Back قابلية السكن لأنظمة الأقزام الحمراء Arabic Habitabilitat en sistemes de nanes roges Catalan Κατοικησιμότητα στα πλανητικά συστήματα των ερυθρών νάνων Greek Habitabilidad en sistemas de enanas rojas Spanish قابلیت سکونت سامانههای کوتوله قرمز Persian Punaisten kääpiötähtijärjestelmien elinkelpoisuus Finnish Abitabilità di un sistema planetario di una nana rossa Italian 赤色矮星系の居住可能性 Japanese 적색왜성계의 생명체 거주가능성 Korean Жизнепригодность системы красного карлика Russian

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

|

| This article is one of a series on: |

| Life in the universe |

|---|

| Outline |

| Planetary habitability in the Solar System |

| Life outside the Solar System |

| Habitability of... |

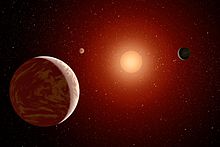

The theorized habitability of red dwarf systems is determined by a large number of factors. Modern evidence indicates that planets in red dwarf systems are unlikely to be habitable, due to their low stellar flux, high probability of tidal locking and thus likely lack of magnetospheres and atmospheres, small circumstellar habitable zones and the high stellar variation experienced by planets of red dwarf stars. However, the sheer numbers and longevity of red dwarfs could provide ample opportunity to realize any small possibility of habitability.

A major impediment to life developing in these systems is the intense tidal heating caused by the short distance of planets from their host red dwarfs.[1][2] Other tidal effects reduce the probability of life around red dwarfs, such as the extreme temperature differences created by one side of habitable-zone planets permanently facing the star, and the other perpetually turned away; and the lack of planetary axial tilts. Still, a planetary atmosphere may redistribute the heat, making temperatures more uniform.[3][2] Non-tidal factors further reduce the prospects for life in red-dwarf systems, such as extreme stellar variation, spectral energy distributions shifted to the infrared relative to the Sun (though a planetary magnetic field could protect from these flares) and small circumstellar habitable zones due to low light output.[2]

There are, however, a few factors that could increase the likelihood of life on red dwarf planets. Intense cloud formation on the star-facing side of a tidally locked planet may reduce overall thermal flux and drastically reduce equilibrium temperature differences between the two sides of the planet.[4] In addition, the sheer number of red dwarfs statistically increases the probability that there might exist habitable planets orbiting some of them. Red dwarfs account for about 85% of stars in the Milky Way[5][6] and the vast majority of stars in spiral and elliptical galaxies. There are expected to be tens of billions of super-Earth planets in the habitable zones of red dwarf stars in the Milky Way.[7]

M-type stars are also considered possible hosts of habitable exoplanets, even those with flares such as Proxima b. Determining the habitability of red dwarf stars could help determine how common life in the universe might be, as red dwarfs make up between 70% and 90% of all the stars in the galaxy. However, it is important to bear in mind that flare stars could greatly reduce the habitability of exoplanets by eroding their atmosphere.[8]

- ^ Barnes, Rory; Mullins, Kristina; Goldblatt, Colin; Meadows, Victoria S.; Kasting, James F.; Heller, René (March 2013). "Tidal Venuses: Triggering a Climate Catastrophe via Tidal Heating". Astrobiology. 13 (3): 225–250. arXiv:1203.5104. Bibcode:2013AsBio..13..225B. doi:10.1089/ast.2012.0851. PMC 3612283. PMID 23537135.

- ^ a b c Major, Jason (23 December 2015). ""Tidal Venuses" May Have Been Wrung Out To Dry". Universetoday.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ Wilkins, Alasdair (2012-01-16). "Life might not be possible around red dwarf stars". Io9.com. Archived from the original on 2015-10-03. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- ^ Yang, J.; Cowan, N. B.; Abbot, D. S. (2013). "Stabilizing Cloud Feedback Dramatically Expands the Habitable Zone of Tidally Locked Planets". The Astrophysical Journal. 771 (2): L45. arXiv:1307.0515. Bibcode:2013ApJ...771L..45Y. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/771/2/L45. S2CID 14119086.

- ^ Than, Ker (2006-01-30). "Astronomers Had it Wrong: Most Stars are Single". Space.com. TechMediaNetwork. Archived from the original on 2019-09-24. Retrieved 2013-07-04.

- ^ Staff (2013-01-02). "100 Billion Alien Planets Fill Our Milky Way Galaxy: Study". Space.com. Archived from the original on 2020-05-09. Retrieved 2013-01-03.

- ^ Gilster, Paul (2012-03-29). "ESO: Habitable Red Dwarf Planets Abundant". Centauri-dreams.org. Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- ^ "Habitable Exoplanet Observatory (HabEx)". www.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-10-08. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search