Back Argaïese mense Afrikaans إنسان بدائي Arabic Arxantroplar Azerbaijani Pradavni čovjek BS Homo arcaic Catalan Archaischer Homo sapiens German Αρχαϊκοί άνθρωποι Greek Humanos arcaicos Spanish انسان خردمند باستانی Persian Homo sapiens arcaico Galician

−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

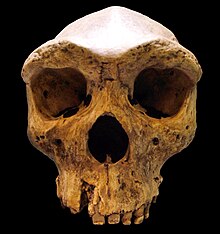

Archaic humans[a] is a broad category denoting all species of the genus Homo that are not Homo sapiens (which are known as modern humans). Among the earliest modern human remains are those from Jebel Irhoud in Morocco (about 315 ka), Florisbad in South Africa (259 ka),[1][2][3][4][5][6] and Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) in southern Ethiopia (c. 233 or 195 ka).[2][7] Some examples of archaic humans include H. antecessor (1200–770 ka), H. bodoensis (1200–300 ka), H. heidelbergensis (600–200 ka), Neanderthals (H. neanderthalensis; 430–40 ka),[8] H. rhodesiensis (300–125 ka) and Denisovans (H. denisova; 285–52 ka),

Most archaic humans had a brain size averaging 1,200 to 1,400 cubic centimeters, which overlaps with the range of modern humans. Notable exceptions include Homo naledi and Homo floresiensis, having cranial capacities of 465-610 and 380 cubic centimeters, respectively.

Archaic humans are distinguished from anatomically modern humans by having a thick skull, prominent supraorbital ridges (brow ridges) and the lack of a prominent chin.[9][10]

Anatomically modern humans appeared around 300,000 years ago in Africa,[4][5][6] and 70,000 years ago gradually supplanted the "archaic" human varieties. Non-modern varieties of Homo are certain to have survived until after 30,000 years ago, and perhaps until as recently as 12,000 years ago.[b] According to recent genetic studies, modern humans may have bred with two or more groups of archaic humans, including Neanderthals and Denisovans.[11] Other studies have cast doubt on admixture being the source of the shared genetic markers between archaic and modern humans, pointing to an ancestral origin of the traits which originated 500,000–800,000 years ago.[12][13][14] In August 2023, scientists reported the discovery of an unknown ancient human hominin that may have lived 300,000 years ago in China.[15][16]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Stringer, C. (2016). "The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1698): 20150237. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0237. PMC 4920294. PMID 27298468.

- ^ a b Hammond, Ashley S.; Royer, Danielle F.; Fleagle, John G. (Jul 2017). "The Omo-Kibish I pelvis". Journal of Human Evolution. 108: 199–219. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.04.004. ISSN 1095-8606. PMID 28552208.

- ^ White, Tim D.; Asfaw, B.; DeGusta, D.; Gilbert, H.; Richards, G. D.; Suwa, G.; Howell, F. C. (2003). "Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia". Nature. 423 (6491): 742–747. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..742W. doi:10.1038/nature01669. PMID 12802332. S2CID 4432091.

- ^ a b Callaway, Ewan (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species' history". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ a b Sample, Ian (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens bones ever found shake foundations of the human story". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ a b Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Ben-Ncer, Abdelouahed; Bailey, Shara E.; Freidline, Sarah E.; Neubauer, Simon; Skinner, Matthew M.; Bergmann, Inga; Le Cabec, Adeline; Benazzi, Stefano; Harvati, Katerina; Gunz, Philipp (2017). "New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens" (PDF). Nature. 546 (7657): 289–292. Bibcode:2017Natur.546..289H. doi:10.1038/nature22336. PMID 28593953. S2CID 256771372.

- ^ Vidal, Celine M.; Lane, Christine S.; Asfawrossen, Asrat; et al. (Jan 2022). "Age of the oldest known Homo sapiens from eastern Africa". Nature. 601 (7894): 579–583. Bibcode:2022Natur.601..579V. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04275-8. PMC 8791829. PMID 35022610.

- ^ Hublin, J. J. (2009). "The origin of Neandertals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (38): 16022–16027. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10616022H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0904119106. JSTOR 40485013. PMC 2752594. PMID 19805257.

- ^ Dawkins (2005). "Archaic homo sapiens". The Ancestor's Tale. Boston: Mariner. ISBN 978-0618619160.

- ^ Barker, Graeme (1999). Companion Encyclopedia of Archaeology. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415213295 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mitchell, Alanna (January 30, 2012). "DNA Turning Human Story Into a Tell-All". The New York Times. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- ^ Telegraph Reporters (14 August 2012). "Neanderthals did not interbreed with humans, scientists find". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12.

- ^ "Neanderthals 'unlikely to have interbred with human ancestors'". The Guardian. Press Association. 4 February 2013.

- ^ Lowery, Robert K.; Uribe, Gabriel; Jimenez, Eric B.; Weiss, Mark A.; Herrera, Kristian J.; Regueiro, Maria; Herrera, Rene J. (2013). "Neanderthal and Denisova genetic affinities with contemporary humans: Introgression versus common ancestral polymorphisms". Gene. 530 (1): 83–94. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.005. PMID 23872234.

- ^ Israely, Yogev (7 August 2023). "Remains found in China may belong to previously unknown human lineage - Scientists in eastern China examined a jawbone, fragments of a skull and various foot bones from a hominin that lived approximately 300,000 years ago; Findings suggest this particular lineage bears a closer resemblance to Homo sapiens, or modern-day humans". YNet News. Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ Wu, Xiujie; et al. (1 September 2023). "Morphological and morphometric analyses of a late Middle Pleistocene hominin mandible from Hualongdong, China". Journal of Human Evolution. 182. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2023.103411. PMID 37531709. S2CID 260407114. Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search