Back الإصلاح البوهيمي Arabic Reforma bohèmia Catalan Česká reformace Czech Y Diwygiad Bohemaidd Welsh Reforma bohemia Spanish Չեխական ռեֆորմացիա Armenian 보헤미아 종교개혁 Korean Reformatio Bohemica Latin Češka reformacija Serbo-Croatian Реформація в Чехії Ukrainian

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

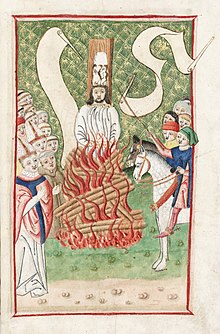

The Bohemian Reformation (also known as the Czech Reformation[1] or Hussite Reformation), preceding the Reformation of the 16th century, was a Christian movement in the late medieval and early modern Kingdom and Crown of Bohemia (mostly what is now present-day Czech Republic, Silesia, and Lusatia) striving for a reform of the Catholic Church. Lasting for more than 200 years, it had a significant impact on the historical development of Central Europe and is considered one of the most important religious, social, intellectual and political movements of the early modern period. The Bohemian Reformation produced the first national church separate from Roman authority in the history of Western Christianity, the first apocalyptic religious movement of the early modern period, and the first pacifist Protestant church.[1]

The Bohemian Reformation included several theological strains that developed over time.[2] Although it split into many groups, some characteristics were shared by all of them – communion under both kinds, distaste for the wealth and power of the church, emphasis on the Bible preached in a vernacular language and on an immediate relationship between man and God.[3][4] The Bohemian Reformation included particularly the efforts to reform the church before Hus, the Hussite movement (including e.g. Taborites and Orebites), the Unity of the Brethren and Utraquists or Calixtines.

Together with the Waldensians, Arnoldists and the Lollards (led by John Wycliffe), the Bohemian Reformation's Hussite movement is considered to be the precursor to the Protestant Reformation. These movements are sometimes referred to as the First Reformation in the Czech historiography.[5]

The Bohemian Reformation remained distinct from the German and Swiss Reformations despite their influence, although many Czech Utraquists grew closer and closer to the Lutherans. The Bohemian Reformation kept its own development until the suppression of the Bohemian Revolt in 1620. The victorious restored King Ferdinand II decided to force every inhabitant of Bohemia and Moravia to become Roman Catholic in accordance with the principle cuius regio, eius religio of the Peace of Augsburg (1555). The Bohemian Reformation ended up being diffused in the Protestant world and gradually lost its distinctiveness.[6] The Patent of Toleration issued in 1781 by Emperor Joseph II made Lutheran, Calvinist and Eastern Orthodox faiths legal in his realm but did not go so far as general religious toleration.[2] Despite the eradication of the Bohemian Reformation as a distinctive Christian movement, its tradition survived. Many churches (not only in the Czech Republic) remember their legacy, refer to the Bohemian Reformation and try to continue its tradition,[6] e. g. the Moravian Church (the continuator of the scattered Unity of the Brethren), Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren (Českobratrská církev evangelická), Czechoslovak Hussite Church (Československá církev husitská), Church of Brethren (Církev bratrská), Unity of Brethren Baptists (Bratrská jednota baptistů) and other denominations.[7]

- ^ a b Atwood, Craig D. "Czech Reformation and Hussite Revolution". www.oxfordbibliographies.com. Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Kruh českých duchovních tradic". veritas.evangnet.cz (in Czech). VERITAS – historická společnost pro aktualizaci odkazu české reformace. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ Soukup, Miroslav (2005). "Cesta k české reformaci" (PDF) (in Czech). Ústí nad Labem. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Turistická cesta valdenské a české reformace" (PDF) (in Czech). Veritas. 2005. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ Morée, Peter C. A. (2011). "Česká reformace u nás v cizině". www.christnet.eu (in Czech). Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ a b Nodl, Martin (2010). "Summary". In Horníčková, Kateřina; Šroněk, Michal (eds.). Umění české reformace (1380–1620) [The Art of the Bohemian Reformation (1380–1620)]. Praha: Academia. pp. 530–531. ISBN 978-80-200-1879-3.

- ^ Just, Jiří (2013). "Die Kralitzer Bibel". In Bahlcke, Joachim; Rohdewald, Stefan; Wünsch, Thomas (eds.). Religiöse Erinnerungsorte in Ostmitteleuropa: Konstitution und Konkurrenz im nationen- und epochenübergreifenden Zugriff. Akademie Verlag. p. 367. ISBN 978-3-05-009343-7.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search