Back حرب الكونغو الأولى Arabic بیرینجی کونقو ساواشی AZB Першая кангалезская вайна Byelorussian Brezel kentañ Kongo Breton První válka v Kongu Czech Erster Kongokrieg German Unua Konga Milito Esperanto Primera guerra del Congo Spanish Kongoko Lehen Gerra Basque جنگ نخست کنگو Persian

| First Congo War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide and the spillover of the Burundian Civil War and the Second Sudanese Civil War | |||||||

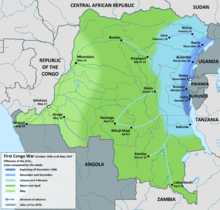

Map showing the AFDL offensive | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Mai-Mai[a] |

Mai-Mai[a] | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Zaire: c. 50,000[b] Interahamwe: 40,000–100,000 total[22] UNITA: c. 1,000[22]–2,000[6] |

AFDL: 57,000[23]

Angola: 3,000+[25] Eritrea: 1 battalion[26] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

10,000–15,000 killed 10,000 defected[25] thousands surrender | 3,000–5,000 killed | ||||||

|

222,000 refugees missing[27] Total: 250,000 dead[28] | |||||||

The First Congo War[c] (1996–1997), also nicknamed Africa's First World War,[29] was a civil war and international military conflict which took place mostly in Zaire (which was renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the process), with major spillovers into Sudan and Uganda. The conflict culminated in a foreign invasion that replaced Zairean president Mobutu Sese Seko with the rebel leader Laurent-Désiré Kabila. Kabila's unstable government subsequently came into conflict with his allies, setting the stage for the Second Congo War in 1998–2003.

Following years of internal strife, dictatorship and economic decline, Zaire was a dying state by 1996. The eastern parts of the country had been destabilized due to the Rwandan genocide which had perforated its borders, as well as long-lasting regional conflicts and resentments left unresolved since the Congo Crisis. In many areas state authority had in all but name collapsed, with infighting militias, warlords, and rebel groups (some sympathetic to the government, others openly hostile) wielding effective power.[30][31] The population of Zaire had become restless and resentful of the inept and corrupt regime; the Zairean Armed Forces were in a catastrophic condition.[32][21] Mobutu, who had become terminally ill, was no longer able to keep the different factions in the government under control, making their loyalty questionable. Furthermore, the end of the Cold War meant that Mobutu's strong anti-communist stance was no longer sufficient to justify the political and financial support he had received from the capitalist powers – his regime, therefore, was essentially politically and financially bankrupt.[33][20]

The situation finally escalated when Rwanda invaded Zaire in 1996 to defeat a number of rebel groups which had found refuge in the country. This invasion quickly escalated, as more states (including Uganda, Burundi, Angola, and Eritrea) joined the invasion, while a Congolese alliance of anti-Mobutu rebels was assembled.[30] Though the Zairean government attempted to put up an effective resistance, and was supported by allied militias as well as Sudan, Mobutu's regime collapsed in a matter of months.[34] Despite the war's short duration, it was marked by widespread destruction and extensive ethnic violence, with hundreds of thousands killed in the fighting and accompanying pogroms.[35]

A new government was installed, and Zaire was renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but the termination of the Mobutu regime brought little political change, and Kabila found himself uneasy in the position of a proxy of his former benefactors. To avert a coup, Kabila expelled all Rwandan, Ugandan and Burundian military units from the Congo, and moved to build a coalition including Namibian, Angolan, Zimbabwean and Zambian forces, soon encompassing a string of African nations from Libya to South Africa, although their support varied.[36] The tripartite coalition responded with a second invasion of the east, largely through proxy groups. These actions constituted the catalyst for the Second Congo War the following year, although some experts prefer to view the two conflicts as one continuous war whose aftereffects continue today.[37][38]

- ^ a b Prunier (2004), pp. 376–377.

- ^ Toïngar, Ésaïe (2014). Idriss Deby and the Darfur Conflict. p. 119.

In 1996, President Mobutu of Zaire requested that mercenaries be sent from Chad to help defend his government from rebel forces led by Lauren Desiré Kabila. ... When a number of the troops were ambushed by Kabila and killed in defense of Mobutu's government, Mobutu paid Déby a fee in honor of their service.

- ^ Prunier (2009), pp. 116–118.

- ^ Duke, Lynne (20 May 1997). "Congo Begins Process of Rebuilding Nation". The Washington Post. p. A10. Archived from the original on 24 February 2011.

Guerrillas of Angola's former rebel movement UNITA, long supported by Mobutu in an unsuccessful war against Angola's government, also fought for Mobutu against Kabila's forces.

- ^ a b Prunier (2004), pp. 375–377.

- ^ a b Reyntjens 2009, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

francewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

CARwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Reyntjens 2009, pp. 112.

- ^ Prunier (2009), pp. 117, 130, 143.

- ^ Prunier (2009), p. 130.

- ^ Prunier (2009), p. 143.

- ^ Prunier (2004), pp. 375–376.

- ^ a b Duke, Lynne (15 April 1997). "Passive Protest Stops Zaire's Capital Cold". The Washington Post. p. A14. Archived from the original on 24 February 2011.

Kabila's forces – which are indeed backed by Rwanda, Angola, Uganda and Burundi, diplomats say – are slowly advancing toward the capital from the eastern half of the country, where they have captured all the regions that produce Zaire's diamonds, gold, copper and cobalt.

- ^ Plaut (2016), pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b "Consensual Democracy" in Post-genocide Rwanda. International Crisis Group. 2001. p. 8.

In that first struggle in the Congo, Rwanda, allied with Uganda, Angola, Zimbabwe, South Africa and Burundi, had brought Laurent Désiré Kabila to power in Kinshasa

- ^ Reyntjens 2009, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Usanov, Artur (2013). Coltan, Congo and Conflict. Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. p. 36.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

nyererewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Prunier (2009), pp. 118, 126–127.

- ^ a b c Prunier (2009), p. 128.

- ^ a b c Thom, William G. (1999). "Congo-Zaire's 1996–97 Civil War in the Context of Evolving Patterns of Military Conflict in Africa in the Era of Independence". Journal of Conflict Studies. 19 (2).

- ^ a b This number was self-declared and was not independently verified. Johnson, Dominic: Kongo — Kriege, Korruption und die Kunst des Überlebens, Brandes & Apsel, Frankfurt am Main, 2. Auflage 2009 ISBN 978-3-86099-743-7

- ^ Prunier (2004), p. 251.

- ^ a b c Abbott (2014), p. 35.

- ^ Plaut (2016), p. 55.

- ^ CDI: The Center for Defense Information, The Defense Monitor, "The World At War: January 1, 1998".

- ^ "Democratic Republic of Congo: War against unarmed civilians". Amnesty International. AFR 62/036/1998. 23 November 1998.

- ^ Prunier (2009), p. 72.

- ^ a b Abbott (2014), pp. 33–35.

- ^ Prunier (2009), pp. 77, 83.

- ^ Abbott (2014), pp. 23–24, 33.

- ^ Abbott (2014), pp. 23–24, 33–35.

- ^ Abbott (2014), pp. 34–35.

- ^ Prunier (2009), pp. 143–148.

- ^ Abbott (2014), pp. 36–39.

- ^ Reyntjens 2009, p. 194.

- ^ "DISARMAMENT: SADC Moves into Unknown Territory". 19 August 1998. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search