Back نزيف كانساس Arabic Qanayan Kanzas müharibəsi Azerbaijani Bleeding Kansas Catalan Bleeding Kansas German Bleeding Kansas Spanish Veritsev Kansas Estonian خونریزی کانزاس Persian Bleeding Kansas French קנזס המדממת HE Kansas Berdarah ID

| Bleeding Kansas | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the prelude to the American Civil War | |||||||

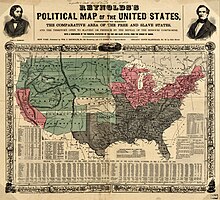

1856 map showing slave states (gray), free states (pink), and territories (green) in the United States, with the Kansas Territory in center (white) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Antislavery settlers Supported by:

|

Pro-slavery settlers (Border ruffians) Supported by:

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John Brown | No centralized leadership | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Disputed – 100+[2] | 80 or fewer; 20–30 killed[2] | ||||||

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the legality of slavery in the proposed state of Kansas.

The conflict was characterized by years of electoral fraud, raids, assaults, and murders carried out in the Kansas Territory and neighboring Missouri by proslavery "border ruffians" and retaliatory raids carried out by antislavery "free-staters". According to Kansapedia of the Kansas Historical Society, 56 political killings were documented during the period,[3] and the total may be as high as 200.[4] It has been called a Tragic Prelude, or an overture, to the American Civil War, which immediately followed it.

The conflict centered on the question of whether Kansas, upon gaining statehood, would join the Union as a slave state or a free state. The question was of national importance because Kansas's two new senators would affect the balance of power in the U.S. Senate, which was bitterly divided over the issue of slavery. The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 called for popular sovereignty: the decision about slavery would be made by popular vote of the territory's settlers rather than by legislators in Washington, D.C. Existing sectional tensions surrounding slavery quickly found focus in Kansas.[5][6]

Missouri, a slave state since 1821, was populated by many settlers with Southern sympathies and proslavery views, some of whom tried to influence the Kansas decision by entering Kansas and claiming to be residents. The conflict was fought politically, and between civilians, where it eventually degenerated into brutal gang violence and paramilitary guerrilla warfare.

Kansas had a state-level civil war that would soon be replicated on a national basis. It had two different capitals (proslavery Lecompton and antislavery Lawrence, then Topeka), two different constitutions (the proslavery Lecompton Constitution and the antislavery Topeka Constitution), and two different legislatures (the so-called "bogus legislature" in Lecompton and the antislavery body in Lawrence). Both sides sought and received help from outside, the proslavery side from the federal government: Presidents Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan openly helped the proslavery partisans.[1] Both claimed to reflect the will of the people of Kansas. The proslavers used violence and threats of violence, and the free-soilers responded in kind. After much commotion, including a congressional investigation, it became clear that a majority of Kansans wanted Kansas to be a free state, but this required congressional approval, which Southerners in Congress blocked.

Kansas was admitted to the Union as a free state the same day that enough Southern senators had departed, during the secession crisis that led to the Civil War, to allow it to pass (effective January 29, 1861). Partisan violence continued along the Kansas–Missouri border for most of the war, although Union control of Kansas was never seriously threatened. Bleeding Kansas demonstrated that armed conflict over slavery was unavoidable. Its severity made national headlines, which suggested to the American people that the sectional disputes were unlikely to be resolved without bloodshed, and it, therefore, acted as a preface to the American Civil War.[7] The episode is commemorated with numerous memorials and historic sites.

- ^ a b c "Bleeding Kansas". History.com. April 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Watts, Dale (1995). "How Bloody Was Bleeding Kansas? Political Killings in Kansas territory, 1854–1861" (PDF). Kansas History. pp. 116–129. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 27, 2012. Retrieved January 9, 2009.

- ^ "Bleeding Kansas". Kansapedia. Kansas Historical Society. 2016. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Finkelman, Paul (Spring 2011). "A Look Back at John Brown". Prologue Magazine. Vol. 43, no. 1. Archived from the original on June 23, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ^ "Bleeding Kansas". American Battlefield Trust. February 14, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "Bleeding Kansas (article)". Khan Academy. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ Etcheson, Nicole. "Bleeding Kansas: From the Kansas–Nebraska Act to Harpers Ferry". Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri–Kansas Conflict, 1854–1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Archived from the original on July 22, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search