Back تاريخية الكتاب المقدس Arabic Historicita Bible Czech Historicidad de la Biblia Spanish Raamatun historiallisuus Finnish ההיסטוריות של התנ"ך HE Historisitas Alkitab ID Storicità della Bibbia Italian 역사적 성경해석 Korean Historiciteit van de Bijbel Dutch Historicidade da Bíblia Portuguese

| Part of a series on the |

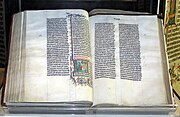

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

The historicity of the Bible is the question of the Bible's relationship to history—covering not just the Bible's acceptability as history but also the ability to understand the literary forms of biblical narrative.[1] One can extend biblical historicity to the evaluation of whether or not the Christian New Testament is an accurate record of the historical Jesus and of the Apostolic Age. This tends to vary depending upon the opinion of the scholar.

When studying the books of the Bible, scholars examine the historical context of passages, the importance ascribed to events by the authors, and the contrast between the descriptions of these events and other historical evidence. Being a collaborative work composed and redacted over the course of several centuries,[2] the historicity of the Bible is not consistent throughout the entirety of its contents.

According to theologian Thomas L. Thompson, a representative of the Copenhagen School, also known as "biblical minimalism", the archaeological record lends sparse and indirect evidence for the Old Testament's narratives as history.[3][4][5][6][7] Others, like archaeologist William G. Dever, felt that biblical archaeology has both confirmed and challenged the Old Testament stories.[8] While Dever has criticized the Copenhagen School for its more radical approach, he is far from being a biblical literalist, and thinks that the purpose of biblical archaeology is not to simply support or discredit the biblical narrative, but to be a field of study in its own right.[9][10]

Some scholars argue that the Bible is national history, with an "imaginative entertainment factor that proceeds from artistic expression" or a "midrash" on history.[11][12]

- ^ Thompson 2014, p. 164.

- ^ Greifenhagen, Franz V. (2003). Egypt on the Pentateuch's Ideological Map. Bloomsbury. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-567-39136-0.

- ^ Enns 2013: "Biblical archaeology has helped us understand a lot about the world of the Bible and clarified a considerable amount of what we find in the Bible. But the archaeological record has not been friendly for one vital issue, Israel's origins: the period of slavery in Egypt, the mass departure of Israelite slaves from Egypt, and the violent conquest of the land of Canaan by the Israelites. The strong consensus is that there is at best sparse indirect evidence for these biblical episodes, and for the conquest there is considerable evidence against it."

- ^

Davies, Philip (April 2010). "Beyond Labels: What Comes Next?". The Bible and Interpretation. Retrieved 2016-05-31.

It has been accepted for decades that the Bible is not in principle either historically reliable or unreliable, but both: it contains both memories of real events and also fictions.

- ^ Golden 2009, p. 275: "So although much of the archaeological evidence demonstrates that the Hebrew Bible cannot in most cases be taken literally, many of the people, places and things probably did exist at some time or another."

- ^ Grabbe 2007: "The fact is that we are all minimalists—at least, when it comes to the patriarchal period and the settlement. When I began my PhD studies more than three decades ago in the USA, the 'substantial historicity' of the patriarchs was widely accepted as was the unified conquest of the land. These days it is quite difficult to find anyone who takes this view.

"In fact, until recently I could find no 'maximalist' history of Israel since Wellhausen. ... In fact, though, 'maximalist' has been widely defined as someone who accepts the biblical text unless it can be proven wrong. If so, very few are willing to operate like this, not even John Bright (1980) whose history is not a maximalist one according to the definition just given." - ^ Nur Masalha (20 October 2014). The Zionist Bible: Biblical Precedent, Colonialism and the Erasure of Memory. Routledge. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-317-54465-4.

critical archaeology—which has become an independent professional discipline with its own conclusions and its observations—presents us with a picture of a reality of ancient Palestine completely different from the one that is described in the Hebrew Bible; Holy Land archaeology is no longer using the Hebrew Bible as a reference point or an historical source; the traditional biblical archaeology is no longer the ruling paradigm in Holy Land archaeology; for the critical archaeologists the Bible is read like other ancient texts: as literature which may contain historical information (Herzog, 2001: 72–93; 1999: 6–8).

- ^ Dever, William G. (March–April 2006). "The Western Cultural Tradition Is at Risk". Biblical Archaeology Review. 32 (2): 26 & 76. "Archaeology as it is practiced today must be able to challenge, as well as confirm, the Bible stories. Some things described there really did happen, but others did not. The biblical narratives about Abraham, Moses, Joshua and Solomon probably reflect some historical memories of people and places, but the "larger than life" portraits of the Bible are unrealistic and contradicted by the archaeological evidence."

- ^ William G. Dever (1992). "Archeology". In David Noel Freedman (ed.). The Anchor Bible dictionary. Doubleday. p. 358. ISBN 978-0-385-19361-0.

- ^ J.K. Hoffmeier (2015). Thomas E. Levy; Thomas Schneider; William H.C. Propp (eds.). Israel's Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective: Text, Archaeology, Culture, and Geoscience. Springer. p. 200. ISBN 978-3-319-04768-3.

- ^ Dearman, J. Andrew (2018). Reading Hebrew Bible Narratives. Oxford University Press. pp. 113–129. ISBN 9780190246525.

- ^ Hendel, Ronald (2005). Remembering Abraham: Culture, Memory, and History in the Hebrew Bible. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–30. ISBN 9780199784622.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search