Back Statue National Museum Karatschi 50.852 German Pastro-Reĝo (skulptaĵo) Esperanto Roi-Prêtre de Mohenjo-daro French 神官王像 Japanese Цар-жрець (скульптура) Ukrainian

| Priest-King | |

|---|---|

The Priest King | |

| Artist | unknown, prehistoric |

| Year | c. 2000–1900 BCE |

| Type | fired steatite |

| Dimensions | 17.5 cm × 11 cm (6.9 in × 4.3 in ) |

| Location | National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi |

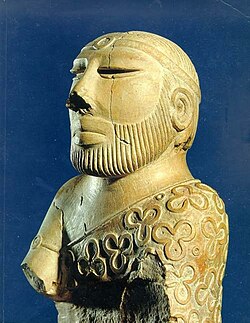

The Priest-King, in Pakistan often King-Priest,[1] is a small male figure sculpted in steatite found during the excavation of the ruined Bronze Age city of Mohenjo-daro in Sindh, Pakistan, in 1925–26. It is dated to around 2000–1900 BCE, in Mohenjo-daro's Late Period, and is "the most famous stone sculpture" of the Indus Valley civilization ("IVC").[2] It is now in the collection of the National Museum of Pakistan as NMP 50-852. It is widely admired, as "the sculptor combined naturalistic detail with stylized forms to create a powerful image that appears much bigger than it actually is,"[3] and excepting possibly the Pashupati Seal, "nothing has come to symbolize the Indus Civilization better."[4]

The sculpture shows a neatly bearded man with a fillet around his head, possibly all that is left of a once-elaborate hairstyle or headdress; his hair is combed back. He wears an armband, and a cloak with drilled trefoil, single circle and double circle motifs, which show traces of red. His eyes might have originally been inlaid.[5] The sculpture is incomplete, broken off at the bottom, and possibly unfinished. Originally it was presumably larger and probably was a full-length seated or kneeling figure.[6] As it is now, it is 17.5 centimetres (6.9 in) high.[7]

Though the name Priest-King is now generally used, it is highly speculative, and "without foundation".[8] Ernest J. H. Mackay, the archaeologist leading the excavations at the site when the piece was found, thought it might represent a "priest". Sir John Marshall, head of the pre-Partition Archaeological Survey of India ("ASI") at the time, regarded it as possibly a "king-priest", but it appears to have been his successor, Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who was the first to use Priest-King.[9] An alternative designation for this and a few other IVC male figure sculptures is that they "are commemorative figures of clan leaders or ancestral figures".[3]

A replica is normally displayed at the National Museum of Pakistan, while the original is kept secure. Mr. Bukhari, the director of the museum explained in 2015 "It's a national symbol. We can't take risks with it".[10] The Urdu language title used by the museum (with the English "King-Priest") is not an exact translation, but حاکم اعلی (hakim aala), a well-known expression in Urdu-Persian-Arabic meaning a sovereign or bishop (who is entitled to sit in a chair of state on ceremonial occasions).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search