 569–594. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(91)90195-N.

- ^ Jaeger, William. Environmental Economics for Tree Huggers and Other Skeptics, p. 80 (Island Press 2012): "Economists often say that externalities need to be 'internalized,' meaning that some action needs to be taken to correct this kind of market failure."

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search