Back Зыхәны Abkhazian Адыгэ Хэку ADY شركيسيا Arabic شركسيا ARZ Circasia AST Черкесия AV Çərkəzistan Azerbaijani সার্কাসিয়া Bengali/Bangla Sirkasia Breton Circàssia Catalan

Circassia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 7th century–1864 | |||||||||

| Motto: Псэм ипэ напэ (Adyghe) Psem ipe nape ("Honour before life") | |||||||||

Area marked Circassia | |||||||||

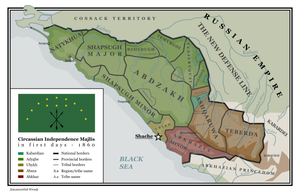

Revised administrative divisions of Circassia in 1860 according to a decree issued by the Circassian Parliament | |||||||||

| Residence of leader (Capital) |

43°35′07″N 39°43′13″E / 43.58528°N 39.72028°E | ||||||||

| Largest town | Shache (Sochi) | ||||||||

| Official languages | Circassian languages | ||||||||

| Other languages | |||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Circassian | ||||||||

| Government | Union of Regional Councils[1][2] | ||||||||

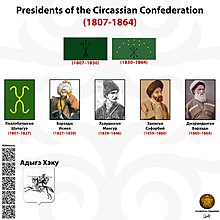

• Leader of Western Circassia c. 100s c. 400s c. 500s 668–960 c. 960s–1000s c. 1000s–1022 c. 1200s c. 1200s–1237 1237–1239 c. 1330s c. late 1300s c. 1427–1453 c. 1453-c. 1470s c. 1470s-? c. 1530s–1542 1807–1827 1827–1839 1839–1846 1849–1859 1859–1860 1861–1864 | List: Stakhemfaqu (Stachemfak) Dawiy Bakhsan Dawiqo Khazar rule Hapach Rededya Abdunkhan Tukar Tukbash Verzacht Berezok Inal the Great Belzebuk Petrezok Kansavuk Shuwpagwe Qalawebateqo Ismail Berzeg Hawduqo Mansur Muhammad Amin Sefer Bey Zanuqo Qerandiqo Berzeg | ||||||||

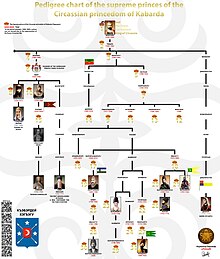

• Prince of Eastern Circassia c. 1427–1453 1453–c. 1490 c. 1490–c. 1500 c. 1500–c. 1525 c. 1525–c. 1540 c. 1540–1554 1554–1571 1571–1578 1578–1589 1589–1609 1609–1616 1616–1624 1624–1654 1654–1672 1672–1695 1695–1710 1710–1721 1721–1732 1732–1737 1737–1746 1746–1749 1749–1762 1762–1773 1773–1785 1785–1788 1788–1809 1809 1810–1822 | List: Inal the Great Tabulda Inarmas Beslan Idar Kaytuk I Temruk Shiapshuk Kambulat Kaytuk II Sholokh Kudenet Aleguko Atajuq I Misost Atajuq II Kurgoqo Atajuq III Misewestiqo Islambek Tatarkhan Qeytuqo Aslanbech Batoko Bamat Muhammad Qasey Atajuq Jankhot Misost II Bematiqwa Atajuq III Atajuq IV Jankhot II Qushuq | ||||||||

| Confederation Leaders | |||||||||

| Legislature | Lepq Zefes Parliament of Independence (1860-1864) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | c. 7th century | ||||||||

| 1763–1864 | |||||||||

• Disestablished | 1864 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• Total | 82,000 km2 (32,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• Estimate | 1,625,000 (pre-Circassian genocide) 86,655 (post-Circassian genocide)[3][4][5][6][7] | ||||||||

| Currency | No official currency. Ottoman coins served as de facto currency | ||||||||

Circassia in 1450 during the reign of Inal the Great | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Russia Georgia [a] | ||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| Circassians Адыгэхэр |

|---|

List of notable Circassians Circassian genocide |

| Circassian diaspora |

| Circassian tribes |

|

Surviving Destroyed or barely existing |

| Religion |

|

Religion in Circassia |

| Languages and dialects |

|

| History |

|

Show |

| Culture |

Circassia[b] (/sɜːrˈkæʃə/ sir-KASH-ə), also known as Zichia,[8][9] was a country and a historical region in the North Caucasus, along the northeast shore of the Black Sea.[10][11] It was conquered by the Russian Empire during the Russo-Circassian War (1763–1864), after which 90% of the Circassian people were either exiled from the region or massacred in the Circassian genocide.[12][13][14][15][16]

In the Medieval Era, Circassia was nominally ruled by the elected Grand Prince but individual principalities and tribes were autonomous. In the 18th-19th centuries, a central government began to form. The Circassians also dominated the north of the Kuban river in the early medieval and ancient times, but with the raids of the Mongol Empire, Golden Horde and the Crimean Khanate, they were withdrawn south of the Kuban, and their reduced borders stretched from the Taman Peninsula to North Ossetia. During the Medieval Era, Circassian lords subjugated and vassalized the neighboring Karachay-Balkars and Ossetians.[17] The term Circassia is also used as the collective name of Circassian states established on Circassian territory, such as Zichia.[8][9][18]

Legally and internationally, the Treaty of Belgrade of 1739 between Austria and Turkey provided for the recognition of the independence of Eastern Circassia (Kabarda). Both the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire recognized it, and the great powers at the time witnessed the treaty. The Congress of Vienna held in the period between 1814 and 1815 also stipulated the recognition of the independence of Circassia. In 1837, Circassian leaders sent letters to European countries requesting legal recognition. Following this, the United Kingdom recognized Circassia.[19][20] However, during the Russian-Circassian War, the Russian Empire did not recognize Circassia as an independent region, and treated it as Russian land under rebel occupation, despite having no control or ownership over the region.[21] Russian generals referred to the Circassians not by their ethnic name, but as "mountaineers", "bandits", and "mountain scum".[21][22]

Although Circassia is the original homeland of the Circassian people, today most Circassians live in exile, following the Circassian genocide.[23][24][25][26]

- ^ The Circassian state was a federal state consisting of four levels of government: Village council (чылэ хасэ, made up of village elders), district council (made up of representatives from 7 neighboring village councils), regional council (шъолъыр хасэ, made up from neighboring district councils), people's council (лъэпкъ зэфэс, where every council had a representative). There wasn't a central ruler until the 1800s, and the leader was symbolic in nature. A central government existed during the mid to late 1800s.

- ^ "Dünyayı yıkımdan kurtaracak olan şey : Çerkes tipi hükümet sistemi". Ghuaze. 5 November 2022.

- ^ “Алфавитный список народов, обитающих в Российской Империи” Archived 5 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Демоскоп Weekly, № 187 - 188, 24 января - 6 февраля 2005 ve buradan alınma olarak: Papşu, Murat. Rusya İmparatorluğu’nda Yaşayan Halkların Alfabetik Listesinde Kafkasyalılar Archived 18 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Genel Komite, HDP (2014). "The Circassian Genocide". www.hdp.org.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Richmond, Walter (2013-04-09). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- ^ Geçmişten günümüze Kafkasların trajedisi: uluslararası konferans, 21 Mayıs 2005 (in Turkish). Kafkas Vakfı Yayınları. 2006. ISBN 978-975-00909-0-5.

- ^ "Tarihte Kafkasya - ismail berkok - Nadir Kitap". NadirKitap (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ a b де Галонифонтибус И., 1404, II. Черкесия (Гл. 9).

- ^ a b Хотко С. К. Садзы-джигеты.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 380–381.

- ^ Evliya Çelebi, Seyahatnâme, II, 61-70; VII, 265-295

- ^ Genel Komite, HDP (2014). "The Circassian Genocide". www.hdp.org.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Richmond, Walter (2013-04-09). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- ^ Geçmişten günümüze Kafkasların trajedisi: uluslararası konferans, 21 Mayıs 2005 (in Turkish). Kafkas Vakfı Yayınları. 2006. ISBN 978-975-00909-0-5.

- ^ "UNPO: The Circassian Genocide". unpo.org. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ "Tarihte Kafkasya - ismail berkok | Nadir Kitap". NadirKitap (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Bilge, Sadık Müfit. "Çerkezler: Kafkaslar'da yaşayan halklardan biri". TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Retrieved 2021-06-24.

- ^ де Галонифонтибус И., 1404, I. Таты и готы. Великая Татария: Кумания, Хазария и другие. Народы Кавказа (Гл. 8), Прим. 56..

- ^ Bashqawi, Adel (15 September 2017). Circassia: Born to Be Free. Xlibris. ISBN 978-1543447644.

- ^ Jaimoukha, Amjad. The Circassians: A Handbook.

- ^ a b Richmond, Walter (9 April 2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- ^ Capobianco, Michael (13 October 2012). "Blood on the Shore: The Circassian Genocide". Caucasus Forum.

- ^ Richmond, Walter (2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0813560694.

- ^ Zhemukhov, Sufian (2008). "Circassian World Responses to the New Challenges" (PDF). PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 54: 2. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ Danver, Steven L. (2015). Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues. Routledge. p. 528. ISBN 978-1317464006.

- ^ "single | The Jamestown Foundation". Jamestown. Jamestown.org. 7 May 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search