Back Euripides Afrikaans Euripides ALS Euripides AN يوربيديس Arabic يوربيديس ARZ Eurípides AST Evripid Azerbaijani Еврипид Bashkir Эўрыпід Byelorussian Эўрыпід BE-X-OLD

Euripides | |

|---|---|

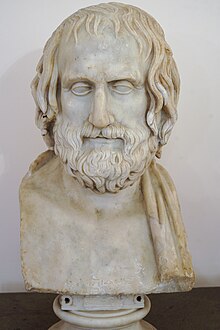

Bust of Euripides | |

| Born | c. 480 BC |

| Died | c. 406 BC (aged approximately 74) |

| Occupation | Playwright |

| Notable work |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Parent(s) | Mnesarchus Cleito |

Euripides[a] (c. 480 – c. 406 BC) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars attributed ninety-five plays to him, but the Suda says it was ninety-two at most. Of these, eighteen or nineteen have survived more or less complete (Rhesus is suspect).[3] There are many fragments (some substantial) of most of his other plays. More of his plays have survived intact than those of Aeschylus and Sophocles together, partly because his popularity grew as theirs declined[4][5]—he became, in the Hellenistic Age, a cornerstone of ancient literary education, along with Homer, Demosthenes, and Menander.[6]

Euripides is identified with theatrical innovations that have profoundly influenced drama down to modern times, especially in the representation of traditional, mythical heroes as ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. This new approach led him to pioneer developments that later writers adapted to comedy, some of which are characteristic of romance. He also became "the most tragic of poets",[nb 1] focusing on the inner lives and motives of his characters in a way previously unknown.[7][8] He was "the creator of ... that cage which is the theatre of Shakespeare's Othello, Racine's Phèdre, of Ibsen and Strindberg," in which "imprisoned men and women destroy each other by the intensity of their loves and hates".[9] But he was also the literary ancestor of comic dramatists as diverse as Menander and George Bernard Shaw.[10]

His contemporaries associated him with Socrates as a leader of a decadent intellectualism. Both were frequently lampooned by comic poets such as Aristophanes. Socrates was eventually put on trial and executed as a corrupting influence. Ancient biographies hold that Euripides chose a voluntary exile in old age, dying in Macedonia,[11] but recent scholarship casts doubt on these sources.

- ^ Jones, Daniel; Roach, Peter, James Hartman and Jane Setter, eds. Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary. 17th edition. Cambridge UP, 2006.

- ^ Nails 2002, p. 148.

- ^ Walton (1997, viii, xix)

- ^ B. Knox,'Euripides' in The Cambridge History of Classical Literature I: Greek Literature, P. Easterling and B. Knox (ed.s), Cambridge University Press (1985), p. 316

- ^ Moses Hadas, Ten Plays by Euripides, Bantam Classic (2006), Introduction, p. ix

- ^ L.P.E.Parker, Euripides: Alcestis, Oxford University Press (2007), Introduction p. lx

- ^ Moses Hadas, Ten Plays by Euripides, Bantam Classic (2006), Introduction, pp. xviii–xix

- ^ A.S. Owen, Euripides: Ion, Bristol Classical Press (1990), Introduction p. vii

- ^ B.M.Knox, 'Euripides' in The Cambridge History of Classical Literature I: Greek Literature, P. Easterling and B. Knox (ed.s), Cambridge University Press (1985), p. 329

- ^ Moses Hadas, Ten Plays by Euripides, Bantam Classic (2006), Introduction, pp. viii–ix

- ^ Denys L. Page, Euripides: Medea, Oxford University Press (1976), Introduction pp. ix–xii

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

Cite error: There are <ref group=nb> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=nb}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search