Back تنكر Arabic পতংগৰ অনুকাৰিতা আৰু ছদ্মাবৰণ Assamese Мімікрыя Byelorussian Мимикрия Bulgarian Mimetisme Catalan Mimikry Czech Mimicry Danish Mimikry German Kamuflimito Esperanto Mimetismo Spanish

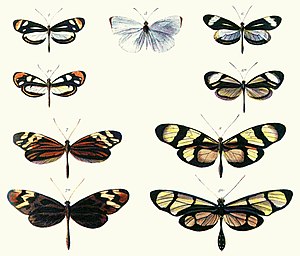

In evolutionary biology, mimicry is an evolved resemblance between an organism and another object, often an organism of another species. Mimicry may evolve between different species, or between individuals of the same species. Often, mimicry functions to protect a species from predators, making it an anti-predator adaptation.[1] Mimicry evolves if a receiver (such as a predator) perceives the similarity between a mimic (the organism that has a resemblance) and a model (the organism it resembles) and as a result changes its behaviour in a way that provides a selective advantage to the mimic.[2] The resemblances that evolve in mimicry can be visual, acoustic, chemical, tactile, or electric, or combinations of these sensory modalities.[2][3] Mimicry may be to the advantage of both organisms that share a resemblance, in which case it is a form of mutualism; or mimicry can be to the detriment of one, making it parasitic or competitive. The evolutionary convergence between groups is driven by the selective action of a signal-receiver or dupe.[4] Birds, for example, use sight to identify palatable insects and butterflies,[5] whilst avoiding the noxious ones. Over time, palatable insects may evolve to resemble noxious ones, making them mimics and the noxious ones models. In the case of mutualism, sometimes both groups are referred to as "co-mimics". It is often thought that models must be more abundant than mimics, but this is not so.[6] Mimicry may involve numerous species; many harmless species such as hoverflies are Batesian mimics of strongly defended species such as wasps, while many such well-defended species form Müllerian mimicry rings, all resembling each other. Mimicry between prey species and their predators often involves three or more species.[7]

In its broadest definition, mimicry can include non-living models. The specific terms masquerade and mimesis are sometimes used when the models are inanimate.[8][3][9] For example, animals such as flower mantises, planthoppers, comma and geometer moth caterpillars resemble twigs, bark, leaves, bird droppings or flowers.[3][6][10][11] Many animals bear eyespots, which are hypothesized to resemble the eyes of larger animals. They may not resemble any specific organism's eyes, and whether or not animals respond to them as eyes is also unclear.[12] Nonetheless, eyespots are the subject of a rich contemporary literature.[13][14][15] The model is usually another species, except in automimicry, where members of the species mimic other members, or other parts of their own bodies, and in inter-sexual mimicry, where members of one sex mimic members of the other.[6]

Mimicry can result in an evolutionary arms race if mimicry negatively affects the model, and the model can evolve a different appearance from the mimic.[6]p161 Mimicry should not be confused with other forms of convergent evolution that occurs when species come to resemble each other by adapting to similar lifestyles that have nothing to do with a common signal receiver. Mimics may have different models for different life cycle stages, or they may be polymorphic, with different individuals imitating different models, such as in Heliconius butterflies. Models themselves may have more than one mimic, though frequency-dependent selection favours mimicry where models outnumber mimics. Models tend to be relatively closely related organisms,[16] but mimicry of vastly different species is also known. Most known mimics are insects,[3] though many other examples including vertebrates are also known. Plants and fungi may also be mimics, though less research has been carried out in this area.[17][18][19][20]

- ^ King, R. C.; Stansfield, W. D.; Mulligan, P. K. (2006). A dictionary of genetics (7th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-19-530762-7.

- ^ a b Dalziell, Anastasia H.; Welbergen, Justin A. (27 April 2016). "Mimicry for all modalities". Ecology Letters. 19 (6): 609–619. Bibcode:2016EcolL..19..609D. doi:10.1111/ele.12602. PMID 27117779.

- ^ a b c d Wickler, Wolfgang (1968). Mimicry in plants and animals. McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Wickler, Wolfgang (1965). "Mimicry and the Evolution of Animal Communication". Nature. 208 (5010): 519–21. Bibcode:1965Natur.208..519W. doi:10.1038/208519a0. S2CID 37649827.

- ^ Radford, Benjamin; Frazier, Kendrick (January 2017). "Cheats and Deceits: How Animals and Plants Exploit and Mislead". Skeptical Inquirer. 41 (1): 60.

- ^ a b c d Ruxton, Graeme D.; Sherratt, T. N.; Speed, M. P. (2004). Avoiding Attack: the Evolutionary Ecology of Crypsis, Warning Signals, and Mimicry. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Kikuchi, D. W.; Pfennig, D. W. (2013). "Imperfect Mimicry and the Limits of Natural Selection". Quarterly Review of Biology. 88 (4): 297–315. doi:10.1086/673758. PMID 24552099. S2CID 11436992.

- ^ Skelhorn, John; Rowland, Hannah M.; Ruxton, Graeme D. (2010). "The Evolution and Ecology of Masquerade". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 99: 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2009.01347.x.

- ^ Pasteur, G. (1982). "A Classificatory Review of Mimicry Systems". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 13: 169–199. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.13.110182.001125.

- ^ Wiklund, Christer; Tullberg, Birgitta S. (September 2004). "Seasonal polyphenism and leaf mimicry in the comma butterfly". Animal Behaviour. 68 (3): 621–627. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.12.008. S2CID 54270418.

- ^ Endler, John A. (August 1981). "An Overview of the Relationships Between Mimicry and Crypsis". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 16 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1981.tb01840.x.

- ^ Stevens, Martin; Hopkins, Elinor; Hinde, William; Adcock, Amabel; Connolly, Yvonne; Troscianko, Tom; Cuthill, Innes C. (November 2007). "Field Experiments on the effectiveness of 'eyespots' as predator deterrents". Animal Behaviour. 74 (5): 1215–1227. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.01.031. S2CID 53186893.

- ^ Stevens, Martin (22 June 2007). "Predator perception and the interrelation between different forms of protective coloration". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 274 (1617): 1457–1464. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0220. PMC 1950298. PMID 17426012.

- ^ Stevens, Martin; Stubbins, Claire L.; Hardman, Chloe J. (30 May 2008). "The anti-predator function of 'eyespots' on camouflaged and conspicuous prey". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 62 (11): 1787–1793. doi:10.1007/s00265-008-0607-3. S2CID 28288920.

- ^ Hossie, Thomas John; Sherratt, Thomas N. (August 2013). "Defensive posture and eyespots deter avian predators from attacking caterpillar models". Animal Behaviour. 86 (2): 383–389. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.05.029. S2CID 53263767.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Campbellwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Boyden, T. C. (1980). "Floral mimicry by Epidendrum ibaguense (Orchidaceae) in Panama". Evolution. 34 (1): 135–136. doi:10.2307/2408322. JSTOR 2408322. PMID 28563205.

- ^ Roy, B. A. (1994). "The effects of pathogen-induced pseudoflowers and buttercups on each other's insect visitation". Ecology. 75 (2): 352–358. Bibcode:1994Ecol...75..352R. doi:10.2307/1939539. JSTOR 1939539.

- ^ Wickler, Wolfgang, 1998. "Mimicry". Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th edition. Macropædia 24, 144–151. https://www.britannica.com/eb/article-11910

- ^ Johnson, Steven D.; Schiestl, Florian P. (2016). Floral Mimicry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-104723-7.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search