Back Borskanker Afrikaans سرطان الثدي Arabic سرطان الثدى ARZ স্তন কেন্সাৰ Assamese Cáncanu de mama AST Süd vəzi xərçəngi Azerbaijani دؤش سرطانی AZB Krūtėis viežīs BAT-SMG Рак малочнай залозы Byelorussian Рак малочнай залозы BE-X-OLD

| Breast cancer | |

|---|---|

| |

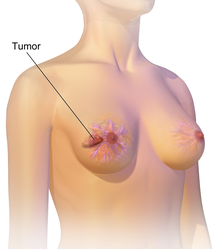

| An illustration of breast cancer | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | A lump in a breast, a change in breast shape, dimpling of the skin, fluid from the nipple, a newly inverted nipple, a red scaly patch of skin on the breast[1] |

| Risk factors | Being female, obesity, lack of exercise, alcohol, hormone replacement therapy during menopause, ionizing radiation, early age at first menstruation, having children late in life or not at all, older age, prior breast cancer, family history of breast cancer, Klinefelter syndrome[1][2][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Tissue biopsy[1] Mammography |

| Treatment | Surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, targeted therapy[1] |

| Prognosis | Five-year survival rate is approximately 85% (US, UK)[4][5] |

| Frequency | 2.2 million affected (global, 2020)[6] |

| Deaths | 685,000 (global, 2020)[6] |

Breast cancer is a cancer that develops from breast tissue.[7] Signs of breast cancer may include a lump in the breast, a change in breast shape, dimpling of the skin, milk rejection, fluid coming from the nipple, a newly inverted nipple, or a red or scaly patch of skin.[1] In those with distant spread of the disease, there may be bone pain, swollen lymph nodes, shortness of breath, or yellow skin.[8]

Risk factors for developing breast cancer include obesity, a lack of physical exercise, alcohol consumption, hormone replacement therapy during menopause, ionizing radiation, an early age at first menstruation, having children late in life (or not at all), older age, having a prior history of breast cancer, and a family history of breast cancer.[1][2][9] About five to ten percent of cases are the result of an inherited genetic predisposition,[1] including BRCA mutations among others.[1] Breast cancer most commonly develops in cells from the lining of milk ducts and the lobules that supply these ducts with milk.[1] Cancers developing from the ducts are known as ductal carcinomas, while those developing from lobules are known as lobular carcinomas.[1] There are more than 18 other sub-types of breast cancer.[2] Some, such as ductal carcinoma in situ, develop from pre-invasive lesions.[2] The diagnosis of breast cancer is confirmed by taking a biopsy of the concerning tissue.[1] Once the diagnosis is made, further tests are carried out to determine if the cancer has spread beyond the breast and which treatments are most likely to be effective.[1]

The balance of benefits versus harms of breast cancer screening is controversial. A 2013 Cochrane review found that it was unclear whether mammographic screening does more harm than good, in that a large proportion of women who test positive turn out not to have the disease.[10] A 2009 review for the US Preventive Services Task Force found evidence of benefit in those 40 to 70 years of age,[11] and the organization recommends screening every two years in women 50 to 74 years of age.[12] The medications tamoxifen or raloxifene may be used in an effort to prevent breast cancer in those who are at high risk of developing it.[2] Surgical removal of both breasts is another preventive measure in some high risk women.[2] In those who have been diagnosed with cancer, a number of treatments may be used, including surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and targeted therapy.[1] Types of surgery vary from breast-conserving surgery to mastectomy.[13][14] Breast reconstruction may take place at the time of surgery or at a later date.[14] In those in whom the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, treatments are mostly aimed at improving quality of life and comfort.[14]

Outcomes for breast cancer vary depending on the cancer type, the extent of disease, and the person's age.[14] The five-year survival rates in England and the United States are between 80 and 90%.[15][4][5] In developing countries, five-year survival rates are lower.[2] Worldwide, breast cancer is the leading type of cancer in women, accounting for 25% of all cases.[16] In 2018, it resulted in two million new cases and 627,000 deaths.[17] It is more common in developed countries,[2] and is more than 100 times more common in women than in men,[15][18] For transgender individuals on gender-affirming hormone therapy, breast cancer is 5 times more common in cisgender women than in transgender men, and 46 times more common in transgender women than in cisgender men.[19]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Breast Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)". NCI. 23 May 2014. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.2. ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9.

- ^ "Klinefelter Syndrome". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 24 May 2007. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012.

- ^ a b "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Breast Cancer". NCI. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Cancer Survival in England: Patients Diagnosed 2007–2011 and Followed up to 2012" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. 29 October 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ a b Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. (May 2021). "Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 71 (3): 209–249. doi:10.3322/caac.21660. PMID 33538338. S2CID 231804598.

- ^ "Breast Cancer". NCI. January 1980. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ Saunders C, Jassal S (2009). Breast cancer (1. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. Chapter 13. ISBN 978-0-19-955869-8. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015.

- ^ Fakhri N, Chad MA, Lahkim M, Houari A, Dehbi H, Belmouden A, et al. (September 2022). "Risk factors for breast cancer in women: an update review". Medical Oncology. 39 (12): 197. doi:10.1007/s12032-022-01804-x. PMID 36071255. S2CID 252113509.

- ^ Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ (June 2013). "Screening for breast cancer with mammography". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (6): CD001877. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub5. PMC 6464778. PMID 23737396.

- ^ Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan B, Nygren P, et al. (November 2009). "Screening for Breast Cancer: Systematic Evidence Review Update for the US Preventive Services Task Force [Internet]". U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. PMID 20722173. Report No.: 10-05142-EF-1.

- ^ Siu AL (February 2016). "Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 164 (4): 279–96. doi:10.7326/M15-2886. PMID 26757170.

- ^ "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question". Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. American College of Surgeons. September 2013. Archived from the original on 27 October 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Breast Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)". NCI. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ a b "World Cancer Report" (PDF). International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 1.1. ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9.

- ^ Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (November 2018). "Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 68 (6): 394–424. doi:10.3322/caac.21492. PMID 30207593. S2CID 52188256.

- ^ "Male Breast Cancer Treatment". Cancer.gov. 2014. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ "Breast Cancer Screening Guidelines for Transgender People".

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search