Back حروب البرتغال الاستعمارية Arabic Guerra colonial portuguesa AST سومورگه پورتاغال ساواشی AZB Guerra colonial portuguesa Catalan Portugalská koloniální válka Czech Portugiesischer Kolonialkrieg German Guerra colonial portuguesa Spanish Portugali koloniaalsõda Estonian جنگ استعماری پرتغال Persian Portugalin siirtomaasodat Finnish

| Portuguese Colonial War Guerra Colonial Portuguesa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War and decolonisation of Africa | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Supported by:

|

Angola:

Guinea:

Mozambique:

Supported by:

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Angola: Guinea: Mozambique: | Angola: Guinea: Mozambique: | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

1,400,000 total men mobilized for military and civilian support service.[23]

|

40,000–60,000 guerrillas[25]

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

29,000 casualties

|

26,000+ casualties | ||||||||

| Civilian casualties: ~110,000 dead Over 300,000 Portuguese nationals evacuated. | |||||||||

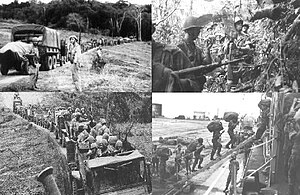

The Portuguese Colonial War (Portuguese: Guerra Colonial Portuguesa), also known in Portugal as the Overseas War (Guerra do Ultramar) or in the former colonies as the War of Liberation (Guerra de Libertação), and also known as the Angolan, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambican War of Independence, was a 13-year-long conflict fought between Portugal's military and the emerging nationalist movements in Portugal's African colonies between 1961 and 1974. The Portuguese regime at the time, the Estado Novo, was overthrown by a military coup in 1974, and the change in government brought the conflict to an end. The war was a decisive ideological struggle in Lusophone Africa, surrounding nations, and mainland Portugal.

The prevalent Portuguese and international historical approach considers the Portuguese Colonial War as was perceived at the time—a single conflict fought in the three separate Angolan, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambican theaters of operations, rather than a number of separate conflicts as the emergent African countries aided each other and were supported by the same global powers and even the United Nations during the war. India's 1954 annexation of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and 1961 annexation of Goa are sometimes included as part of the conflict.

Unlike other European nations during the 1950s and 1960s, the Portuguese Estado Novo regime did not withdraw from its African colonies, or the overseas provinces (províncias ultramarinas) as those territories had been officially called since 1951. During the 1960s, various armed independence movements became active—the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola, National Liberation Front of Angola, National Union for the Total Independence of Angola in Angola, African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde in Portuguese Guinea, and the Mozambique Liberation Front in Mozambique. During the ensuing conflict, atrocities were committed by all forces involved.[38]

Throughout the period, Portugal faced increasing dissent, arms embargoes, and other punitive sanctions imposed by the international community, including by some Western Bloc governments, either intermittently or continuously.[39] The anti-colonial guerrillas and movements of Portuguese Africa were heavily supported and instigated with money, weapons, training and diplomatic lobbying by the Communist Bloc which had the Soviet Union as its lead nation. By 1973, the war had become increasingly unpopular due to its length and financial costs, the worsening of diplomatic relations with other United Nations members, and the role it had always played as a factor of perpetuation of the entrenched Estado Novo regime and the nondemocratic status quo in Portugal.

The end of the war came with the Carnation Revolution military coup of April 1974 in mainland Portugal. The withdrawal resulted in the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Portuguese citizens[40] plus military personnel of European, African, and mixed ethnicity from the former Portuguese territories and newly independent African nations.[41][42][43] This migration is regarded as one of the largest peaceful, if forced, migrations in the world's history although most of the migrants fled the former Portuguese territories as destitute refugees.[44]

The former colonies faced severe problems after independence. Devastating civil wars followed in Angola and Mozambique, which lasted several decades, claimed millions of lives, and resulted in large numbers of displaced refugees.[45] Angola and Mozambique established state-planned economies after independence,[46] and struggled with inefficient judicial systems and bureaucracies,[46] corruption,[46][47][48] poverty and unemployment.[47] A level of social order and economic development comparable to what had existed under Portuguese rule, including during the period of the Colonial War, became the goal of the independent territories.[49]

The former Portuguese territories in Africa became sovereign states, with Agostinho Neto in Angola, Samora Machel in Mozambique, Luís Cabral in Guinea-Bissau, Manuel Pinto da Costa in São Tomé and Príncipe, and Aristides Pereira in Cape Verde as the heads of state.

- ^ Telepneva, Natalia (2022). Cold War Liberation: The Soviet Union and the Collapse of the Portuguese Empire in Africa, 1961-1975. The University of North Carolina Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-4696-6586-3.

- ^ Telepneva, Natalia (2022). Cold War Liberation: The Soviet Union and the Collapse of the Portuguese Empire in Africa, 1961-1975. The University of North Carolina Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-4696-6586-3.

- ^ Robert J. Griffiths:U.S. Security Cooperation with Africa: Political and Policy Challenges, Routledge, 2016, p.75.

- ^ Ronald Dreyer:Namibia & Southern Africa, Routledge, 2016, p. 89.

- ^ Cox, Courtland (1976) "The U.S. Involvement in Angola", New Directions: Vol. 3: Iss. 2, Article 4. Available at: https://dh.howard.edu/newdirections/vol3/iss2/4

- ^ Mike Bowker, Phil Williams: Superpower Detente, SAGE, 1988, p. 117. "The CIA had supplied Roberto with money and arms from 1962 to 1969."

- ^ a b c d e Miguel Cardina: The Portuguese Colonial War and the African Liberation Struggles: Memory, Politics and Uses of the Past, Taylor & Francis, 2023, p. 166. "Besides cooperation from Guinea-Conakry and Senegal, the movement [PAIGC] also received military and technical assistance, primarily from the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, China and Cuba.

- ^ Tor Sellström:Sweden and National Liberation in Southern Africa: Solidarity and assistance, 1970-1994, Nordic Africa Institute, 1999, p. 50.

- ^ Lena Dallywater, Chris Saunders, Helder Adegar Fonseca: Southern African Liberation Movements and the Global Cold War ‘East’: Transnational Activism 1960–1990, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, Jun 17, 2019. "Yugoslavia donated military equipment, money, and provided training and medical services to the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO), the PAIGC, and the MPLA."

- ^ Philip E. Muehlenbeck, Natalia Telepneva: Warsaw Pact Intervention in the Third World: Aid and Influence in the Cold War, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018, pp. 313-314.

- ^ Emizet Francois Kisangani, Scott F. Bobb: Historical Dictionary of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Scarecrow Press, 2009, p. 458.

- ^ Figueiredo, António de (1961). Portugal and Its Empire: The Truth. p. 130.

- ^ Roy Pateman: Residual Uncertainty: Trying to Avoid Intelligence and Policy Mistakes in the Modern World, University Press of America, 2003, p. 110.

- ^ Jane Haapiseva-Hunter: Israeli Foreign Policy: South Africa and Central America, South End Press, 1987, p. 59.

- ^ Paraska Tolan-Szkilnik: Maghreb Noir: The Militant-Artists of North Africa and the Struggle for a Pan-African, Postcolonial Future, Stanford University Press, 2023.

- ^ Selcher, Wayne A. (1976). "Brazilian Relations with Portuguese Africa in the Context of the Elusive "Luso-Brazilian Community"". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 18 (1): 25–58. doi:10.2307/174815. JSTOR 174815.

- ^ Falola, Toyin; Oyebade, Adebayo O. (2010-07-01). Hot Spot: Sub-Saharan Africa. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-0-313-35972-9.

- ^ Kennes, Erik; Larmer, Miles (2016-07-04). The Katangese Gendarmes and War in Central Africa. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-02150-2.

- ^ Cann, John (2014-01-19). The Flechas: Insurgent Hunting in Eastern Angola, 1965–1974. Helion and Company. ISBN 978-1-909384-63-7.

- ^ The New Encyclopaedia Britannica: Macropaedia : Knowledge in depth. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2003. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- ^ Falola, Toyin; Oyebade, Adebayo O. (2010-07-01). Hot Spot: Sub-Saharan Africa. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-0-313-35972-9.

- ^ Mia Couto, Carnation revolution, Le Monde Diplomatique

- ^ a b Fátima da Cruz Rodrigues: A desmobilização dos combatentes africanos das Forças Armadas Portuguesas da Guerra Colonial (1961-1974), 2013.

- ^ "Os anos da guerra 1961-1975, Os portugueses em África, crónica, ficção e história" (1988) by João de Melo, p.396

- ^ "Portugal Angola War 1961–1975". Onwar.com. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ "Angola Army - History".

- ^ Campos, Ângela (November 20, 2008). ""We are still ashamed of our own History". Interviewing ex-combatants of the portuguese colonial war (1961-1974)". Lusotopie. Recherches politiques internationales sur les espaces issus de l'histoire et de la colonisation portugaises (XV(2)): 107–126. doi:10.1163/17683084-01502006 – via journals.openedition.org.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lloyd-Jones, Stewart p. 22was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ PAIGC, Jornal Nô Pintcha, 29 November 1980: In a statement in the party newspaper Nô Pintcha (In the Vanguard), a spokesman for the PAIGC revealed that many of the ex-Portuguese indigenous African soldiers that were executed after cessation of hostilities were buried in unmarked collective graves in the woods of Cumerá, Portogole, and Mansabá.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Munslow, Barry 1981 pp. 109-113was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Aniceto Afonso, Carlos de Matos Gomes: Guerra Colonial. Lisbon 2000, p. 528.

- ^ "Portugal Angola War 1961–1975". Onwar.com. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Twentieth Century Atlas - Death Tolls". users.erols.com.

- ^ "Twentieth Century Atlas - Death Tolls". users.erols.com.

- ^ Mid-Range Wars and Atrocities of the Twentieth Century retrieved December 4, 2007

- ^ Tom Hartman, A World Atlas of Military History 1945–1984.

- ^ Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015 (4th ed.). McFarland. p. 561. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- ^ "Portugal: Kolonien auf Zeit?". Der Spiegel (in German). August 13, 1973.

- ^ Consideration of Questions Under The Council's Responsibility For The Maintenance of International Peace and Security (PDF). Vol. 8. United Nations. pp. 113, 170–72.

- ^ Portugal Migration, The Encyclopedia of the Nations

- ^ Flight from Angola, The Economist (August 16, 1975).

- ^ Dismantling the Portuguese Empire, Time magazine (July 7, 1975).

- ^ Portugal – Emigration, Eric Solsten, ed, 1993. Portugal: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress.

- ^ António Barreto, 2006, Portugal: Um Retrato Social

- ^ Stuart A. Notholt (Apr., 1998) Review: ‘The Decolonization of Portuguese Africa: Metropolitan Revolution and the Dissolution of Empire by Norrie MacQueen – Mozambique since Independence: Confronting Leviathan by Margaret Hall, Tom Young’ African Affairs, Vol. 97, No. 387, pp. 276–78, JSTOR 723274

- ^ a b c Susan Rose-Ackerman, 2009, "Corruption in the Wake of Domestic National Conflict" in Corruption, Global Security, and World Order (ed. Robert I. Rotberg: Brookings Institution), p. 79.

- ^ a b Mario de Queiroz, Africa–Portugal: Three Decades After Last Colonial Empire Came to an End, Inter Press Service (November 23, 2005).

- ^ Tim Butcher, As guerrilla war ends, corruption now bleeds Angola to death, The Daily Telegraph (30 July 2002)

- ^ "Things are going well in Angola. They achieved good progress in their first year of independence. There's been a lot of building and they are developing health facilities. In 1976, they produced 80,000 tons of coffee. Transportation means are also being developed. Currently, between 200,000 and 400,000 tons of coffee are still in warehouses. In our talks with [Angolan President Agostinho] Neto we stressed the absolute necessity of achieving a level of economic development comparable to what had existed under [Portuguese] colonialism."; "There is also evidence of black racism in Angola. Some are using the hatred against the colonial masters for negative purposes. There are many mulattos and whites in Angola. Unfortunately, racist feelings are spreading very quickly." Castro's 1977 southern Africa tour: A report to Honecker, CNN

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search