Back معركة أنتيتام Arabic Batalla d'Antietam AST Eynthem müharibəsi Azerbaijani اینتهم ساواشی AZB Битка при Антиетам Bulgarian Emgann Antietam Breton Batalla d'Antietam Catalan Slaget ved Antietam Danish Schlacht am Antietam German Batalo de Antietam Esperanto

| Battle of Antietam Battle of Sharpsburg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

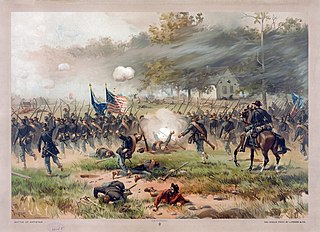

Depiction of the fighting near Dunker Church by Thure de Thulstrup | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 275 artillery |

30,646 engaged[8] 194 artillery | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

12,410 2,108 killed 9,549 wounded 753 captured/missing[9][10] |

10,337 1,567 killed 7,752 wounded 1,018 captured/missing[10] | ||||||

The Battle of Antietam (/ænˈtiːtəm/ an-TEE-təm), also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union Major General George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek. Part of the Maryland Campaign, it was the first field army–level engagement in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War to take place on Union soil. It remains the bloodiest day in American history, with a tally of 22,727 dead, wounded, or missing on both sides. Although the Union Army suffered heavier casualties than the Confederates, the battle was a major turning point in the Union's favor.

After pursuing Confederate General Robert E. Lee into Maryland, Major General George B. McClellan of the Union Army launched attacks against Lee's army who were in defensive positions behind Antietam Creek. At dawn on September 17, Major General Joseph Hooker's corps mounted a powerful assault on Lee's left flank. Attacks and counterattacks swept across Miller's Cornfield, and fighting swirled around the Dunker Church. Union assaults against the Sunken Road eventually pierced the Confederate center, but the Federal advantage was not followed up. In the afternoon, Union Major General Ambrose Burnside's corps entered the action, capturing a stone bridge over Antietam Creek and advancing against the Confederate right. At a crucial moment, Confederate Major General A. P. Hill's division arrived from Harpers Ferry and launched a surprise counterattack, driving back Burnside and ending the battle. Although outnumbered two-to-one, Lee committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in less than three-quarters of his army, enabling Lee to fight the Federals to a standstill. During the night, both armies consolidated their lines. In spite of crippling casualties, Lee continued to skirmish with McClellan throughout September 18, while removing his battered army south of the Potomac River.

McClellan successfully turned Lee's invasion back, making the battle a strategic Union victory. From a tactical standpoint, the battle was somewhat inconclusive; the Union Army successfully repelled the Confederate invasion but suffered heavier casualties and failed to defeat Lee's army outright. President Abraham Lincoln, unhappy with McClellan's general pattern of overcaution and his failure to pursue the retreating Lee, relieved McClellan of command in November. Nevertheless, the strategic accomplishment was a significant turning point in the war in favor of the Union due in large part to its political ramifications: the battle's result gave Lincoln the political confidence to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. This effectively discouraged the British and French governments from recognizing the Confederacy, as neither power wished to give the appearance of supporting slavery.

- ^ "Battle Detail - The Civil War (U.S. National Park Service)". Nps.gov. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ McPherson 2002, p. 155

- ^ "A Short Overview of the Battle of Antietam (U.S. National Park Service)". Nps.gov. Archived from the original on February 3, 2022. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ "Antietam Battle Facts and Summary | American Battlefield Trust". Battlefields.org. Archived from the original on October 13, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ Further information: Official Records, Series I, Volume XIX, Part 1, pp. 169–80 Archived July 10, 2012, at archive.today.

- ^ Further information: Official Records, Series I, Volume XIX, Part 1, pp. 803–10.

- ^ Further information: Reports of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, U. S. Army, commanding the Army of the Potomac, of operations August 14 – November 9 (Official Records, Series I, Volume XIX, Part 1, p. 67 Archived January 17, 2024, at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ a b Eicher, p. 363, cites 75,500 Union troops. Sears, p. 173, cites 75,000 Union troops, with an effective strength of 71,500, with 300 guns; on p. 296, he states that the 12,401 Union casualties were 25% of those who went into action and that McClellan committed "barely 50,000 infantry and artillerymen to the contest"; p. 389, he cites Confederate effective strength of "just over 38,000," including A.P. Hill's division, which arrived in the afternoon. Priest, p. 343, cites 87,164 men present in the Army of the Potomac, with 53,632 engaged, and 30,646 engaged in the Army of Northern Virginia. Luvaas and Nelson, p. 302, cite 87,100 Union engaged, 51,800 Confederate. Harsh, Sounding the Shallows, pp. 201–02, analyzes the historiography of the figures, and shows that Ezra A. Carman (a battlefield historian who influenced some of these sources) used "engaged" figures; the 38,000 excludes Pender's and Field's brigades, roughly half the artillery, and forces used to secure objectives behind the line.

- ^ Further information: Official Records, Series I, Volume XIX, Part 1, pp. 189–204 Archived July 8, 2012, at archive.today.

- ^ a b Union: 12,410 total (2,108 killed; 9,549 wounded; 753 captured/missing); Confederate: 10,316 total (1,546 killed; 7,752 wounded; 1,018 captured/missing) according to Sears, pp. 294–96; Cannan, p. 201. Confederate casualties are estimates because reported figures include undifferentiated casualties at South Mountain and Shepherdstown; Sears remarks that "there is no doubt that a good many of the 1,771 men listed as missing were in fact dead, buried uncounted in unmarked graves where they fell." McPherson, p. 129, gives ranges for the Confederate losses: 1,546–2,700 dead, 7,752–9,024 wounded. He states that more than 2,000 of the wounded on both sides died from their wounds. Priest, p. 343, reports 12,882 Union casualties (2,157 killed, 9,716 wounded, 1,009 missing or captured) and 11,530 Confederate (1,754 killed, 8,649 wounded, 1,127 missing or captured). Luvaas and Nelson, p. 302, cite Union casualties of 12,469 (2,010 killed, 9,416 wounded, 1,043 missing or captured) and 10,292 Confederate (1,567 killed, 8,725 wounded for September 14–20, plus approximately 2,000 missing or captured).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search