Back New York City draft riots Breton New York Draft Riots Danish Draft Riots German Draft Riots Spanish New Yorkin kutsuntamellakka Finnish Draft Riots French Círéibeacha coinscríobh Cathair Nua-Eabhrac Irish מהומות הגיוס בניו יורק HE New York-i felkelés Hungarian Kerusuhan Draf Kota New York ID

| New York City Draft Riots of 1863 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Opposition to the American Civil War | |||

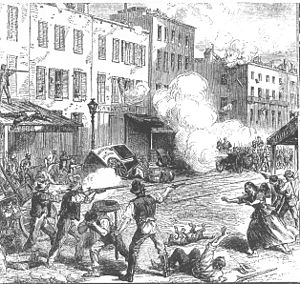

An illustration in The Illustrated London News depicting armed rioters clashing with Union Army soldiers in New York City | |||

| Date | July 13–16, 1863 | ||

| Location | Manhattan, New York City, U.S. | ||

| Caused by | Civil War conscription; racism; competition for jobs between blacks and whites. | ||

| Resulted in | Riots ultimately suppressed | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 119–120[1][2] | ||

| Injuries | 2,000 | ||

The New York City draft riots (July 13–16, 1863), sometimes referred to as the Manhattan draft riots and known at the time as Draft Week,[3] were violent disturbances in Lower Manhattan, widely regarded as the culmination of working-class discontent with new laws passed by Congress that year to draft men to fight in the ongoing American Civil War. The riots remain the largest civil and most racially charged urban disturbance in American history.[4] According to Toby Joyce, the riot represented a "civil war" within the city's Irish community, in that "mostly Irish American rioters confronted police, [while] soldiers, and pro-war politicians ... were also to a considerable extent from the local Irish immigrant community."[5]

President Abraham Lincoln diverted several regiments of militia and volunteer troops after the Battle of Gettysburg to control the city. The rioters were overwhelmingly Irish working-class men who did not want to fight in the Civil War and resented that wealthier men, who could afford to pay a $300 commutation fee to hire a substitute, were spared from the draft.[6][7] At the time a typical laborer's wage was between $1.00 and $2.00 a day, and the fee was equivalent to $7,400 in 2023.[8][9][10]

Initially intended to express anger at the draft, the protests turned into a race riot against African-Americans by Irish rioters. The Irish resented the fact that free blacks were paid more than them and did not need to fear being drafted, whereas the Irish could only avoid the draft by paying $300. The official death toll was listed at either 119 or 120 individuals. Conditions in the city were such that Major General John E. Wool, commander of the Department of the East, said on July 16 that "Martial law ought to be proclaimed, but I have not a sufficient force to enforce it."[11]

The military did not reach the city until the second day of rioting, by which time the mobs had ransacked or destroyed numerous public buildings, two Protestant churches, the homes of various abolitionists or sympathizers, many black homes, and the Colored Orphan Asylum at 44th Street and Fifth Avenue, which was burned to the ground.[12] The area's demographics changed as a result of the riot. Many black residents left Manhattan permanently with many moving to Brooklyn. By 1865, the black population had fallen below 11,000 for the first time since 1820.[12]

- ^ McPherson, James M. (1982), Ordeal By Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, p. 360, ISBN 978-0-394-52469-6

- ^ "VNY: Draft Riots Aftermath". Vny.cuny.edu. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ Barnes, David M. (1863). The Draft Riots in New York, July 1863: The Metropolitan Police, Their Services During Riot. Baker & Godwin. pp. 5–6, 12.

- ^ Foner, Eric (1988). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. The New American Nation. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 32–33. ISBN 0-06-093716-5. (updated ed. 2014, ISBN 978-0062354518).

- ^ Toby Joyce, "The New York Draft Riots of 1863: An Irish Civil War?" History Ireland (March 2003) 11#2, pp 22–27.

- ^ "Prologue: Selected Articles". Archives.org. August 15, 1990. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ "The Draft in the Civil War". United States History. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "The journal of political economy. v.13 1905". HathiTrust. 1892. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Statistics, United States Bureau of Labor; Stewart, Estelle M. (Estelle May); Bowen, Jesse Chester (October 1, 1929). "History of Wages in the United States From Colonial Times to 1928 : Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, No. 499".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Maj. Gen. John E. Wool Official Reports for the New York Draft Riots". Shotgun's Home of the American Civil War blogsite. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ a b Harris, Leslie M. (2003). In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626–1863. University of Chicago Press. pp. 279–88. ISBN 0226317757.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search