Back Antonio Negri Afrikaans أنطونيو نيجري Arabic انطونيو نيجرى ARZ Antonio Neqri Azerbaijani Антонио Негри Bulgarian Antonio Negri Catalan Antonio Negri Czech Antonio Negri Danish Antonio Negri German Αντόνιο Νέγκρι Greek

Antonio Negri | |

|---|---|

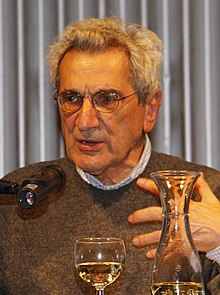

Negri in 2009 | |

| Born | 1 August 1933 Padua, Kingdom of Italy |

| Died | 16 December 2023 (aged 90) Paris, France |

| Alma mater | |

| Era | Contemporary philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Institutions | |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas |

|

| Part of a series about |

| Imperialism studies |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarian socialism |

|---|

|

Antonio Negri (1 August 1933 – 16 December 2023) was an Italian political philosopher known as one of the most prominent theorists of autonomism, as well as for his co-authorship of Empire with Michael Hardt and his work on the philosopher Baruch Spinoza.[9][10][11][12] Born in Padua, Italy, Negri became a professor of political philosophy at the University of Padua, where he taught state and constitutional theory.[13] Negri founded the Potere Operaio (Worker Power) group in 1969 and was a leading member of Autonomia Operaia, and published hugely influential books urging "revolutionary consciousness."

Negri was accused in the late 1970s of various charges including being the mastermind of the left-wing urban guerrilla organization Red Brigades (Brigate Rosse or BR),[14] which was involved in the May 1978 kidnapping and murder of former Italian prime minister Aldo Moro. On 7 April 1979, he Negri was arrested and charged with a long list of crimes including the Moro murder. Most charges were dropped quickly, but in 1984 he was still sentenced (in absentia) to 30 years in prison. He was given an additional four years on the charge of being "morally responsible" for the violence of political activists in the 1960s and 1970s.[15] The question of Negri's complicity with left-wing extremism is a controversial subject.[16] He was indicted on a number of charges, including "association and insurrection against the state" (a charge which was later dropped), and sentenced for involvement in two murders.

Negri fled to France where, protected by the Mitterrand doctrine, he taught at the Paris VIII (Vincennes) and the Collège international de philosophie, along with Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, and Gilles Deleuze. In 1997, after a plea-bargain that reduced his prison time from 30 to 13 years,[17] he returned to Italy to serve the end of his sentence. Many of his most influential books were published while he was behind bars. He hence lived in Venice and Paris with his partner, the French philosopher Judith Revel. He was the father of film director Anna Negri.

Like Deleuze, Negri's preoccupation with Spinoza is well known in contemporary philosophy.[18][19] Along with Althusser and Deleuze, he has been one of the central figures of a French-inspired neo-Spinozism in continental philosophy of the late 20th and early 21st centuries,[20][5][21][22][23] that was the second remarkable Spinoza revival in history, after a well-known rediscovery of Spinoza by German thinkers (especially the German Romantics and Idealists) in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

- ^ Negri, Antonio: The Savage Anomaly: The Power of Spinoza's Metaphysics and Politics. Translated from the Italian by Michael Hardt. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991). Originally published as L'anomalia selvaggia: Saggio su potere e potenza in Baruch Spinoza (Milano: Feltrinelli, 1981). Antonio Negri (1981): "This work [The Savage Anomaly] was written in prison. And it was also conceived, for the most part, in prison. Certainly, I have always known Spinoza well. Since I was in school, I have loved the Ethics (and here I would like to fondly remember my teacher of those years). I continued to work on it, never losing touch, but a full study required too much time. ... Spinoza is the clear and luminous side of Modern philosophy. ... With Spinoza, philosophy succeeds for the first time in negating itself as a science of mediation. In Spinoza there is the sense of a great anticipation of the future centuries; there is the intuition of such a radical truth of future philosophy that it not only keeps him from being flattened onto seventeenth-century thought but also, it often seems, denies any confrontation, any comparison. Really, none of his contemporaries understands him or refutes him. ... Spinoza's materialist metaphysics is the potent anomaly of the century: not a vanquished or marginal anomaly but, rather, an anomaly of victorious materialism, of the ontology of a being that always moves forward and that by constituting itself poses the ideal possibility for revolutionizing the world."

- ^ Toscano, Alberto (January 2005). "The Politics of Spinozism: Composition and Communication (Paper presented at the Cultural Research Bureau of Iran, Tehran, January 4, 2005)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Ruddick, Susan (2010), 'The Politics of Affect: Spinoza in the Work of Negri and Deleuze,'. Theory, Culture & Society 27(4): 21–45

- ^ Grattan, Sean (2011), 'The Indignant Multitude: Spinozist Marxism after Empire,'. Mediations 25(2): 7–8

- ^ a b Duffy, Simon B. (2014), 'French and Italian Spinozism,'. In: Rosi Braidotti (ed.), After Poststructuralism: Transitions and Transformations. (London: Routledge, 2014), p. 148–168

- ^ a b c Maggiori Robert, "Toni Negri, le retour du «diable» Archived 5 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine", Libération.fr, 3 July 1997.

- ^ Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, Empire (Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England: Harvard University Press, 2000), § 3.4.

- ^ Elsa Romeo, La Scuola di Croce: testimonianze sull'Istituto italiano per gli studi storici, Il Mulino, 1992, p. 309.

- ^ Negri, Antonio: L'anomalia selvaggia. Saggio su potere e potenza in Baruch Spinoza. (Milano: Feltrinelli, 1981)

- ^ Negri, Antonio: Spinoza sovversivo. Variazioni (in)attuali. (Roma: Antonio Pellicani Editore, 1992)

- ^ Negri, Antonio: Spinoza et nous [La philosophie en effet]. (Paris: Éditions Galilée, 2010)

- ^ Negri, Antonio: Spinoza e noi. (Milano: Mimesis, 2012)

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

portelliwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Oxford Reference. "Antonio Negri". Archived from the original on 5 April 2017.

- ^ Drake, Richard. "The Red and the Black: Terrorism in Contemporary Italy", International Political Science Review, Vol. 5, No. 3, Political Crises (1984), pp. 279–298. Quote: "The debate over Toni Negri's complicity in left-wing extremism has already resulted in the publication of several thick polemical volumes, as well as a huge number of op-ed pieces."

- ^ Windschuttle, Keith. "Tutorials in Terrorism", The Australian, 16 March 2005. [dead link]

- ^ Negri, Antonio: Subversive Spinoza: (Un)Contemporary Variations. Translated from the Italian by Timothy S. Murphy et al. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004). Originally published as Spinoza sovversivo: Variazioni (in)attuali (Roma: Antonio Pellicani Editore, 1992). Antonio Negri (1992): "Twenty-some years ago, when at the age of forty I returned to the study of the Ethics, which had been 'my book' during adolescence, the theoretical climate in which I found myself immersed had changed to such an extent that it was difficult to tell if the Spinoza standing before me then was the same one who had accompanied me in my earliest studies."

- ^ Žižek, Slavoj: The Parallax View. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006)

- ^ Several notable figures of French (and Italian)-inspired post-structuralist neo-Spinozism including Ferdinand Alquié, Louis Althusser, Étienne Balibar, Alain Billecoq, Francesco Cerrato, Paolo Cristofolini, Gilles Deleuze, Martial Gueroult, Chantal Jaquet, Frédéric Lordon, Pierre Macherey, Frédéric Manzini, Alexandre Matheron, Filippo Mignini, Pierre-François Moreau, Vittorio Morfino, Antonio Negri, Charles Ramond, Bernard Rousset, Pascal Sévérac, André Tosel, Lorenzo Vinciguerra, and Sylvain Zac.

- ^ Vinciguerra, Lorenzo (2009), 'Spinoza in French Philosophy Today,'. Philosophy Today 53(4): 422–437. doi:10.5840/philtoday200953410

- ^ Peden, Knox: Reason without Limits: Spinozism as Anti-Phenomenology in Twentieth-Century French Thought. (PhD thesis, University of California, Berkeley, 2009)

- ^ Peden, Knox: Spinoza Contra Phenomenology: French Rationalism from Cavaillès to Deleuze. (Stanford University Press, 2014) ISBN 9780804791342

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search