Back New Horizons Afrikaans New Horizons ALS New Horizons AN نيو هورايزونز Arabic نيو هورايزنز ARZ নিউ হৰাইজন্ছ Assamese New Horizons AST Yeni üfüqlər Azerbaijani New Horizons Byelorussian Нови хоризонти Bulgarian

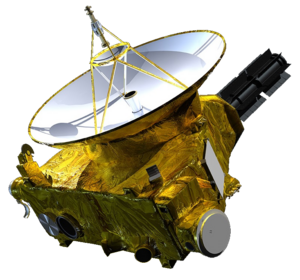

New Horizons space probe | |||||||||||||||||

| Mission type | Flyby (132524 APL · Jupiter · Pluto · 486958 Arrokoth) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operator | NASA | ||||||||||||||||

| COSPAR ID | 2006-001A | ||||||||||||||||

| SATCAT no. | 28928 | ||||||||||||||||

| Website | pluto science.nasa.gov/mission/new-horizons | ||||||||||||||||

| Mission duration | Primary mission: 9.5 years Elapsed: 18 years, 3 months, 9 days | ||||||||||||||||

| Spacecraft properties | |||||||||||||||||

| Manufacturer | APL / SwRI | ||||||||||||||||

| Launch mass | 478 kg (1,054 lb)[1] | ||||||||||||||||

| Dry mass | 401 kg (884 lb) | ||||||||||||||||

| Payload mass | 30.4 kg (67 lb) | ||||||||||||||||

| Dimensions | 2.2 × 2.1 × 2.7 m (7.2 × 6.9 × 8.9 ft) | ||||||||||||||||

| Power | 245 watts | ||||||||||||||||

| Start of mission | |||||||||||||||||

| Launch date | January 19, 2006, 19:00:00.221 UTC[2] | ||||||||||||||||

| Rocket | Atlas V (551) AV-010[2] + Star 48B 3rd stage | ||||||||||||||||

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral SLC-41 | ||||||||||||||||

| Contractor | International Launch Services[3] | ||||||||||||||||

| Orbital parameters | |||||||||||||||||

| Eccentricity | 1.41905 | ||||||||||||||||

| Inclination | 2.23014° | ||||||||||||||||

| Epoch | January 1, 2017 (JD 2457754.5)[4] | ||||||||||||||||

| Flyby of 132524 APL (incidental) | |||||||||||||||||

| Closest approach | June 13, 2006, 04:05 UTC | ||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 101,867 km (63,297 mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| Flyby of Jupiter (gravity assist) | |||||||||||||||||

| Closest approach | February 28, 2007, 05:43:40 UTC | ||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 2,300,000 km (1,400,000 mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| Flyby of Pluto | |||||||||||||||||

| Closest approach | July 14, 2015, 11:49:57 UTC | ||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 12,500 km (7,800 mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| Flyby of Charon (moon) | |||||||||||||||||

| Closest approach | July 14, 2015, 12:02:22 UTC | ||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 29,431 km (18,288 mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| Flyby of 486958 Arrokoth | |||||||||||||||||

| Closest approach | January 1, 2019, 05:33:00 UTC | ||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 3,500 km (2,200 mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

New Horizons is an interplanetary space probe launched as a part of NASA's New Frontiers program.[5] Engineered by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) and the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), with a team led by Alan Stern,[6] the spacecraft was launched in 2006 with the primary mission to perform a flyby study of the Pluto system in 2015, and a secondary mission to fly by and study one or more other Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) in the decade to follow, which became a mission to 486958 Arrokoth. It is the fifth space probe to achieve the escape velocity needed to leave the Solar System.

On January 19, 2006, New Horizons was launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station by an Atlas V rocket directly into an Earth-and-solar escape trajectory with a speed of about 16.26 km/s (10.10 mi/s; 58,500 km/h; 36,400 mph). It was the fastest (average speed with respect to Earth) human-made object ever launched from Earth.[7][8][9][10] It is not the fastest speed recorded for a spacecraft, which, as of 2023, is that of the Parker Solar Probe. After a brief encounter with asteroid 132524 APL, New Horizons proceeded to Jupiter, making its closest approach on February 28, 2007, at a distance of 2.3 million kilometers (1.4 million miles). The Jupiter flyby provided a gravity assist that increased New Horizons' speed; the flyby also enabled a general test of New Horizons' scientific capabilities, returning data about the planet's atmosphere, moons, and magnetosphere.

Most of the post-Jupiter voyage was spent in hibernation mode to preserve onboard systems, except for brief annual checkouts.[11] On December 6, 2014, New Horizons was brought back online for the Pluto encounter, and instrument check-out began.[12] On January 15, 2015, the spacecraft began its approach phase to Pluto.

On July 14, 2015, at 11:49 UTC, it flew 12,500 km (7,800 mi) above the surface of Pluto,[13][14] which at the time was 34 AU from the Sun,[15] making it the first spacecraft to explore the dwarf planet.[16] In August 2016, New Horizons was reported to have traveled at speeds of more than 84,000 km/h (52,000 mph).[17] On October 25, 2016, at 21:48 UTC, the last recorded data from the Pluto flyby was received from New Horizons.[18] Having completed its flyby of Pluto,[19] New Horizons then maneuvered for a flyby of Kuiper belt object 486958 Arrokoth (then nicknamed Ultima Thule),[20][21][22] which occurred on January 1, 2019,[23][24] when it was 43.4 AU (6.49 billion km; 4.03 billion mi) from the Sun.[20][21] In August 2018, NASA cited results by Alice on New Horizons to confirm the existence of a "hydrogen wall" at the outer edges of the Solar System. This "wall" was first detected in 1992 by the two Voyager spacecraft.[25][26] NASA has announced it is to extend operations for New Horizons until the spacecraft exits the Kuiper Belt, which is expected to occur between 2028 and 2029.[27]

- ^ "New Horizons". NASA's Solar System Exploration website. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Cleary, Mark C. (August 2010). Evolved Expendable Launch Operations at Cape Canaveral, 2002–2009 (PDF) (Report). Air Force Space & Missile Museum. p. 30. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 3, 2020. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ "Atlas Launch Archives". International Launch Services. Archived from the original on April 22, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ "HORIZONS Web-Interface". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2016. To find results, change Target Body to "New Horizons", Center to "@Sun", and Time Span to include "2017-01-01".

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (July 18, 2015). "The Long, Strange Trip to Pluto, and How NASA Nearly Missed It". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ Leo Laporte (August 31, 2015). "Alan Stern: principal investigator for New Horizons". TWiT.tv (Podcast). Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

APL-20070116was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

sciam20130225was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

ionine20150609was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Whitwam, Ryan (December 13, 2017). "New Horizons Space Probe Target May Have its Own Tiny Moonlet – ExtremeTech". Ziff Davis. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ "New Horizons: NASA's Mission to Pluto". NASA. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ "New Horizons – News". Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. December 6, 2014. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (July 14, 2015). "NASA's New Horizons Spacecraft Completes Flyby of Pluto". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ^ Dunn, Marcia (July 14, 2015). "Pluto close-up: Spacecraft makes flyby of icy, mystery world". Excite. Associated Press (AP). Archived from the original on July 16, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ^ "New Horizons". NASA. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie; Buckley, Mike; Stotoff, Maria (July 14, 2015). "15-149 NASA's Three-Billion-Mile Journey to Pluto Reaches Historic Encounter". NASA. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ^ Cofield, Calia (August 24, 2016). "How We Could Visit the Possibly Earth-Like Planet Proxima b". Space.com. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (October 28, 2016). "No More Data From Pluto". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ Jayawardhana, Ray (December 11, 2015). "Give It Up for Pluto". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 10, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ a b Talbert, Tricia (August 28, 2015). "NASA's New Horizons Team Selects Potential Kuiper Belt Flyby Target". NASA. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Cofield, Calla (August 28, 2015). "Beyond Pluto: 2nd Target Chosen for New Horizons Probe". Space.com. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ Dunn, Marcia (October 22, 2015). "NASA's New Horizons on new post-Pluto mission". Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 28, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ Corum, Jomathan (February 10, 2019). "New Horizons Glimpses the Flattened Shape of Ultima Thule – NASA's New Horizons spacecraft flew past the most distant object ever visited: a tiny fragment of the early solar system known as 2014 MU69 and nicknamed Ultima Thule. – Interactive". The New York Times. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (December 31, 2018). "New Horizons Spacecraft Completes Flyby of Ultima Thule, the Most Distant Object Ever Visited". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 19, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ Gladstone, G. Randall; et al. (August 7, 2018). "The Lyman-α Sky Background as Observed by New Horizons". Geophysical Research Letters. 45 (16): 8022. arXiv:1808.00400. Bibcode:2018GeoRL..45.8022G. doi:10.1029/2018GL078808. S2CID 119395450.

- ^ Letzter, Rafi (August 9, 2018). "NASA Spotted a Vast, Glowing 'Hydrogen Wall' at the Edge of Our Solar System". Live Science. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ^ Talbert, Tricia (September 29, 2023). "NASA's New Horizons to Continue Exploring Outer Solar System". NASA. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search