Back Menseregte Afrikaans Menschenrechte ALS Dreitos humans AN मानवाधिकार ANP حقوق الإنسان Arabic ܙܕܩܐ ܕܒܪܢܫܐ ARC حقوق بنادم ARY حقوق انسان ARZ Derechos humanos AST İnsan hüquqları Azerbaijani

| Rights |

|---|

|

| Theoretical distinctions |

| Human rights |

| Rights by beneficiary |

| Other groups of rights |

Human rights are moral principles, or norms,[1] for certain standards of human behaviour and are regularly protected as substantive rights in substantive law, municipal and international law.[2] They are commonly understood as inalienable,[3] fundamental rights "to which a person is inherently entitled simply because she or he is a human being"[4] and which are "inherent in all human beings",[5] regardless of their age, ethnic origin, location, language, religion, ethnicity, or any other status.[3] They are applicable everywhere and at every time in the sense of being universal,[1] and they are egalitarian in the sense of being the same for everyone.[3] They are regarded as requiring empathy and the rule of law,[6] and imposing an obligation on persons to respect the human rights of others;[1][3] it is generally considered that they should not be taken away except as a result of due process based on specific circumstances.[3]

The doctrine of human rights has been highly influential within international law and global and regional institutions.[3] Actions by states and non-governmental organisations form a basis of public policy worldwide. The idea of human rights suggests that "if the public discourse of peacetime global society can be said to have a common moral language, it is that of human rights".[7] The strong claims made by the doctrine of human rights continue to provoke considerable scepticism and debates about the content, nature and justifications of human rights to this day. The precise meaning of the term right is controversial and is the subject of continued philosophical debate.[8] While there is consensus that human rights encompass a wide variety of rights,[5] such as the right to a fair trial, protection against enslavement, prohibition of genocide, free speech,[9] or a right to education, there is disagreement about which of these particular rights should be included within the general framework of human rights;[1] some thinkers suggest that human rights should be a minimum requirement to avoid the worst-case abuses, while others see it as a higher standard.[1][10] It has also been argued that human rights are "God-given", although this notion has been both criticized[11] and supported.[12]

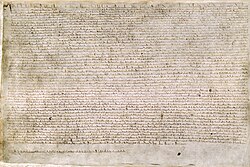

Many of the basic ideas that animated the human rights movement developed in the aftermath of the Second World War and the events of the Holocaust,[6] culminating in the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Paris by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948.[13] Ancient peoples did not have the same modern-day conception of universal human rights.[14] The true forerunner of human rights discourse was the concept of natural rights, which appeared as part of the medieval natural law tradition that became prominent during the European Enlightenment with such philosophers as John Locke, Francis Hutcheson, and Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui, and which featured prominently in the political discourse of the American Revolution and the French Revolution.[6] From this foundation, the modern human rights arguments emerged over the latter half of the 20th century,[15] possibly as a reaction to slavery, torture, genocide, and war crimes,[6] as a realization of inherent human vulnerability and as being a precondition for the possibility of a just society.[5] Human rights advocacy has continued into the early 21st century, centered around achieving greater economic and political freedom.[5]

- ^ a b c d e James Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Human Rights Archived 5 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 14 August 2014

- ^ Nickel (2010).

- ^ a b c d e f The United Nations, Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights, What are human rights? Archived 19 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 14 August 2014

- ^ Sepulveda et al. (2004), p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Burns H. Weston, 20 March 2014, Encyclopædia Britannica, human rights Archived 18 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d Gary J. Bass (book reviewer), Samuel Moyn (author of book being reviewed), 20 October 2010, The New Republic, The Old New Thing Archived 12 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 14 August 2014

- ^ Beitz (2009), p. 1.

- ^ Shaw (2008), p. 265.

- ^ Macmillan Dictionary, human rights – definition Archived 19 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 14 August 2014, "the rights that everyone should have in a society, including the right to express opinions about the government or to have protection from harm"

- ^ International technical guidance on sexuality education: an evidence-informed approach (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. 2018. p. 16. ISBN 978-9231002595. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ Niose, David (6 October 2016). "The Danger of Claiming That Rights Come From God". Psychology Today. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ Vallier, Kevin (28 September 2023). "Human rights and divine holiness". Religious Studies: 1–13. doi:10.1017/S003441252300077X. ISSN 0034-4125.

- ^ Simmons, Beth A. (2009). Mobilizing for Human Rights: International Law in Domestic Politics. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1139483483.

- ^ Freeman (2002), pp. 15–17.

- ^ Moyn (2010), p. 8.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search