Back Groot Migrasie (Afro-Amerikaners) Afrikaans الهجرة الكبرى (الأمريكيون الأفارقة) Arabic Flugten fra Sydstaterne Danish Great Migration (20. Jahrhundert) German Granda Migrado (afrikusonanoj) Esperanto Gran Migración Afroamericana Spanish Afro-amerikar Migrazio Handia Basque مهاجرت بزرگ Persian Grande migration afro-américaine French ההגירה הגדולה (אפרו-אמריקאים) HE

| Part of the Nadir of American race relations | |

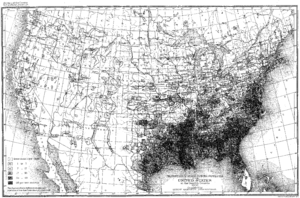

United States map of the Black American population from the 1900 U.S. census | |

| Date | 1910s–1970 |

|---|---|

| Location | United States |

| Also known as | Great Northward Migration Black Migration |

| Cause | Poor economic conditions More job opportunities in the North Racial segregation in the United States: |

| Participants | About 6,000,000 African Americans |

| Outcome | Demographic shifts across the U.S. Improved living conditions for African Americans |

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

The Great Migration, sometimes known as the Great Northward Migration or the Black Migration, was the movement of six million African Americans out of the rural Southern United States to the urban Northeast, Midwest, and West between 1910 and 1970.[1] It was substantially caused by poor economic and social conditions due to prevalent racial segregation and discrimination in the Southern states where Jim Crow laws were upheld.[2][3] In particular, continued lynchings motivated a portion of the migrants, as African Americans searched for social reprieve. The historic change brought by the migration was amplified because the migrants, for the most part, moved to the then-largest cities in the United States (New York City, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Cleveland, and Washington, D.C.) at a time when those cities had a central cultural, social, political, and economic influence over the United States; there, African-Americans established culturally influential communities of their own.[4] According to Isabel Wilkerson, despite the loss of leaving their homes in the South, and the barriers faced by the migrants in their new homes, the migration was an act of individual and collective agency, which changed the course of American history, a "declaration of independence" written by their actions.[5]

From the earliest U.S. population statistics in 1780 until 1910, more than 90% of the African American population lived in the American South,[6][7][8] making up the majority of the population in three Southern states, namely Louisiana (until about 1890[9]), South Carolina (until the 1920s[10]), and Mississippi (until the 1930s[11]). But by the end of the Great Migration, just over half of the African-American population lived in the South, while a little less than half lived in the North and West.[12] Moreover, the African-American population had become highly urbanized. In 1900, only one-fifth of African Americans in the South were living in urban areas.[13] By 1960, half of the African Americans in the South lived in urban areas,[13] and by 1970, more than 80% of African Americans nationwide lived in cities.[14] In 1991, Nicholas Lemann wrote:

The Great Migration was one of the largest and most rapid mass internal movements in history—perhaps the greatest not caused by the immediate threat of execution or starvation. In sheer numbers, it outranks the migration of any other ethnic group—Italians or Irish or Jews or Poles—to the United States. For Black people, the migration meant leaving what had always been their economic and social base in America and finding a new one.[15]

Some historians differentiate between a first Great Migration (1910–40), which saw about 1.6 million people move from mostly rural areas in the South to northern industrial cities, and a Second Great Migration (1940–70), which began after the Great Depression and brought at least five million people—including many townspeople with urban skills—to the North and West.[16]

Since the Civil Rights Movement, the trend has reversed, with more African-Americans moving to the South, albeit far more slowly. Dubbed the New Great Migration, these moves were generally spurred by the economic difficulties of cities in the Northeastern and Midwestern United States, growth of jobs in the "New South" and its lower cost of living, family and kinship ties, and lessening discrimination at the hands of White people.[17]

- ^ "The Great Migration (1910–1970)". May 20, 2021. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ "The Great Migration" (PDF). Smithsonian American Art Museum. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 27, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ Wilkerson, Isabel. "The Long-Lasting Legacy of the Great Migration". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ Gregory, James. "Black Metropolis". America's Great Migrations Projects. University of Washington. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2021. (with excepts from, Gregory, James. The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America, Chapter 4: "Black Metropolis" (University of North Carolina Press, 2005)

- ^ Wilkerson, Isabel (September 2016). "The Long-Lasting Legacy of the Great Migration". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ Purvis, Thomas L. (1999). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Colonial America to 1763. New York: Facts on File. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-0816025275.

- ^ "Colonial and Pre-Federal Statistics" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. p. 1168. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 29, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ Gibson, Campbell; Jung, Kay (September 2002). Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and by Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States (PDF) (Report). Population Division Working Papers. Vol. 56. United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 14, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ "Table 33. Louisiana – Race and Hispanic Origin: 1810 to 1990" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Race and Hispanic Origin for States" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2014. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ "Table 39. Mississippi – Race and Hispanic Origin: 1800 to 1990" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2010.

- ^ "The Second Great Migration". The African American Migration Experience. New York Public Library. Archived from the original on March 12, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Taeuber, Karl E.; Taeuber, Alma F. (1966), "The Negro Population in the United States", in Davis, John P. (ed.), The American Negro Reference Book, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, p. 122

- ^ "The Second Great Migration", The African American Migration Experience, New York Public Library, archived from the original on March 12, 2020, retrieved March 23, 2016

- ^ Lemann, Nicholas (1991). The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 6. ISBN 0394560043.

- ^ Frey, William H. (May 2004). "The New Great Migration: Black Americans' Return to the South, 1965–2000". The Brookings Institution. pp. 1–3. Archived from the original on June 17, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2008.

- ^ Reniqua Allen (July 8, 2017). "Racism Is Everywhere, So Why Not Move South?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search