Back جمعية الأصدقاء الدينية Arabic الكويكرز ARZ Sociedá Relixosa de los Amigos AST Квакеры Byelorussian Квакеры BE-X-OLD Квакери Bulgarian Kevredigezh relijius ar Vignoned Breton Kvekeri BS Societat Religiosa d'Amics Catalan Kvakeři Czech

| Religious Society of Friends | |

|---|---|

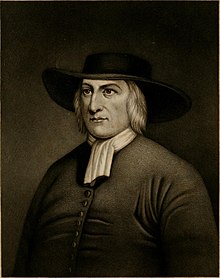

George Fox, the principal early leader of the Quakers | |

| Theology | Variable; depends on meeting |

| Polity | Congregational |

| Distinct fellowships | Friends World Committee for Consultation |

| Associations | Britain Yearly Meeting, Friends United Meeting, Evangelical Friends Church International, Central Yearly Meeting of Friends, Conservative Friends, Friends General Conference, Beanite Quakerism |

| Founder | George Fox Margaret Fell |

| Origin | Mid-17th century England |

| Separated from | Church of England |

| Separations | Shakers[1] |

| Part of a series on |

| Quakerism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Protestantism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members of these movements ("the Friends") are generally united by a belief in each human's ability to be guided by the inward light, "answering that of God in every one".[2][3] Friends have traditionally professed a priesthood of all believers inspired by the First Epistle of Peter.[4][5][6][7] They include those with evangelical, holiness, liberal, and traditional Quaker understandings of Christianity, as well as Nontheist Quakers. To differing extents, the Friends avoid creeds and hierarchical structures.[8] In 2017, there were an estimated 377,557 adult Quakers, 49% of them in Africa.[9]

Some 89% of Quakers worldwide belong to evangelical and programmed branches (the largest Quaker group being the Evangelical Friends Church International)[10][11] that hold services with singing and a prepared Bible message coordinated by a pastor. Some 11% practice waiting worship or unprogrammed worship (commonly Meeting for Worship),[12] where the unplanned order of service is mainly silent and may include unprepared vocal ministry from those present. Some meetings of both types have Recorded Ministers present, Friends recognised for their gift of vocal ministry.[13]

The proto-evangelical Christian movement dubbed Quakerism arose in mid-17th-century England from the Legatine-Arians and other dissenting Protestant groups breaking with the established Church of England.[14] The Quakers, especially the Valiant Sixty, sought to convert others by travelling through Britain and overseas preaching the Gospel. Some early Quaker ministers were women.[15] They based their message on a belief that "Christ has come to teach his people himself", stressing direct relations with God through Jesus Christ and belief in the universal priesthood of all believers.[16] This personal religious experience of Christ was acquired by direct experience and by reading and studying the Bible.[17] Quakers focused their private lives on behaviour and speech reflecting emotional purity and the light of God, with a goal of Christian perfection.[18][19] A prominent theological text of the Religious Society of Friends is A Catechism and Confession of Faith (1673), published by Quaker divine Robert Barclay.[20][21] The Richmond Declaration of Faith (1887) was adopted by many Orthodox Friends and continues to serve as a doctrinal statement of many yearly meetings.[22][23]

Quakers were known to use thee as an ordinary pronoun, refuse to participate in war, wear plain dress, refuse to swear oaths, oppose slavery, and practice teetotalism.[24] Some Quakers founded banks and financial institutions, including Barclays, Lloyds, and Friends Provident; manufacturers including the footwear firm of C. & J. Clark and the big three British confectionery makers Cadbury, Rowntree and Fry; and philanthropic efforts, including abolition of slavery, prison reform, and social justice.[25] In 1947, in recognition of their dedication to peace and the common good, Quakers represented by the British Friends Service Council and the American Friends Service Committee were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[26][27]

- ^ Michael Bjerknes Aune; Valerie M. DeMarinis (1996). Religious and Social Ritual: Interdisciplinary Explorations. SUNY Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-7914-2825-2.

- ^ Fox, George (1903). George Fox's Journal. Isbister and Company Limited. pp. 215–216.

This is the word of the Lord God to you all, and a charge to you all in the presence of the living God; be patterns, be examples in all your countries, places, islands, nations, wherever you come; that your carriage and life may preach among all sorts of people and to them: then you will come to walk cheerfully over the world, answering that of God in every one; whereby in them ye may be a blessing, and make the witness of God in them to bless you: then to the Lord God you will be a sweet savour, and a blessing.

- ^ Hodge, Charles (12 March 2015). Systematic Theology. Delmarva Publications, Inc. p. 137.

This spiritual illumination is peculiar to the true people of God; the inward lihgt, in which the Quakers believe, is common to all men. The design and effect of the "inward light" are the communication of new truth, or of truth not objectively revealed, as well as the spiritual discernment of the truths of Scripture. The design and effect of spiritual illumination are the proper apprehension of truth already speculatively known. Secondly. By the inner light the orthodox Quakers understand the supernatural influence of the Holy Spirit, concerning which they teach, – (1.) That it is given to all men. (2.) That it not only convinces of sin, and enables the soul to apprehend aright the truths of Scripture, but also communicates a knowledge of "the mysteries of salvation." ... The orthodox Friends teach concerning this inward light, as has been already shown, that it is subordinate to the Holy Scriptures, inasmuch as the Scriptures are the infallible rule of faith and practice, and everything contrary thereto is to be rejected as false and destructive.

- ^ "Membership | Quaker faith & practice". qfp.quaker.org.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ "Baltimore Yearly Meeting Faith & Practice". August 2011. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012.

- ^ 1 Peter 2:9

- ^ "'That of God' in every person". Quakers in Belgium and Luxembourg.

- ^ Fager, Chuck. "The Trouble With 'Ministers'". quakertheology.org. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ "Finding Quakers Around the World" (PDF). Friends World Committee for Consultation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain (2012). Epistles and Testimonies (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2016.

- ^ Angell, Stephen Ward; Dandelion, Pink (19 April 2018). The Cambridge Companion to Quakerism. Cambridge University Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-1-107-13660-1.

Contemporary Quakers worldwide are predominately evangelical and are often referred to as the Friends Church.

- ^ Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain (2012). Epistles and Testimonies (PDF). p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2015. [dead link]

- ^ Drayton, Brian (23 December 1994). "FGC Library: Recorded Ministers in the Society of Friends, Then and Now". Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Christian Scholar's Review, Volume 27. Hope College. 1997. p. 205.

This was especially true of proto-evangelical movements like the Quakers, organized as the Religious Society of Friends by George Fox in 1668 as a group of Christians who rejected clerical authority and taught that the Holy Spirit guided

- ^ Bacon, Margaret (1986). Mothers of Feminism: The Story of Quaker Women in America. San Francisco: Harper & Row. p. 24.

- ^ Fox, George (1803). Armistead, Wilson (ed.). Journal of George Fox. Vol. 2 (7 ed.). p. 186.

- ^ World Council of Churches. "Friends (Quakers)". Church Families. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011.

- ^ Stewart, Kathleen Anne (1992). The York Retreat in the Light of the Quaker Way: Moral Treatment Theory : Humane Therapy Or Mind Control?. William Sessions. ISBN 9781850720898.

On the other hand, Fox believed that perfectionism and freedom from sin were possible in this world.

- ^ Levy, Barry (30 June 1988). Quakers and the American Family: British Settlement in the Delaware Valley. Oxford University Press, US. pp. 128. ISBN 9780198021674.

- ^ Coffey, John (29 May 2020). The Oxford History of Protestant Dissenting Traditions, Volume I: The Post-Reformation Era, 1559-1689. Oxford University Press. p. 399. ISBN 978-0-19-252098-2.

- ^ A Short Account of the Life and Writings of Robert Barclay. Tract Association of the Society of Friends. 1827. p. 22.

- ^ Williams, Walter R. (13 January 2019). The Rich Heritage of Quakerism. Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78912-341-8.

From time to time, over the three centuries of their history, Friends have issued longer or shorter statements of belief. They earnestly seek to base these declarations of the essential truths of Christianity upon the clear teaching of the Holy Scriptures. The most detailed of these statements commonly held by orthodox Friends is known as the Richmond Declaration of Faith. This instrument was drawn up by ninety-nine representatives of ten American yearly meetings and of London and Dublin yearly meetings, assembled at Richmond, Indiana, in 1887.

- ^ "Declaration of Faith Issued by the Richmond Conference in 1887". 23 July 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

Declaration of Faith Issued by the Richmond Conference in 1887

- ^ "Society of Friends | religion". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ Jackson, Peter (20 January 2010). "How did Quakers conquer the British sweet shop?". BBC News. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Jahn, Gunnar. "Award Ceremony Speech (1947)". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ Abrams, Irwin (1991). "The Quaker Peace Testimony and the Nobel Peace Prize". Retrieved 24 November 2018.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search