Back ديانة شعبية صينية Arabic ديانه شعبيه صينيه ARZ Relixón tradicional china AST Ҡытай халыҡ дине Bashkir চীনা লোকজ ধর্ম Bengali/Bangla Religió tradicional xinesa Catalan Čínské lidové náboženství Czech Chinesischer Volksglaube German Tradicia ĉina religio Esperanto Religión tradicional china Spanish

| Chinese folk religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

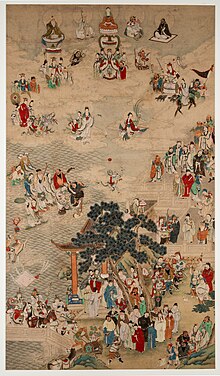

Qing dynasty painting of the Chinese pantheon. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國民間信仰 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国民间信仰 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese folk religion |

|---|

|

Chinese folk religion, also known as Chinese popular religion, comprehends a range of traditional religious practices of Han Chinese, including the Chinese diaspora. Vivienne Wee described it as "an empty bowl, which can variously be filled with the contents of institutionalised religions such as Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism and Chinese syncretic religions".[1] This includes the veneration of shen (spirits) and ancestors.[2] Worship is devoted to deities and immortals, who can be deities of places or natural phenomena, of human behaviour, or founders of family lineages. Stories of these gods are collected into the body of Chinese mythology. By the Song dynasty (960–1279), these practices had been blended with Buddhist, Confucian, and Taoist teachings to form the popular religious system which has lasted in many ways until the present day.[3] The present day government of mainland China, like the imperial dynasties, tolerates popular religious organizations if they bolster social stability but suppresses or persecutes those that they fear would undermine it.[4]

After the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911, governments and modernizing elites condemned "feudal superstition" and opposed or attempted to eradicate traditional religious practices which they believed conflicted with modern values. By the late 20th century, these attitudes began to change both in Taiwan and in mainland China, and many scholars now view folk religion in a positive light.[5] In recent times traditional religion is experiencing a revival in both China and Taiwan. Some forms have received official understanding or recognition as a preservation of traditional culture, such as Mazuism and the Sanyi teaching in Fujian,[6] Huangdi worship,[7] and other forms of local worship, for example the Longwang, Pangu or Caishen worship.[8]

Geomancy, acupuncture, and traditional Chinese medicine reflect this world view, since features of the landscape as well as organs of the body are in correlation with the five powers and yin and yang.[9]

- ^ Wee, Vivienne (1976). "'Buddhism' in Singapore". In Hassan, Riaz (ed.). In Singapore: Society in Transition. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. pp. 155–188. The restriction of Christianity to Catholicism in her definition has since been broadened by the findings of other investigators.

- ^ Teiser (1995), p. 378.

- ^ Overmyer (1986), p. 51.

- ^ Madsen, Richard (October 2010). "The Upsurge of Religion in China" (PDF). Journal of Democracy. 21 (4). Johns Hopkins University Press for the National Endowment for Democracy: 64–65. doi:10.1353/jod.2010.0013. S2CID 145160849. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ Gaenssbauer (2015), p. 28-37.

- ^ Zhuo, Xinping (2014). "Civil Society and the Multiple Existence of Religions". Relationship between Religion and State in the People's Republic of China - Religions & Christianity in Today's China (PDF). Vol. 4. pp. 22–23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 May 2014.

- ^ Sautman, 1997. pp. 80–81

- ^ Adam Yuet Chau. "The Policy of Legitimation and the Revival of Popular Religion in Shaanbei, North-Central China Archived 28 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine". Modern China. SAGE Publications. 31.2, 2005. pp. 236–278

- ^ Overmyer (1986), p. 86.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search