Back اقتصاد بدعي Arabic Alternativ iqtisadiyyat Azerbaijani Неортодоксална икономика Bulgarian কাল্পনিক অর্থনীতি Bengali/Bangla Heterodoxní ekonomie Czech Heterodoks økonomi Danish Heterodoxe Ökonomie German Economía heterodoxa Spanish اقتصاد دگراندیشانه Persian Orthodoxie et hétérodoxie en économie French

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

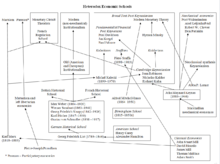

Heterodox economics is any economic thought or theory that contrasts with orthodox schools of economic thought, or that may be beyond neoclassical economics.[1][2] These include institutional, evolutionary, feminist,[3] social, post-Keynesian (not to be confused with New Keynesian),[2] ecological, Austrian, humanistic, complexity, Marxian, socialist, anarchist and modern monetary theory economics.[4]

Economics may be called orthodox or conventional economics by its critics.[5] Alternatively, mainstream economics deals with the "rationality–individualism–equilibrium nexus" and heterodox economics is more "radical" in dealing with the "institutions–history–social structure nexus".[6]

A 2008 review documented several prominent groups of heterodox economists since at least the 1990s as working together with a resulting increase in coherence across different constituents.[2] Along these lines, the International Confederation of Associations for Pluralism in Economics (ICAPE) does not define "heterodox economics" and has avoided defining its scope. ICAPE defines its mission as "promoting pluralism in economics."

In defining a common ground in the "critical commentary", one writer described fellow heterodox economists as trying to do three things: (1) identify shared ideas that generate a pattern of heterodox critique across topics and chapters of introductory macro texts; (2) give special attention to ideas that link methodological differences to policy differences; and (3) characterize the common ground in ways that permit distinct paradigms to develop common differences with textbook economics in different ways.[7]

One study suggests four key factors as important to the study of economics by self-identified heterodox economists: history, natural systems, uncertainty, and power.[8]

- ^ Fred E. Foldvary, ed., 1996. Beyond Neoclassical Economics: Heterodox Approaches to Economic Theory, Edward Elgar. Description and contents B&N.com links Archived 2013-12-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c Frederic S. Lee, 2008. "heterodox economics," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition, v. 4, pp. 2–65. Abstract. Archived 2016-12-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ In the order listed at JEL classification codes § B. History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches, JEL: B5 – Current Heterodox Approaches.

- ^ Lawson, T. (2005). "The nature of heterodox economics" (PDF). Cambridge Journal of Economics. 30 (4): 483–505. doi:10.1093/cje/bei093. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2010-03-30.

- ^ C. Barry, 1998. Political-economy: A comparative approach. Westport, CT: Praeger.[page needed]

- ^ John B. Davis (2006). "Heterodox Economics, the Fragmentation of the Mainstream, and Embedded Individual Analysis", in Future Directions in Heterodox Economics, p. 57 Archived 2022-12-06 at the Wayback Machine. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- ^ Cohn, Steve (2003). "Common Ground Critiques of Neoclassical Principles Texts". Post-Autistic Economics Review (18, article 3). Archived from the original on 2019-08-27. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ Mearman, Andrew (2011). "Who Do Heterodox Economists Think They Are?" American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 70(2): 480–510 Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search