Back استقامة التطور Arabic Ortogenez Azerbaijani Progresivna evolucija BS Ortogènesi Catalan Orthogenese German Ortogénesis Spanish Ortogenees Estonian Ortogenesia Basque فرگشت هدفمند Persian Orthogenèse French

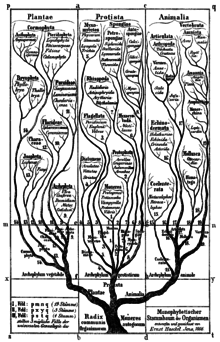

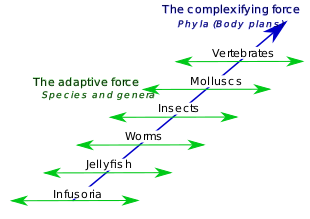

Orthogenesis, also known as orthogenetic evolution, progressive evolution, evolutionary progress, or progressionism, is an obsolete biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolve in a definite direction towards some goal (teleology) due to some internal mechanism or "driving force".[2][3][4] According to the theory, the largest-scale trends in evolution have an absolute goal such as increasing biological complexity. Prominent historical figures who have championed some form of evolutionary progress include Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and Henri Bergson.

The term orthogenesis was introduced by Wilhelm Haacke in 1893 and popularized by Theodor Eimer five years later. Proponents of orthogenesis had rejected the theory of natural selection as the organizing mechanism in evolution for a rectilinear (straight-line) model of directed evolution.[5] With the emergence of the modern synthesis, in which genetics was integrated with evolution, orthogenesis and other alternatives to Darwinism were largely abandoned by biologists, but the notion that evolution represents progress is still widely shared; modern supporters include E. O. Wilson and Simon Conway Morris. The evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr made the term effectively taboo in the journal Nature in 1948, by stating that it implied "some supernatural force".[6][7] The American paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson (1953) attacked orthogenesis, linking it with vitalism by describing it as "the mysterious inner force".[8] Despite this, many museum displays and textbook illustrations continue to give the impression that evolution is directed.

The philosopher of biology Michael Ruse notes that in popular culture, evolution and progress are synonyms, while the unintentionally misleading image of the March of Progress, from apes to modern humans, has been widely imitated.

- ^ Gould, Stephen J. (2001). The lying stones of Marrakech : penultimate reflections in natural history. Vintage. pp. 119–121. ISBN 978-0-09-928583-0.

- ^ Bowler 1989, pp. 268–270.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst (1988). Toward a New Philosophy of Biology: Observations of an Evolutionist. Harvard University Press. p. 499. ISBN 978-0-674-89666-6.

- ^ Ruse 1996, pp. 526–539.

- ^ Ulett, Mark A. (2014). "Making the case for orthogenesis: The popularization of definitely directed evolution (1890–1926)". Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 45: 124–132. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2013.11.009. PMID 24368232.

- ^ Ruse 1996, p. 447.

- ^ Letter from Ernst Mayr to R. H. Flower, Evolution papers, 23 January 1948

- ^ Simpson, George Gaylord (1953). Life of the Past: An Introduction to Paleontology. Yale University Press. p. 125.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search