Back فريدريش فون فيزر Arabic فريدريش فون فيزر ARZ Friedrich von Wieser AST Fridrix fon Vizer Azerbaijani Фридрих фон Визер Bashkir Фрыдрых фон Візер Byelorussian Фрыдрых фон Візэр BE-X-OLD Фридрих фон Визер Bulgarian Friedrich von Wieser Catalan Friedrich von Wieser Czech

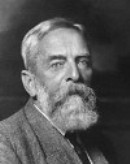

Friedrich von Wieser | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Friedrich Wieser 10 July 1851 |

| Died | 22 July 1926 (aged 75) |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Academic career | |

| School or tradition | Austrian School Lausanne School |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna (Dr. jur. 1872) |

| Influences | Carl Menger Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk |

Friedrich Freiherr von Wieser[1] (German: [ˈviːzɐ]; 10 July 1851 – 22 July 1926) was an early (so-called "first generation") economist of the Austrian School of economics. Born in Vienna, the son of Privy Councillor Leopold von Wieser, a high official in the war ministry, he first trained in sociology and law. In 1872, the year he took his degree, he encountered Austrian-school founder Carl Menger's Grundsätze and switched his interest to economic theory.[2] Wieser held posts at the universities of Vienna and Prague until succeeding Menger in Vienna in 1903, where along with his brother-in-law Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk he shaped the next generation of Austrian economists including Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek and Joseph Schumpeter in the late 1890s and early 20th century. He was the Austrian Minister of Commerce from August 30, 1917, to November 11, 1918.

Wieser is renowned for two main works, Natural Value,[3] which carefully details the alternative-cost doctrine and the theory of imputation; and his Social Economics (1914), an ambitious attempt to apply it to the real world. His explanation of marginal utility theory was decisive, at least terminologically. It was his term Grenznutzen (building on von Thünen's Grenzkosten) that developed into the standard term "marginal utility", not William Stanley Jevons's "final degree of utility" or Menger's "value". His use of the modifier "natural" indicates that he regarded value as a "natural category" that would pertain to any society, no matter what institutions of property had been established.[4]

The economic calculation debate started with his notion of the paramount importance of accurate calculation to economic efficiency. Above all, to him prices represented information about market conditions and are thus necessary for any sort of economic activity. Therefore, a socialist economy would require a price system in order to operate. He also stressed the importance of the entrepreneur to economic change, which he saw as being brought about by "the heroic intervention of individual men who appear as leaders toward new economic shores". This idea of leadership was later taken up by Joseph Schumpeter in his treatment of economic innovation.

Unlike most other Austrian School economists, Wieser rejected classical liberalism, writing that "freedom has to be superseded by a system of order". This vision and his general solution to the role of the individual in history is best expressed in his final book The Law of Power, a sociological examination of political order published in his last year of life.

- ^ Regarding personal names: Freiherr was a title before 1919, but now is regarded as part of the surname. It is translated as Baron. Before the August 1919 abolition of nobility as a legal class, titles preceded the full name when given (Graf Helmuth James von Moltke). Since 1919, these titles, along with any nobiliary prefix (von, zu, etc.), can be used, but are regarded as a dependent part of the surname, and thus come after any given names (Helmuth James Graf von Moltke). Titles and all dependent parts of surnames are ignored in alphabetical sorting. The feminine forms are Freifrau and Freiin.

- ^ Joseph A. Schumpeter, Ten Great Economists From Marx to Keynes, 1951, Appendix 2, p. 298, reprinted from The Economic Journal, vol. xxxvii, no. 146, June 1927.

- ^ Der Natürliche Werth, 1889; William Smart, ed. (1893). Natural Value. Translated by Christian A. Malcolm.

- ^ Mark Blaug, Great Economists Before Keynes, 1986, p. 280.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search