Back Sanherib Afrikaans ሰናክሬም Amharic سنحاريب Arabic ܣܢܚܪܝܒ ARC سنحاريب ARZ Sennaxerib Azerbaijani سناخریب AZB Сінахерыб Byelorussian Сенахериб Bulgarian Sennàquerib Catalan

| Sennacherib | |

|---|---|

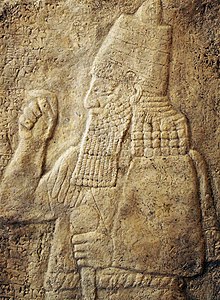

Cast of a rock relief of Sennacherib from the foot of Mount Judi, near Cizre | |

| King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire | |

| Reign | 705–681 BC |

| Predecessor | Sargon II |

| Successor | Esarhaddon |

| Born | c. 745 BC[1] Nimrud[2] (?) |

| Died | 20 October 681 BC (aged c. 64) Nineveh |

| Spouse | |

| Issue Among others | |

| Akkadian |

|

| Dynasty | Sargonid dynasty |

| Father | Sargon II |

| Mother | Ra'īmâ |

Sennacherib (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Sîn-ahhī-erība[3] or Sîn-aḥḥē-erība,[4] meaning "Sîn has replaced the brothers")[5][6][a] was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705 BC to his own death in 681 BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous Assyrian kings for the role he plays in the Hebrew Bible, which describes his campaign in the Levant. Other events of his reign include his destruction of the city of Babylon in 689 BC and his renovation and expansion of the last great Assyrian capital, Nineveh.

Sîn-ahhī-erība[3] or Sîn-aḥḥē-erība,[4] meaning "Sîn has replaced the brothers")[5][6][a] was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705 BC to his own death in 681 BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous Assyrian kings for the role he plays in the Hebrew Bible, which describes his campaign in the Levant. Other events of his reign include his destruction of the city of Babylon in 689 BC and his renovation and expansion of the last great Assyrian capital, Nineveh.

Although Sennacherib was one of the most powerful and wide-ranging Assyrian kings, he faced considerable difficulty in controlling Babylonia, which formed the southern portion of his empire. Many of Sennacherib's Babylonian troubles stemmed from the Chaldean[7] tribal chief Marduk-apla-iddina II, who had been Babylon's king until Sennacherib's father defeated him. Shortly after Sennacherib inherited the throne in 705 BC, Marduk-apla-iddina retook Babylon and allied with the Elamites. Though Sennacherib reclaimed the south in 700 BC, Marduk-apla-iddina continued to trouble him, probably instigating Assyrian vassals in the Levant to rebel, leading to the Levantine War of 701 BC, and himself warring against Bel-ibni, Sennacherib's vassal king in Babylonia.

After the Babylonians and Elamites captured and executed Sennacherib's eldest son Aššur-nādin-šumi, whom Sennacherib had proclaimed as his new vassal king in Babylon, Sennacherib campaigned in both regions, subduing Elam. Because Babylon, well within his own territory, had been the target of most of his military campaigns and had caused the death of his son, he destroyed the city in 689 BC.

In the Levantine War, the states in the southern Levant, especially the Kingdom of Judah under King Hezekiah, were not subdued as easily as those in the north. The Assyrians thus invaded Judah. Though the biblical narrative holds that divine intervention by an angel ended the Assyrian siege of Jerusalem by destroying the Assyrian army, an outright defeat is unlikely as Hezekiah submitted to Sennacherib at the end of the campaign.[8] Contemporary records, even those written by Assyria's enemies, do not mention the Assyrians being defeated at Jerusalem.[9]

Sennacherib transferred the capital of Assyria to Nineveh, where he had spent most of his time as crown prince. To transform Nineveh into a capital worthy of his empire, he launched one of the most ambitious building projects in ancient history. He expanded the size of the city and constructed great city walls, numerous temples and a royal garden. His most famous work in the city is the Southwest Palace, which Sennacherib named his "Palace without Rival".

After the death of his eldest son and crown prince Aššur-nādin-šumi, Sennacherib originally designated his second son Arda-Mulissu heir. He later replaced him with a younger son, Esarhaddon, in 684 BC, for unknown reasons. Sennacherib ignored Arda-Mulissu's repeated appeals to be reinstated as heir, and in 681 BC, Arda-Mulissu and his brother Nabu-shar-usur murdered Sennacherib,[b] hoping to seize power for themselves. Babylonia and the Levant welcomed his death as divine punishment, while the Assyrian heartland probably reacted with resentment and horror. Arda-Mulissu's coronation was postponed, and Esarhaddon raised an army and seized Nineveh, installing himself as king as intended by Sennacherib.

- ^ Elayi 2017, p. 29.

- ^ Elayi 2018, p. 18.

- ^ Harmanşah 2013, p. 120.

- ^ Kalimi 2014, p. 11.

- ^ "Sin-ahhe-eriba [SENNACHERIB, KING OF ASSYRIA] (RN)". Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus. University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ Elayi 2018, p. 12.

- ^ Frahm 2003, p. 129.

- ^ Kalimi 2014, p. 20.

- ^ Luckenbill 1924, p. 13.

- ^ Knapp 2020, p. 166.

- ^ Knapp 2020, p. 165.

- ^ Knapp 2020, pp. 167–181.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search