Back Brahmi-skrif Afrikaans ब्राह्मी लिपि ANP خط براهمي Arabic ব্ৰাহ্মী লিপি Assamese Brahmi AST Brahmi yazısı Azerbaijani Iskriturang Brahmi BCL Брахми Bulgarian ब्राह्मी लिखाई Bihari ব্রাহ্মী লিপি Bengali/Bangla

| Brahmi Brāhmī | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | At least by the 3rd century BCE[1] to 5th century CE |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit, Tamil, Saka, Tocharian, Telugu, Elu |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Numerous descendant writing systems including:

Devanagari, Kaithi, Sylheti Nagri, Gujarati, Modi, Bengali, Assamese, Sharada, Tirhuta, Odia, Kalinga, Nepalese, Gurmukhi, Khudabadi, Multani, Dogri, Tocharian, Meitei, Lepcha, Tibetan, Bhaiksuki, Siddhaṃ, Takri, ʼPhags-pa

|

Sister systems | Kharosthi |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Brah (300), Brahmi |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Brahmi |

| U+11000–U+1107F | |

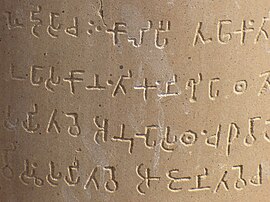

Brahmi (/ˈbrɑːmi/ BRAH-mee; 𑀩𑁆𑀭𑀸𑀳𑁆𑀫𑀻; ISO: Brāhmī) is a writing system of ancient India[2] that appeared as a fully developed script in the 3rd century BCE.[3] Its descendants, the Brahmic scripts, continue to be used today across Southern and Southeastern Asia.[4][5][6]

Brahmi is an abugida which uses a system of diacritical marks to associate vowels with consonant symbols. The writing system only went through relatively minor evolutionary changes from the Mauryan period (3rd century BCE) down to the early Gupta period (4th century CE), and it is thought that as late as the 4th century CE, a literate person could still read and understand Mauryan inscriptions.[7] Sometime thereafter, the ability to read the original Brahmi script was lost. The earliest (indisputably dated) and best-known Brahmi inscriptions are the rock-cut edicts of Ashoka in north-central India, dating to 250–232 BCE.

The decipherment of Brahmi became the focus of European scholarly attention in the early 19th-century during East India Company rule in India, in particular in the Asiatic Society of Bengal in Calcutta.[8][9][10][11] Brahmi was deciphered by James Prinsep, the secretary of the Society, in a series of scholarly articles in the Society's journal in the 1830s.[12][13][14][15] His breakthroughs built on the epigraphic work of Christian Lassen, Edwin Norris, H. H. Wilson and Alexander Cunningham, among others.[16][17][18]

The origin of the script is still much debated, with most scholars stating that Brahmi was derived from or at least influenced by one or more contemporary Semitic scripts. Some non-specialists favour the idea of an indigenous origin or connection to the much older and as yet undeciphered Indus script,[19][20] although this is not generally accepted by epigraphists.[21]

Brahmi was at one time referred to in English as the "pin-man" script,[22] likening the characters to stick figures. It was known by a variety of other names, including "lath", "Laṭ", "Southern Aśokan", "Indian Pali" or "Mauryan" (Salomon 1998, p. 17), until the 1880s when Albert Étienne Jean Baptiste Terrien de Lacouperie, based on an observation by Gabriel Devéria, associated it with the Brahmi script, the first in a list of scripts mentioned in the Lalitavistara Sūtra. Thence the name was adopted in the influential work of Georg Bühler, albeit in the variant form "Brahma".[23]

The Gupta script of the 5th century is sometimes called "Late Brahmi". From the 6th century onward, the Brahmi script diversified into numerous local variants, grouped as the Brahmic family of scripts. Dozens of modern scripts used across South and South East Asia have descended from Brahmi, making it one of the world's most influential writing traditions.[24] One survey found 198 scripts that ultimately derive from it.[25]

Among the inscriptions of Ashoka (c. 3rd century BCE) written in the Brahmi script a few numerals were found, which have come to be called the Brahmi numerals.[26] The numerals are additive and multiplicative and, therefore, not place value;[26] it is not known if their underlying system of numeration has a connection to the Brahmi script.[26] But in the second half of the 1st millennium CE, some inscriptions in India and Southeast Asia written in scripts derived from the Brahmi did include numerals that are decimal place value, and constitute the earliest existing material examples of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, now in use throughout the world.[27] The underlying system of numeration, however, was older, as the earliest attested orally transmitted example dates to the middle of the 3rd century CE in a Sanskrit prose adaptation of a lost Greek work on astrology.[28][29][30]

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 17. "Until the late nineteenth century, the script of the Aśokan (non-Kharosthi) inscriptions and its immediate derivatives was referred to by various names such as 'lath' or 'Lat', 'Southern Aśokan', 'Indian Pali', 'Mauryan', and so on. The application to it of the name Brahmi [sc. lipi], which stands at the head of the Buddhist and Jaina script lists, was first suggested by T[errien] de Lacouperie, who noted that in the Chinese Buddhist encyclopedia Fa yiian chu lin the scripts whose names corresponded to the Brahmi and Kharosthi of the Lalitavistara are described as written from left to right and from right to left, respectively. He therefore suggested that the name Brahmi should refer to the left-to-right 'Indo-Pali' script of the Aśokan pillar inscriptions, and Kharosthi to the right-to-left 'Bactro-Pali' script of the rock inscriptions from the northwest."

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 17. "... the Brahmi script appeared in the third century BCE as a fully developed pan-Indian national script (sometimes used as a second script even within the proper territory of Kharosthi in the north-west) and continued to play this role throughout history, becoming the parent of all of the modern Indic scripts both within India and beyond. Thus, with the exceptions of the Indus script in the protohistoric period, of Kharosthi in the northwest in the ancient period, and of the Perso–Arabic and European scripts in the medieval and modern periods, respectively, the history of writing in India is virtually synonymous with the history of the Brahmi script and its derivatives."

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 19–30.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Salomon 1995was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Brahmi". Encyclopedia Britannica. 1999. Archived from the original on 2020-07-19. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

Among the many descendants of Brāhmī are Devanāgarī (used for Sanskrit, Hindi and other Indian languages), the Bengali and Gujarati scripts and those of the Dravidian languages

- ^ Beckwith, Christopher I. (2017). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-691-17632-1. Archived from the original on 2021-10-14. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- ^ Lahiri, Nayanjot (2015). Ashoka in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. pp. 14, 15. ISBN 978-0-674-05777-7. Archived from the original on 2021-10-18. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

Facsimiles of the objects and writings unearthed—from pillars in North India to rocks in Orissa and Gujarat—found their way to the Asiatic Society of Bengal. The meetings and publications of the Society provided an unusually fertile environment for innovative speculation, with scholars constantly exchanging notes on, for instance, how they had deciphered the Brahmi letters of various epigraphs from Samudragupta's Allahabad pillar inscription, to the Karle cave inscriptions. The Eureka moment came in 1837 when James Prinsep, a brilliant secretary of the Asiatic Society, building on earlier pools of epigraphic knowledge, very quickly uncovered the key to the extinct Mauryan Brahmi script. Prinsep unlocked Ashoka; his deciphering of the script made it possible to read the inscriptions.

- ^ Thapar, Romila (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. pp. 11, 178–179. ISBN 978-0-520-24225-8. Archived from the original on 2021-07-22. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

The nineteenth century saw considerable advances in what came to be called Indology, the study of India by non-Indians using methods of investigation developed by European scholars in the nineteenth century. In India the use of modern techniques to 'rediscover' the past came into practice. Among these was the decipherment of the brahmi script, largely by James Prinsep. Many inscriptions pertaining to the early past were written in brahmi, but knowledge of how to read the script had been lost. Since inscriptions form the annals of Indian history, this decipherment was a major advance that led to the gradual unfolding of the past from sources other than religious and literary texts. [p. 11] ... Until about a hundred years ago in India, Ashoka was merely one of the many kings mentioned in the Mauryan dynastic list included in the Puranas. Elsewhere in the Buddhist tradition he was referred to as a chakravartin, ..., a universal monarch but this tradition had become extinct in India after the decline of Buddhism. However, in 1837, James Prinsep deciphered an inscription written in the earliest Indian script since the Harappan, brahmi. There were many inscriptions in which the King referred to himself as Devanampiya Piyadassi (the beloved of the gods, Piyadassi). The name did not tally with any mentioned in the dynastic lists, although it was mentioned in the Buddhist chronicles of Sri Lanka. Slowly the clues were put together but the final confirmation came in 1915, with the discovery of yet another version of the edicts in which the King calls himself Devanampiya Ashoka. [pp. 178–179]

- ^ Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015). The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BCE – 200 CE. Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-0-521-84697-4. Archived from the original on 2021-11-10. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

Like William Jones, Prinsep was also an important figure within the Asiatic Society and is best known for deciphering early Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts. He was something of a polymath, undertaking research into chemistry, meteorology, Indian scriptures, numismatics, archaeology and mineral resources, while fulfilling the role of Assay Master of the East India Company mint in East Bengal (Kolkata). It was his interest in coins and inscriptions that made him such an important figure in the history of South Asian archaeology, utilising inscribed Indo-Greek coins to decipher Kharosthi and pursuing earlier scholarly work to decipher Brahmi. This work was key to understanding a large part of the Early Historical period in South Asia ...

- ^ Kopf, David (2021). British Orientalism and the Bengal Renaissance: The Dynamics of Indian Modernization 1773–1835. Univ of California Press. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-0-520-36163-8. Archived from the original on 2021-10-14. Retrieved 2021-03-26.

In 1837, four years after Wilson's departure, James Prinsep, then Secretary of the Asiatic Society, unravelled the mystery of the Brahmi script and thus was able to read the edicts of the great Emperor Asoka. The rediscovery of Buddhist India was the last great achievement of the British orientalists. The later discoveries would be made by Continental Orientalists or by Indians themselves.

- ^ Verma, Anjali (2018). Women and Society in Early Medieval India: Re-interpreting Epigraphs. London: Routledge. pp. 27ff. ISBN 978-0-429-82642-9. Archived from the original on 2021-10-14. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

In 1836, James Prinsep published a long series of facsimiles of ancient inscriptions, and this series continued in volumes of the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. The credit for decipherment of the Brahmi script goes to James Prinsep and thereafter Georg Buhler prepared complete and scientific tables of Brahmi and Khrosthi scripts.

- ^ Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2016). A History of India. London: Routledge. pp. 39ff. ISBN 978-1-317-24212-3. Archived from the original on 2021-05-15. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

Ashoka's reign of more than three decades is the first fairly well-documented period of Indian history. Ashoka left us a series of great inscriptions (major rock edicts, minor rock edicts, pillar edicts) which are among the most important records of India's past. Ever since they were discovered and deciphered by the British scholar James Prinsep in the 1830s, several generations of Indologists and historians have studied these inscriptions with great care.

- ^ Wolpert, Stanley A. (2009). A New History of India. Oxford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-19-533756-3. Archived from the original on 2016-05-01. Retrieved 2021-03-26.

James Prinsep, an amateur epigraphist who worked in the British mint in Calcutta, first deciphered the Brāhmi script.

- ^ Chakrabarti, Pratik (2020). Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 48ff. ISBN 978-1-4214-3874-0. Archived from the original on 2021-10-14. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

Prinsep, the Orientalist scholar, as the secretary of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (1832–39), oversaw one of the most productive periods of numismatic and epigraphic study in nineteenth-century India. Between 1833 and 1838, Prinsep published a series of papers based on Indo-Greek coins and his deciphering of Brahmi and Kharoshthi scripts.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 204–205. "Prinsep came to India in 1819 as assistant to the assay master of the Calcutta Mint and remained until 1838, when he returned to England for reasons of health. During this period Prinsep made a long series of discoveries in the fields of epigraphy and numismatics as well as in the natural sciences and technical fields. But he is best known for his breakthroughs in the decipherment of the Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts. ... Although Prinsep's final decipherment was ultimately to rely on paleographic and contextual rather than statistical methods, it is still no less a tribute to his genius that he should have thought to apply such modern techniques to his problem."

- ^ Sircar, D. C. (2017) [1965]. Indian Epigraphy. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 11ff. ISBN 978-81-208-4103-1. Archived from the original on 2021-10-14. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

The work of the reconstruction of the early period of Indian history was inaugurated by European scholars in the 18th century. Later on, Indians also became interested in the subject. The credit for the decipherment of early Indian inscriptions, written in the Brahmi and Kharosthi alphabets, which paved the way for epigraphical and historical studies in India, is due to scholars like Prinsep, Lassen, Norris and Cunningham.

- ^ Garg, Sanjay (2017). "Charles Masson: A footloose antiquarian in Afghanistan and the building up of numismatic collections in museums in India and England". In Himanshu Prabha Ray (ed.). Buddhism and Gandhara: An Archaeology of Museum Collections. Taylor & Francis. pp. 181ff. ISBN 978-1-351-25274-4. Archived from the original on 2020-01-02. Retrieved 2018-09-05.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 20.

- ^ Scharfe, Hartmut (2002). "Kharosti and Brahmi". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 122 (2): 391–393. doi:10.2307/3087634. JSTOR 3087634.

- ^ Damodaram Pillai, Karan (2023). "The hybrid origin of Brahmi script from Aramaic, Phoenician and Greek letters". Indialogs: Spanish Journal of India Studies. 10: 93–122. doi:10.5565/rev/indialogs.213. S2CID 258147647.

- ^ Keay 2000, p. 129–131.

- ^ Falk 1993, p. 106.

- ^ Rajgor 2007.

- ^ Trautmann 2006, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Plofker 2009, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Plofker 2009, p. 45.

- ^ Plofker 2009, p. 47. "A firm upper bound for the date of this invention is attested by a Sanskrit text of the mid-third century CE, the Yavana-jātaka or 'Greek horoscopy' of one Sphujidhvaja, which is a versified form of a translated Greek work on astrology. Some numbers in this text appear in concrete number format."

- ^ Hayashi 2003, p. 119.

- ^ Plofker 2007, pp. 396–397.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search