Back Serviks Afrikaans عنق الرحم Arabic Шыйка маткі Byelorussian Маточна шийка Bulgarian জরায়ুমুখ Bengali/Bangla Grlić materice BS Coll uterí Catalan Děložní hrdlo Czech Ceg y groth Welsh Livmoderhals Danish

| Cervix | |

|---|---|

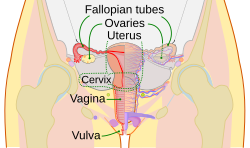

The human female reproductive system. The cervix is the lower narrower portion of the uterus. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Müllerian duct |

| Artery | Vaginal artery and uterine artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cervix uteri |

| MeSH | D002584 |

| TA98 | A09.1.03.010 |

| TA2 | 3508 |

| FMA | 17740 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The cervix (pl.: cervices) or cervix uteri is a dynamic fibromuscular organ of the female reproductive system that connects the vagina with the uterine cavity.[1] The human cervix has been documented anatomically since at least the time of Hippocrates, over 2,000 years ago[citation needed]. The cervix is approximately 4 cm long with a diameter of approximately 3 cm and tends to be described as a cylindrical shape, although the front and back walls of the cervix are contiguous.[1] The size of the cervix changes throughout a women's life cycle. For example, during their fertile years of the reproductive cycle, females tend to have a larger cervix vis á vis postmenopausal females; likewise, females who have produced offspring have a larger sized cervix than females who have not produced offspring.[1]

In relation to the vagina, the positioning of the cervix that opens into the uterus is called the internal os; and, the opening of the cervix in the vagina is called the external os.[1] The lower part of the cervix, known as the vaginal portion of the cervix (or ectocervix (cf. endocervix)), bulges into the top of the vagina[citation needed].

The conduit of the cervix, commonly referred to as the cervical canal, has at least two types of epithelia (lining): the endocervical lining is glandular epithelium that lines the endocervix with a single layer of column-shaped cells; and the ectocervical part of the conduit contains squamous epithelium.[1] Squamous epithelium line the conduit with multiple layers of cells topped with flat cells. These two linings converge at the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ). This junction changes location dynamically throughout a woman's life.[1] The two types of lining meet at the squamocolumnar junction which changes position also, throughout a woman's life.[1]

Cervical infections with the human papillomavirus (HPV) can cause changes in the epithelium, which can lead to cancer of the cervix. Cervical cytology tests can detect cervical cancer and its precursors, and enable early successful treatment. Ways to avoid HPV include avoiding heterosexual sex, utilising penile condoms, and receiving the HPV vaccination. HPV vaccines, developed in the early 21st century, reduce the risk of developing cervical cancer by preventing infections from the main cancer-causing strains of HPV.[2]

The conduit of the cervix describes the mechanics through which an egg cell permits sperm cells to fertilize it. Several methods of contraception aim to prevent fertilization by blocking this conduit, including cervical caps and cervical diaphragms, preventing the passage of sperm through the cervical canal. Other approaches aiming to prevent contraception include methods that observe cervical mucus, such as the Creighton Model and Billings method. Curvical mucus changes in consistency throughout women's menstrual periods, which may signal ovulation.

During vaginal childbirth, the cervix must flatten and dilate to allow the fetus to progress along the birth canal. Midwives and doctors use the extent of the dilation of the cervix to assist decision-making during childbirth.

- ^ a b c d e f g Prendiville, Walter; Sankaranarayanan, Rengaswamy (2017), "Anatomy of the uterine cervix and the transformation zone", Colposcopy and Treatment of Cervical Precancer, International Agency for Research on Cancer, retrieved 2024-03-29

- ^ "Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccines". National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. 29 December 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search