Back التأليف الموسوي Arabic Autoría mosaica Spanish Auctoritas Mosaica Latin Autori ai cărților lui Moise Romanian

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

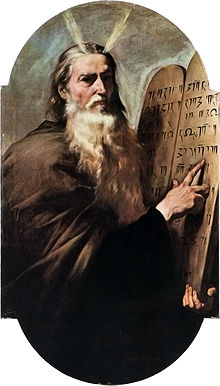

Mosaic authorship is the Judeo-Christian tradition that the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, were dictated by God to Moses.[1] The tradition probably began with the legalistic code of the Book of Deuteronomy and was then gradually extended until Moses, as the central character, came to be regarded not just as the mediator of law but as author of both laws and narrative.[2][3]

The books of the Torah do not name any author, as authorship was not considered important by the society that produced them,[4][5] and it was only after Jews came into intense contact with author-centric Hellenistic culture in the late Second Temple period that the rabbis began to find authors for their scriptures.[4] By the 1st century CE, it was already common practice to refer to the five as the "Law of Moses", but the first unequivocal expression of the idea that this meant authorship appears in the Babylonian Talmud, an encyclopedia of Jewish tradition and scholarship composed between 200 and 500 CE.[6][7] There, the rabbis noticed and addressed such issues as how Moses had received the divine revelation,[8] how it was curated and transmitted to later generations, and how difficult passages such as the last verses of Deuteronomy, which describe his death, were to be explained.[9] This culminated in the 8th of Maimonides' 13 Principles of Faith, establishing belief in Mosaic authorship as an article of Jewish belief.[10]

Mosaic authorship of the Torah was unquestioned by both Jews and Christians until the European Enlightenment, when the systematic study of the five books led the majority of scholars to conclude that they are the product of multiple authors throughout many centuries.[11] Despite this, the role of Moses is an article of faith in traditional Jewish circles and for some Christian Evangelical scholars, for whom it remains crucial to their understanding of the unity and authority of the Bible.[12]

- ^ Robinson 2008, p. 97.

- ^ McEntire 2008, p. 11.

- ^ Collins 2014, p. 50.

- ^ a b Schniedewind 2005, p. 6–7.

- ^ Carr 2000, p. 492.

- ^ Robinson 2008, p. 98.

- ^ McEntire 2008, p. 10.

- ^ Heschel 2005, p. 539–540.

- ^ Robinson 2008, p. 97–98.

- ^ Levenson 1993, p. 63.

- ^ McDermott 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Tenney 2010, p. unpaginated.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search